Highlights from NRK’s ten-hour Nordlandsbanen train journey programme

In December the Norwegian broadcaster NRK put on a ten-hour transmission of a train journey. Filmed from the front of a train cab travelling along the Nordlandsbanen line between Trondheim and Bodø (a distance of 438 miles), the programme gained one million viewers, or a fifth of the population. What was shown was actually a composite of four journeys, filmed over each of the four seasons. The full journey can be viewed on NRK’s special Nordlandbanen page, which offers the original transmission, each of the four journeys from spring, summer, autumn and winter, and a version which shows the four seasons in parallel on four quarters of the screen.

NRK has enjoyed a succession of hits with such journey programmes, or ‘slow TV’. The first was a rail journey along the Bergensbanen between Bergen and Oslo broadcast in 2009, with its real-time transmission of a 2011 Hurtigruten coastal boat journey made between Bergen to Kirkenes over six days – probably the world’s longest documentary – being a particular success, with 2.6 million people watching on TV and online along the way.

Such events are arguably film in its purest form. You turn on the camera, and let the world go by. No editing, no cheating with the flow of time, no imposition of narrative, the machine entirely subservient to reality. It’s a little disappointing, therefore, to see that the Nordlandbanen tranmission, as well as being a composite of four train journeys, occasionally features inset interviews with people travelling on the train, and has views not just from the front but from the side of the train. This turns what was pure journeying into tourism, into something with a purpose. The ideal is for the camera to be travelling at the front of the vehicle, with interruption, so that you are not aware of the vehicle at all but only of the sensational of travelling through space and time, seemingly endlessly. That is purity.

The Warwick Trading Company’s View from an Engine Front – Barnstaple (1898)

Such film journeys are almost as old as film itself. In October 1897 the Biograph company in America caused a sensation with a new kind of film when it released The Haverstraw Tunnel, which showed a New York train journey filmed from the front of the cab, with its most exhilarating feature for audiences being the point where the train went through the tunnel, the screen going black only to return to the light once again. Travelling shots from the side of trains and other forms of transport had existed before The Haverstraw Tunnel, but never before had a film turned the audience member into a disembodied figure in this way, hurtling ever forward through the screen. The film was soon billed as The Phantom Ride – Haverstraw Tunnel, and ‘phantom rides’ rapidly became a popular and regular feature of early film programmes, with most film companies jumping on the bandwagon and producing their own versions. An excitable but illuminating review of such a film journey, alongside other views, is provided by this 1898 Punch review:

It is a night-mare! There’s a rattling, and a shattering, and there are sparks, and there are showers of quivering snow-flakes always falling, and amidst these appear children fighting in bed, a house on fire, with inmates saved by the arrival of fire engines, which, at some interval, are followed by warships pitching about at sea, sailors running up riggings and disappearing into space, train at full speed coming directly at you, and never getting there, but jumping out of the picture into outer darkness where the audience is, and the, the train having vanished, all the country round takes it into its head to follow as hard as ever it can, rocks, mountains, trees, towns, gateways, castles, rivers, landscapes, bridges, platforms, telegraph-poles, all whirling and squirling and racing against one another, as if to see which will get to the audience first, and then, suddenly … all disappear into space!! Phew! We breathe again!!

Whether every early audience member’s experience of watching phantom rides was quite so phantasmagorical is open to question, though the appellation ‘phantom’ does suggest that they had an otherwordly, unsettling effect for some. What is now calming for a Norwegian audience was more energising for the audience of the 1890s for whom such a visual experience was wholly new.

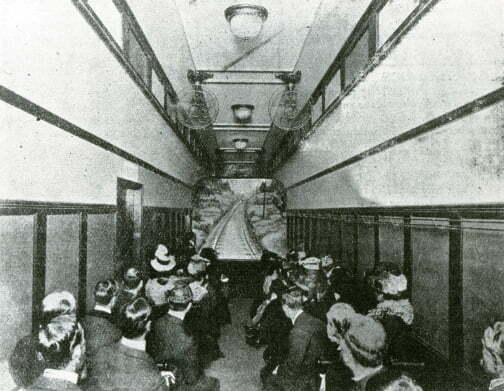

The strange relationship between spectator and screen, particularly at that point where you are sitting still but your mind is being propelled forward, became a major part of early cinema’s profound appeal, and its commercial success. Some of the first ‘cinemas’ were the famous Hale’s Tours – so named after their founder, George Hale – which placed audiences inside a mock-up rail carriage, at the front of which would be projected a film taken from the front of a travelling train (or other vehicle), while the whole carriage would rock to and fro to further the session of motion. Hales’ Tours (which originated in the USA and came to the UK in 1906) offered a variety of such film views for the ten to fifteen minutes such a show would last, emphasizing the touristic experience. But deeper than the wish to see far-off places was the wish to escape into travel, and to be forever travelling. The affinity phantom rides and Hale’s Tours have with the virtual reality concepts and amusement offering of today have been much commented on, but simulated roller-coaster rides and other such ‘4-D’ audiences attractions subvert the journey to a particular purpose. The pure film has no such purpose – it must simply take us on an uninterrupted journey, without cuts or deviations, seemingly travelling forever.

It is commonly argued that the phantom ride had disappeared as a film attraction by the late 1900s, to be subsumed as an attraction into larger film narratives, such as the opening titles sequence of Get Carter, or the prolonged car journey in Tarkovsky’s Solaris. But the phantom ride did not die, it simply transferred to forms outside the cinema. Amateur filmmakers took up the opportunity, particularly train enthusiasts, who have created what a variously known as cab rides or train cab videos. There are various companies selling DVDs and Blu-Rays of train journeys from around the world, each generally filmed from the front of a train and showing the journey from start to finish. Such ventures have certainly been going since the 1980s and probably have an older history than that.

In the age of ubiquitous video equipment and the rise of YouTube, such videos have moved online. There are hundreds of thousands of them, documenting every train journey imaginable from around the world. They are all over YouTube, plus numerous dedicated websites, as well as the individual train videos to be found on travel and train company websites (railway companies were the sponsors of train films from the earliest years, as they were seem as an easy form of free advertising). The video above is typical – a 90-minute rail journey from Wakayama to Osaka in Japan, made in 2012.

Nor are such videos limited to trains. The several videos of the meteorite that struck Russia in February 2013 were taken from the front of cars travelling along a road. The reason these video cameras were in place was not out of any desire to record the otherworldly beauty of travel on Russia’s roads (or indeed in the hope of recording a passing meteorite) but rather because of the reported corruption of some of Russia’s traffic police. Russian car drivers have taken to videoing their journeys to produce an objective record of what they were doing on the road, just in case they are stopped by the police and have a false accusation planted on them. There are, nevertheless, plenty of videos of car journeys that record the journey alone, often employing time-lapse – something probably introduced by the BBC’s famous 1952 ‘interlude’ London to Brighton in Four Minutes, which in form and intent seems very close to, if very much quicker than, the NRK broadcasts. There are motorbike and bicycle videos filmed from the front of the vehicle, and the whole sub-genre of commuter videos (well worth a post to itself one day).

Train cab videos are made by train enthusiasts with a passion for the rail experience rather than a desire for creating pure film. The NRK broadcasts are significant therefore, because their primary appeal is not train travel per se. It is not even touristic, or a patriotic sentimentality for familiar scenery, though both are obviously part of the local appeal. What seems to make the broadcasts works so effectively is how they gently take people out of themselves. We are disembodied. We float freely through the landscape at an even speed, and though we are on a journey that began somewhere and will end somewhere else, to all intents and purposes we are travelling endlessly. This seems to be what lies at the heart of the success of the NRK broadcasts. They are are so profoundly peaceful because they find that ideal space between stasis and motion. We are still and yet we are propelled forward. We are guided by safe hands. We are travelling hopefully, oblivious for a time at least to the fact that all our journeys must, inevitably, one day come to an end.

Links:

- The full 10-hour Nordlandsbanen journey and its seasonal variants can be found at http://www.nrk.no/nordlandsbanen, with a handy background account of the broadcast and the troubled history of the railway line itself here

- All 134 hours, 42 minutes and 45 seconds of the Hurtigruten 2011 coastal boat journey can be seen on this dedicated NRK site

- There is a good account of the history of the phantom ride on Brian Phelan’s The Stuff Dreams Are Made Of blog

- Another informed overview of the phantom ride genre is given by Christian Hayes on the BFI’s Screenonline site, with plenty of examples (available only to UK schools and libraries)

- The excellent Alexandra Palace Television Society YouTube channel includes London to Brighton in Four Minutes