Time was when little was written about colour in film, or colour in the arts generally, except for technical studies. You could read about how a dye or a pigment was made, or how a colour film projector operated, but little about the significance of colours, be that culturally, socially or even aesthetically. Michael Pastoureau, one of the foremost writers on colour today, describes the situation in the 1970s when he first sought to research colour, in his entertaining memoirs, The Colour of our Memories:

At that time, among historians, archaeologists and art-historians, nobody, absolutely nobody, showed the slightest interest in colours. Even in fields in which it was reasonable to suppose one would discover ongoing studies on such a subject, colour was conspicuous by its absence. The history of clothing, for example, was a totally colourless history. Although documentation existed, masses of it, costume specialists were not interested. All that mattered were the archaeology of shapes and the nature of the various garments that had made up clothing over the years. The idea of a ‘clothing system’, lodged at the heart of social life and within which colours might have played an essential role, was completely foreign to them … But there was worse to come: the history of painting. In this discipline in which colour should, by its very nature, have occupied a place of the first importance, it was almost always passed over in silence … Colour was the great missing element in the history of art.

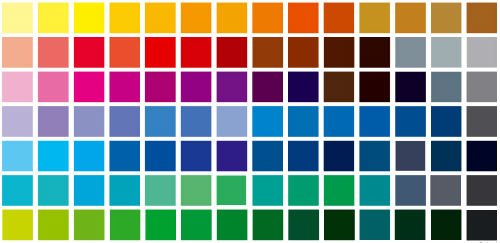

One feels that Pastoureau is exaggerating for emphasis, but there is a general truth underlying his complaint. Colour theory is probably as old as the human ability to reproduce colours, with certain colours being said to denote particular absolutes (blue for cold, red for anger, green for go, and so on), but as Pastoreau has pointed out, different colours mean different things to different cultures at different times. Colour is socially determined, and all those artists, designers and theorists who have assumed that colours are immutable in their significance are guilty of so much vain folly. The limitations of colour reproduction in earlier decades may have had something to do with the neglect: look at all those art books in the second-hand stores and forgotten corners of libraries with their black-and-white illustrations of works of rich colour. It was hard enough to see such colours, let alone imagine them.

There has been a huge shift in colour scholarship in recent years (not unconnected with huge improvements in our ability to reproduce such colours in the printed page and on screens). The works of John Gage on colour in the arts and of Pastoreau across a wider frame of cultural reference, have helped put the study of colour to the forefront of many disciplines. The amount of speculative guff written about the significance of colours has grown exponentially as well, for writing about colour seems to lead inevitably to the romantic and the tendentious. Understanding how colour works requires not just an aesthetic sensibility, but a technical understanding, and a socio-historical one too.

So it was that these words from Sarah Street’s recently-published Colour Films in Britain: The Negotiation of Innovation 1900-1955, talking about Technicolor films of World War II, leapt out at me:

The positive reception of British colour films at home and abroad created interest in what directors and technicians were doing with colour. A British colour aesthetic was being developed and appreciated. In broader terms, these examples demonstrate how cultural and material contexts impact on aesthetics and influence how technology works.

This is the heart of the matter. We need to understand how the cultural and the material impact upon aesthetics not only to appreciate the art of colour film, but to understand the technology. There are many guides to colour film technology which are useful in understanding the mechanics, but not in understanding the impact. Equally there are many texts which wax lyrical on the impact of colour and overlook the processes that made such colours achievable. It is the great strength of Street’s book that it negotiates equally innovation in aesthetics and technology, knowing how technology worked in a literal and a psychological sense (Pastoreau is poor when it comes to explaining colour film processes, by the way). It is a substantial text (with rich colour illustrations) that traces British colour film history from Kinemacolor, to Prizmacolor, to Dufaycolor, to Technicolor. It covers the celebrated works of Powell and Pressburger (The Red Shoes, A Matter of Life and Death, Black Naricssus, Gone to Earth), the less familiar colour features of 1940s British cinema (Jassy, The Man Within, Blanche Fury), 1930s animation (Len Lye, Norman McLaren), colour in non-fiction film (Western Approaches, XIVth Olympiad – The Glory of Sport), the cinematographers, camera operators, colour specialists (the oppressive presence of Natalie Kalmus, who tried to dictate how Technicolor should look), the economics and the idealogies. It comes with an invaluable Technical Appendix, written by Simon Brown, which summarises all of the colour film processes in Britain 1900-1955, and a handy filmography of colour films released in the UK 1938-1955 (somewhat curiously ordered alphabetically by title within each year).

Street’s book is one outcome of an AHRC-funded project into British colour film that Street headed (declaration of interest – I was on its advisory board). Two other books from the same project are out next year: British Colour Cinema: Practices and Theories, edited by Street, Brown and Liz Watkins, which is a series of interviews conducted with British film colour practitioners – not just cinematographers and camera operators, but those involved in the restoration of colour films and their release on DVD in recent years; and Color and the Moving Image: History, Theory, Aesthetics, Archive, a set of essays from the same editors.

And there’s more. Street is now heading a Leverhulme-funded project into colour film in Britain in the 1920s, which should be an interesting challenge. Her co-investigator (in the language these projects tend to adopt) is Josh Yumibe, who has his own book on colour film just published: Moving Color: Early Film, Mass Culture, Modernism. This looks at early colour film processes where colour was manually applied through hand-colouring, the use of stencils, tinting and toning. It’s not the whole story of early colour, which I find a bit disappointing, because there were natural colour processes at the same time, notably Kinemacolor (there is a strong chapter on Kinemacolor in Britain in Street’s book). But Kinemacolor is difficult to get hold of, still harder to see projected as colour (a piece of Kinemacolor film appears to be black-and-white – the colour effect only appears when it is projected through a rotating red-green filter). The aesthetics of applied colour (film archivists wax lyrical over the beauties of early coloured films) win out over the full history, but Yumibe explains clearly that his eloquent and knowledgeable history is intentionally a selective one. But the complete history of early colour film has yet to be written.

Do we want more? Well there is more. Here’s a quick bibliography of other recent works on colour cinema:

- Patti Bellatoni, If It’s Purple, Someone’s Gonna Die: The Power of Color in Visual Storytelling (2005)

- Paul Coates, Cinema and Colour: The Saturated Image (2010)

- Angela Dalle Vache and Brian Price, Color, The Film Reader (2006)

- Eirik Frisvold Hanssen, Early Discourses on Colour and Cinema (2006)

- Scott Higgins, Harnessing the Technicolor Rainbow: Color Design in the 1930s (2008)

- Richard Misek, Chromatic Cinema: A History of Screen Color (2010)

- Steven Peacock, Colour (2010)

It’s a crowded shelf all of a sudden. I have great interest in the subject myself, chiefly through having studied Kinemacolor for several years. Kinemacolor is a model subject for an understanding of colour in its cultural contexts. Kinemacolor seen today is not the same as Kinemacolor as it was seen in its 1908-1914 heyday. In a literal sense it was a limited colour system because its red-green filter excluded the primary colour blue, so it could not reproduce the full colour spectrum. That’s what we see if we’re lucky enough to witness Kinemacolor today. But is that what they saw 100 years ago? Audiences of the time were often (though not always) transported, believing that they had seen colour perfection. But this was as much due to the films’ subject matter as their colour – Kinemacolor specialised in films showing British royalty in their imperial splendour, such as the coronation of George V, the investiture of the Prince of Wales and the 1911 Delhi Durbar ceremonies. What was seen on the screen was infused by a belief in the special significance of what was being projected. It was how the technology worked.

Colour belongs to the times in which it was created, always, and when we look back on colours, and try to recreate or restore those colours, we do so inescapably through the eyes of today. Colour film restorations today are usually brighter, less subtle than they were when the films were first released – see Martin Scorsese’s editor Thelma Schoonmaker complain about this in a recent fine article on digital versus traditional film by Daniel Eagan. But that’s the contemporary taste. We see things differently. Seeing how colour was understood in times past may be physically beyond us. But at least we can read about it.

Links:

- Professor Barbara Flueckiger of the Institute of Cinema Studies, University of Zurich has created an illustrated online historical timeline of motion pictures colour processes

- The best technical history of motion picture colour systems remains that included in Brian Coe’s indispensible The History of Movie Photography (1981)

- David Cleveland and Brian Pritchard discuss how they have gone about recreating Kinemacolor today on Pritchard’s very useful motion picture archiving site

- Thinking that there should be one book on colour on your shelves? Then this is it: John Gage, Colour and Culture: Practice and Meaning from Antiquity to Abstraction. It will open your eyes. Failing that, Michel Pastoreau’s Blue: The History of a Color.