My walking is of two kinds: one, straight on end to a definite goal at a round pace; one, objectless, loitering, and purely vagabond. In the latter state, no gipsy on earth is a greater vagabond than myself; it is so natural to me, and strong with me, that I think I must be the descendant, at no great distance, of some irreclaimable tramp.

Charles Dickens, The Uncommercial Traveller

I live in the heart of Charles Dickens territory. Rochester and the Medway towns are where Dickens grew up, where he returned to in prosperous middle age, and provide umpteen locations for scenes in his novels. Rochester revels in the association, with two annual festivals in which numerous vaguely Dickensian events are put on and many people dress up as Dickensian characters. The high street businesses alone bear witness to the Dickensian connection: they include Tiny Tim’s Tearooms, Fezziwig’s, Mr Tope’s, Ebenezer’s, Pips of Rochester, Sweet Expectations, and the inspired A Taste of Two Cities. In days past we have had Hard Times the antique shop, and – believe it or not – the Havisham Wedding Centre, which perhaps not surprisingly went out of business.

What with Dickens’ bicentenary last year I thought I needed to do a bit more to acknowledge my Dickens surroundings, and decided that I would undertake a series of Dickens walks. Charles Dickens was a prodigious walker. Whether on his night walks through London, or tramping through the Kent countryside, Dickens clocked up a huge number of miles on foot. He is estimated to have walked twelve miles per day – Peter Ackroyd, in his biography of Dickens, says that he habitually walked twelve miles in two-and-a-half hours, with just a five-minute break. That’s 4.8mph, which is at the upper limit of human walking speed (Dickens himself estimates that his average walking speech was 4 mph), and Dickens maintained this in all weathers. Dickens understood his passion for walking to be prodigious. In The Uncommercial Traveller, he writes:

So much of my travelling is done on foot, that if I cherished betting propensities, I should probably be found registered in sporting newspapers under some such title as the Elastic Novice, challenging all eleven stone mankind to competition in walking. My last special feat was turning out of bed at two, after a hard day, pedestrian and otherwise, and walking thirty miles into the country to breakfast.

Pedestrianism, or competitive walking, was popular in nineteenth-century Britain. Dickens made references to the renowned walker Captain Robert Barclay in his writings, and probably could have challenged the leading athletes of the time in endurance races. The thirty-mile feat probably refers to a famous walk he made when he escaped tensions at his London home, Tavistock House, and walked through the night to his Kent home, Gad’s Hill.

Gad’s Hill is a forty-minute walk out of Rochester (or thirty minutes, if you were Dickens). The journey has probably lost a little of its poetry since the 1850s. Crossing Rochester bridge, you process up the hill through the unremittingly unpoetic Strood, then walk along the Gravesend Road, or the A226, then cross the busy A289 before you walk up Gad’s Hill itself to the relative quietness of the small town of Higham. Dickens made this journey frequently, and it is easy to imagine the less athletically inclined members of his family and visitors sighing as they were busied along on another visit to the main town and back, struggling to keep up as the great man strode ahead.

However, Dickens mostly walked alone. He did so because walking time was thinking time, or perhaps more accurately dreaming time. Whether walking purposefully or in vagabond style, as he classifies his walking habits in The Uncommercial Traveller, Dickens proceeded in a reverie, acutely attuned to the significance of his surroundings. G.K. Chesterton, in Charles Dickens: A Critical Study (1906), makes this remarkable judgment of the connection between Dickens’ writing and walking:

Herein is the whole secret of that eerie realism with which Dickens could always vitalize some dark or dull corner of London. There are details in the Dickens descriptions — a window, or a railing, or the keyhole of a door — which he endows with demoniac life. The things seem more actual than things really are. Indeed, that degree of realism does not exist in reality: it is the unbearable realism of a dream. And this kind of realism can only be gained by walking dreamily in a place; it cannot be gained by walking observantly.

It takes some sort of critical genius to understand Dickens’ walking not to be observant in the conventional sense, but an act of dreaming. He walked not to see things but to get the sense of them. Chesterton’s subtle observation is discussed in Rebecca Solnit’s excellent Wanderlust: A History of Walking (2000). For Solnit, Dickens walked for multiple reasons: physical, metaphysical, investigative, vagabond. “I am both a town traveller and a country traveller, and am always on the road” he writes in The Uncommercial Traveller, his series of essays linked by the idea of walking, and there is there the sense of Dickens having always to walk, so that he was travelling in his mind wherever he might be, and being released into the act of walking became a necessary expression of his mind’s direction. And to understand Dickens we need to walk likewise, even if like his family and friends we may struggle to keep up.

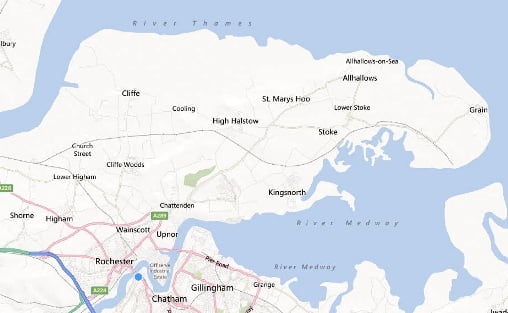

I am more of an ambler than a walker, so my most recent Dickens-inspired walk took more than double the time the man himself would have expended. I walked from Rochester to Higham, then across the Hoo peninsula to Cooling, High Halstow, then down to Upnor and finally back to Rochester once more. The Hoo Peninsula is a sparsely-populated area of north Kent that juts out into the Thames estuary. It is familiar to Dickens’ readers as the marshland setting for the opening chapters of Great Expectations, and much of the area still retains that plain, bleak quality, particularly around the Northwood Hill National Nature Reserve. There are few houses, and much farmland, while heavy industry in the form of power stations, gravel works, and a container terminal occupies the edges, particularly around Cliffe and the Isle of Grain. It would have been stark territory indeed when Dickens walked.

I went from Higham a couple of miles north to St Mary’s church, Dickens’ parish church (I sensed how family members must have groaned on a Sunday and wished that either they or the church could have been a little nearer). The road gives up at this point, and I proceeded across fields, along little-used railways lines and past water-filled gravel pits, past Cliffe and onwards to Cooling, which was the main purpose of my journey. Cooling is a small strip of a village with the ruins of a privately-owned castle and St James’ church, which was a favourite Dickens picnic location (more groans from the footsore family). It’s an ancient, now disused (but handsomely maintained) church with a 13th century font and some 14th century pews. But its most famous feature is found in the graveyard – thirteen gravestones of the children of two families, known now as ‘Pip’s graves’.

In Great Expectations, Pip describes seeing:

… five little stone lozenges, each about a foot and a half long, which were arranged in a neat row beside their grave, and were sacred to the memory of five little brothers of mine, — who gave up trying to get a living, exceedingly early in that universal struggle …

Famously Dickens reduced the number from thirteen to five, so as not to stretch the credibility of his readers too far. But the thirteen gravestones are there in a row, even if they do derive from two families rather than one. The names are no longer readable, but they are of the Baker and Comport families, none of whom lived beyond the age of seventeen months, having died between 1771 and 1779. They may all have died of malaria (ague), no great surprise in a marshland area. I was there on a bright summer’s day, but one can readily imagine the scene in the greys of winter with a sharp wind coming in off the North Sea to feel that overpowering sense of time, place and consequence – “the unbearable realism of a dream” – that is the cornerstone of Dickens’ art.

To be at St James’ church is to feel that you are on the edge of nowhere. Though there were signs of human habitation, there were no humans, bar myself. The church, no longer functioning as a church, pays witness to lives lived on the margin, people whose lives came and went unnoticed. It is a place of minimal expectations. Yet those lives went on, and there is a powerful sense of a life on the margins being a life for all that, something which imbues the UK’s many used and disused (or redundant) churches, which makes their continued preservation so important. It is not the chancels, naves and pews that matter, though they have their value. It is the lives past that revolved around such buildings that are important. They make things more actual than things really are; they turn plain reality into reverie, and connect our lives to stories – such as Pip’s. Something of this Charles Dickens saw in Cooling, as he walked by, paused awhile, and then walked on.

I headed on to High Halstow, turned right down Dux Court Road, then past Deangate, Lower Upnor, Upnor, Strood and home again. And then wrote this.

Links:

- A Flickr photo gallery of my Rochester-Cooling-Rochester journey can be seen here

- There are many guided Dickens walks out there – here’s one for London and one for Rochester

- The Hoo Pensinsula has been identified as a possible location for a new London airport – Stop Estuary Airport is campaigning against this

- The Churches Conservation Trust is the national charity for the protection of redundant churches – www.visitchurches.org.uk

Thank you for the excellent overview of Dickens as walker and the photos of the region. Much appreciated.

Thank you. It’s good to walk with a sense of history.

Luke

I recently visited St James’ church and Gads Hill Place with the Dickens Fellowship. I found your article interesting, enjoyable and inspiring.

Dr Samuel Johnson was a walker too and sometimes walked from Lichfield to Birmingham and back, which is approx 30 miles. He found this helped him overcome his melancholy or ‘black dog’.

Thank you. I’m glad you found the article interesting, and I hope you enjoyed your visit to Gads Hill and St James’ church. It is certainly a privilege to live in an area so rich in Dickensian associations.

I would like to make that Johnson walk one day. 30 miles is good for defeating any black dog.

Hello

Just a question really,where do I go and who do I talk to if I want to become a Dickens tour guide? I’ve rang a half a dozen people and organisations but not one knew.

Thank you

I don’t really know, but the Visitor Information Centre in Rochester ought to be able to advise:

95 High Street

Rochester

Kent ME1 1LX

01634 338141

visitor.centre@medway.gov.uk

http://www.visitmedway.org/

Thank you kind Sir for a thoughtful, interesting, informative article. I have been reading Wilkie Collins lately so of course Dickens history was on my mind, and your very nice article here was most enjoyable and educational. Thanks again!

Thank you. Glad you enjoyed it.

Great article. Is it possible for you to map the famous nighttime walk from Tavistock House to Gad’s Hill? I would like to try it next time I’m in London. Thank you.

Thank you. I have it in mind to do that walk one day (and of course it would have to be done at night), though the route is so built-up that it would probably not be that instructive, or maybe even possible. I don’t think the exact route is recorded, but presumably he roughly followed the Watling Street route.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Watling_Street

Acknowledgment has been made to this post, in particular its mention of the Havisham Wedding Centre, in Nick Hornby’s book Dickens and Prince: A Particular Kind of Genius (2022)

I’m a latecomer to this post, and would just like to say how much I enjoyed it. I particularly value the way you have ventured into the psychological and emotional hinterland of Dickens’s walking mania. Thank you!

Thank you so much. It’s good to see that this old post is still getting readers. Living here and walking here, you do get the sense that you are progressing through the man’s mind.