I’m happy to announce the re-launch of Who’s Who of Victorian Cinema, an online biographical guide to the earliest years of motion pictures, 1871-1901. The site is based on a 1996 book of the same name, edited by Stephen Herbert and myself, which we turned into a website in 2003. It has undergone a major redesign, and I hope that in this new form it will continue to serve as a useful resource for early film studies and late Victorian studies in general.

That’s the headline – now here’s the story behind the site:

Back in 1995, when the centenary of cinema celebrations were looming, the then head of the British Film Institute Wilf Stevenson (now Lord Stevenson of Balmacara) brought two of his employees together to work on a centenary-related project. One was Stephen Herbert, an authority on early and pre-cinema technologies and head of technical services at the National Film Theatre; the other was a humble cataloguer in the National Film and Television Archive who had shown some keenness for first films and the people who made them – yours truly. We were asked to suggest ideas for a suitable centenary publication. We came up with the idea of a novel biographical guide to those who invented cinema. And so Who’s Who of Victorian Cinema was born.

It was a good idea. At a time when there was particular interest in the personalities around at the birth of cinema, and much debated about who had invented what, and who came first, we wanted to argue that no-one person or country had done so, and that indeed the phenomenon of cinema did not start at any one point, with antecedents that showed a more complex, nuanced and indeed interesting history. Further, we did not just want to focus on inventors and filmmakers. We were as interested in the subjects of the first films, the performers, the businessmen, the exhibitors. As we wrote in the book’s introduction:

What this book tries to do is to show something of the lives of the many hundreds of people worldwide who by their efforts in the closing years of the nineteenth century collectively invented the cinema. Scientists, entrepreneurs, doctors, sportsmen, artists, politicians, dancers, photographers, reporters, showmen, propagandists and crooks: the whole extraordinary variousness of the late Victorian era.

And so we plundered every source we knew of, collared every expert we could find to write entries for us – frequently on people for whom no biographical research had been undertaken before and about whom so little could be found – and worked hard to ensure that the book would be broad in its remit and international in its scope. Next to nothing had been written about the first films in South America and Russia, and research was only just coming through for areas such as Australia and Japan. It was a historiography still rife with anecdote and chauvinistic assumptions, and we were adamant that contributors should challenge old assumptions and wiote pieces that would stand up to modern scrutiny. I also saw the book not simply as a reference book but almost as a novel – a tale of invention with an extraordinary cast of characters, the narrative for which seemed clear at first but become all the more mysterious the more you looked at it, and which was an ever-changing story in any case because you could start the book at whatever point you liked and read it in whatever order took your fancy.

The book was published by the BFI in time for the centenary celebrations in February 1996 (one hundred years after the first commercial projected film show in Britain). It made a modest impression among a discerning few, ended up on some library shelves, and then quietly went out of print. But Stephen and I weren’t finished with it. We had both started developing websites, and saw the potential of re-inventing the book for the Web. In a burst of manic enthusiasm I got a trial copy of Dreamweaver from a computer magazine, fashioned a web design from a template provided, and entered 300 texts from the book into the website before the 30-day software trial was over. We added indexes to the film technologies, to countries and to groups (actors, sportsmen, magicians, monarchs, women) that would open up the research. We added weblinks, bibliographies and background materials. And in 2003 we re-launched Who’s Who of Victorian Cinema as a website.

It made a modest impression once more, and has continued to do so. Researchers, enthusiasts and descendants of the Victorians filmmakers themselves have got in touch with extra information, corrections, photographs. We added more names, we tried to keep the references up to date. But other projects cropped up (particularly other websites), and the site started to look a bit moth-eared. The information needed updating, but constantly reviewing 300+ pages was a huge task, and moreover the design of the site was no longer suited to modern widescreen PCs and modern browsers.

What is one to do with reference sources on the Web? How can you keep them constantly up-to-date? In the book world the answer is simple – you have a first edition, and if sales go well you have a second a year or so later when you can amend things, and if it hasn’t sold well then it slips into history and we wait for the next book that updates our knowledge on the subject. The Web has given us Wikipedia, which is a good solution to the need for an ever-evolving reference source, but Victorian cinema is still an area rife with anecdote and chauvinism, and we are wary of having old myths placed back in personal histories by other hands after having tried so hard to rid ourselves of them (as it is, much of our book had been plundered by Wikipedia). There still seems to be a case for maintaining a well-defined and responsibly-researched online resource, even if the price you pay for this is eternal watchfulness. History never stands still, which is what makes it worth pursuing.

There is an argument that the biographical approach is not the right one for film history, and that what really happened and what was really significant was not the product of individual, however colourful, but rather of industrial, economic and social processes of which the small world of film formed but a part. Of course that’s fundamentally true, but our purpose was to show the impact on people at that time. These were all people born into the mid- to late Victorian era whose lives were dramatically shaped by a new medium of which they had no prior preconception. It’s much like ourselves, born into a world without the internet, which has now changed utterly how we think and communicated, created new jobs, new words, new businesses, new ambitions. It is just such a dramatic change that the site documents.

So do take a look and find out not only about the established founders of cinema, such as Louis Lumière, Georges Méliès and Robert Paul, but also director Alice Guy, medical experimenter Gheorge Marinescu, explorer Mary Hitchcock, pornographer Eugène Pirou, dancer Ruth St Denis, writer Winston Churchill, magician David Devant, evangelist Herbert Booth, boxer Bob Fitzsimmons and mountaineer Mrs Aubrey Le Blond. All active in motion pictures in some form before 1901, all of them collectively inventors of the cinema.

Our grateful thanks go to the wonderful Bridget Designs who rescued the look of a site that had fallen sadly into disrepair, with such excellent results. It’s amazing how a fresh look can revive enthusiasm for keeping the rest of the site looking trim and up-to-date. And so Who’s Who of Victorian Cinema rolls on once more.

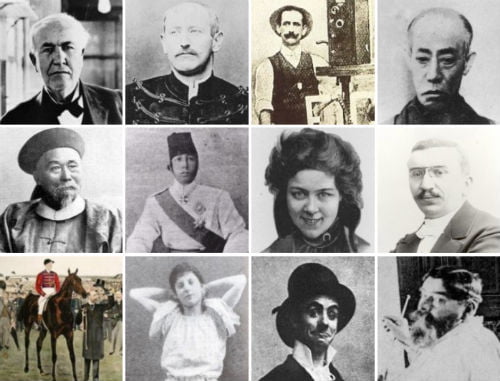

Those featured in the photographs at the top of this post are (left to right, going from top to bottom):

- Thomas Edison, American inventor

- Alfred Dreyfus, whose trial in 1899 led to actual and recreated news footage

- Brazilian film pioneer Affonso Segreto

- Danjuro IX, Japanese kabuki actor filmed (reluctantly) in 1897

- Li Hung Chang, Chinese politician who appeared in early Biograph films

- Abd al-Aziz, Sultan of Morocco, a cinematography enthusiast

- Loïe Fuller, American dancer whose Serpentine Dance was filmed several times, and had many imitators

- Louis Lumière, co-inventor with brother Auguste of the Cinématographe

- Persimmon, racehorse owned by the Prince of Wales and winner of the 1896 Derby, filmed by Robert Paul

- Ena Bertoldi, music hall contortionist and early performer for Edison’s Kinetoscope

- Dan Leno, hugely popular British music hall and pantomime artist who appeared in several early films

- French artist Louis Tinayre who filmed in Madagascar with a Lumière camera in 1898

Thanks for reissuing WWVC – I hope that it can be developed to add more material as that information is found and verified.

The IMDb is an example of a mass collective “well-defined and responsibly-researched online resource” – most of the time; the “eternal watchfullness” for it is the duty of the users and contributers as well as the editors – eg: I’m sure you will want to spend the seasonal holidays adding data from late 19th century – early 20th century cinema to the IMDb’s rather than watching some cricket matches on television :).

Meanwhile, in the 21 century, this gentleman looks as if he needs some substantial biographical details on his IMDb entry:

http://uk.imdb.com/name/nm2471225

We will continue to verify information and to add new material (the entry on Riley brothers was significantly changed this week and we have new material going up on Alexander Black his evening). We’ll also add new names as and when we can.

I agree that the IMDb works well as a collectively-produced resource, though I believe it’s now a heavily-managed one (it’s some while since I last contributed anything to IMDb). Maybe the right answer in the long-term will be to hand it all over to Wikipedia and trust that the truth will out, eventually. And there is a lot of cricket I’d rather be watching.

As for that IMDb entry … well it’s immortality of a kind, though I hope my whole life isn’t going be summed up as consultant on a WWI programme and an appearance as “silent film buff” on another. I do hope not.

My way of getting detailed knowledge about subjects is in working on Gloucestershire (including Bristol) “things”. On IMDb I add and correct Gloucestershire related material and have just added the correct outline bmd details for James Simmons Freer who was born in Woodstock, Oxfordshire, not Bristol as currently in WWVC (see his entry in the Freer Family Genealogy Research website). I shall put a link at JSF’s entry to WWVC asap.

I think the IMDb is the model now for general information listings for film, television, radio and theatre; it does, however, require heavy, labour intensive, management, as you imply. It is complimented by specialist sites such as WWVC and those for individuals (which also help counterweight the IMDb’s understandable bias towards English-speaking titles and names).

Amongst all the credits cataloguing the IMDb does include items to cater for its users’ entertainment: so you will, on your entry, after clicking the (currently empty) L MK Message Board, find an automatically-generated quiz all about you for the whole world to try, if they are so inclined.

You can control your IMDb “immortality” by adding biographical details and credits yourself (the more information about you that is added to the IMDb, whether by yourself or others, the harder the L MK Quiz will be, by the way). Remember that information in the general IMDb site is repeated in the IMDbPro one, alongside news and features, so your currently sparse entry is to be seen amongst those for the contemporary international film industry, including professional librarians and archivists – an incentive to make a personal entry comprehensive, perhaps.

To finish back with WWVC: how would you include the members of the cinema audience in it?

I’m fascinated by what sort of a quiz might be generated by my filmography – unfortunately there don’t appear to be any questions, though I see from other quizzes that they are divided up into easy, challenging and genius level. It would be genius-level to generate a quiz from a filmography of two!

Thanks for the tip about James Freer. I’ll investigate further and amend our record.

I am really interested in your suggestion about including members of the audience. We did include Maxim Gorky in the book, whose primary contribution to Victorian cinema was as witness to a film show, about which he wrote so eloquently. But there are others we could include, which would be appropriate to our wish to represent the diverse ways in which the moving image impacted on lives. One is Sydney Race, whose recently-published journals of the entertainments he saw in Nottingham in the 1890s include several precious reports on Kinetoscope shows and early film projections; another is Lady Colin Campbell, who wrote about seeing the film of the Corbett-Fitzsimmons boxing match (as did the American journalist Alice Rix). I will definitely look into this.

Yes, by “members of the cinema audience” I did mean those who can have some kind of entry on WWVC as either individuals, (ie:”witnesses” such as known writers like Maxim Gorky or discovered unknowns like Sydney Race) or collectively as _filmgoers_ rather than merely customers and viewers.

Regarding “filmgoers”,when did they become distinguished from “theatregoers” and what were the first collective nouns for them? Further topics may be early fans of particular cinemas, producers, directors or actors, again, as individuals or groups (as far as they can be indentified at present in the period WWVC covers).

One subject to be researched from early cinema audience-study is which filmgoers realised that what they were watching was a new medium and that it would develop in ways yet to be known – how many of them “got” cinema?

There is a comparison here (closer than some may think at first) with one of your other interests, William Shakespeare; if only there were more surviving reporting of the plays, players, playgoers and playhouses of Shakespeare and his contemporaries…

WWVC is about individuals rather than crowds (though I’m slightly tempted to include a whole audience somewhere – maybe all those who ran from the sight of the Lumiere train, if only that most apocryphal of film stories had actually happened).

You raise some interesting issues about the perception of cinema, some of which I’ve tried to address in writings on early film, but not enough has been done on the first film audiences – indeed hardly anything at all (I’m doing a bit of research, but early days as yet).

The Shakespeare parallel is apposite. What is a play without a crowd to witness it? What is a film without its audience?

Congratulations, Luke. And thanks for unrelenting blogging.

Thanks Karel, though ‘unrelenting’ worries me a little. I have given up blogging via the Bioscope and hope to manage this blog a little more casually…

Aiming to be as good as my word, there’s a new ‘group’ on the Who’s Who of Victorian Cinema site, ‘Audience members’: http://www.victorian-cinema.net/groups.php#audiences. The new entry that has kicked this off is Sydney Race – http://www.victorian-cinema.net/race, though I’ve added pre-existing entries for Gorky, Queen Victoria and a couple of other royals to beef up the section a bit. Lady Colin Campbell should follow soon.

Thank you for adding the Audience group to WWVC and for the inaugural Sydney Race entry; he was, from your description, an archetype of one of the parts (self-educated doer, looker, listener, recorder) of the first cinema audiences I was thinking of when I wrote my earlier comments here and in response to your own recent cinema visit report.

One of the other audience parts would be of those who were at the auditorium (theatre? – or cinema?) “merely” to be entertained. If – if – they have left memoirs of their experiences, it may be possible to get a sense of what the supposedly unsophisticated thought of the new medium.

Something else to look out for is what I mentioned above, the first notice of the film-going audience as a collective body that was separate from the theatre going one and whether their opinions were recorded (as they became a recognisable customer base the makers and sellers of cinema will certainly have taken note of them).

Who’s Who of Victorian Cinema was closed for any further updates at the end of 2020. The site will remain online, we’re just not changing anything from this date further. See https://lukemckernan.com/2020/12/29/farewell-the-trumpets