Of all the ephemeral objects we build for ourselves in the digital world, among the most precious and at the greatest risk of disappearing are databases. Databases are organised and queryable collections of data. The larger ones, along with their cousin the content management system, govern our world and manage who we are, since their very existence decides that we must be categorised in a particular way so that the relationships we have with other people, objects and concepts can be drawn and managed.

Such monster databases as drive Amazon, Facebook, Google and the like are not going to disappear. But smaller databases, created to manage an area of learning, are at risk. They cannot be archived in the way other web objects can be archived, because the web does not expose the underlying structure which enables database queries to be made. There are means to preserve the contents of databases though assorted digital preservation strategies, but they preserve the essential characteristics of the data, not the living, designed entity. Databases need to be hosted, managed, designed, and – to remain meaningful – to be constantly and unendingly updated. A reference book, once published, is what it is, a statement of how things were at a particular point in time. A database has no such fixed status – shark-like it has to keep on swimming, or else it dies.

There have been thousands of databases generated by academic projects over the past two decades. Research funds have been made available to collate information on a subject in the form of a structured list, because you can never go wrong with a list. It’s one of the basic frameworks through which we understand the world, ordering things by value, time, number, category or whatever. Everything finds its meaning and its place in a list, and a database is just a list extended into its most useful form.

These databases are wonderful things. They have been the bedrock of my own researches, and among my favourites in the film history field are Going to the Show, Filmportal, Catalogue Lumière and the American Silent Feature Film Database. I’ve helped create or sustain a few databases myself, happily all still available online: News on Screen, The International Database of Shakespeare on Film Television and Radio, The London Project.

But once the academic investigation is done, and the research funds are spent, someone has to keep the database going. Usually that’s down to a university, which will keep the database chugging away in its servers, but the money to keep the appearance fresh fresh and the content updated will have gone. Sometimes a volunteer will devotedly be able to do just enough to keep things ticking over, but most – though not all – academic databases eventually fade away, untended and eventually forgotten. They become digital rust.

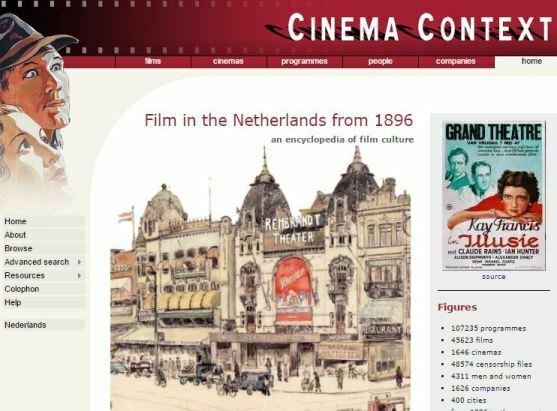

I have written in praise of the website Cinema Context, which Karel established, on several occasions. Indeed my words of praise about the site, which documents film in the Netherlands since 1896 by linking films to the cinemas where they were shown, can be found on its front page, put there not long after I reviewed it on my Bioscope blog in 2007. This is what I wrote:

What is the finest film reference source on the Web, for all film let alone silent film? With all due respect to the Internet Movie Database, I think it is Cinema Context, a Dutch site created by Karel Dibbets and the University of Amsterdam. Describing itself as “an encylopedia of film culture”, the site documents film distribution and exhibition in the Netherlands in 1896. It does so through four data collections, on films, cinemas, people and companies, derived from painstakingly researched data on nearly all films exhibited in Dutch cinemas before 1960. The research team located film programmes from 1896 onwards in each of the major Dutch cities, entering all film titles, names, dates, cinemas etc, and then ingeniously matched this data to the records of these films on the IMDb.

The result is an incomparably rich resource for tracing films, the performers and the producers across time and territories, opening up whole new areas of analysis. Cinema Context also contains comprehensive data from the files of the Netherlands Board of Film Censors 1928-1960. As the site states: “Cinema Context is both an online encyclopaedia and a research tool for the history of Dutch film culture. Not only can you find information here about who, what, where and when: you can also analyse this information and study patterns and networks. Thanks to Cinema Context, we are now able to expose the DNA of Dutch film culture.” Naturally, it is available in both Dutch and English.

This is the new film research. Every nation should have the same.

I still stand by the words, all the more since many extra features have been added since 2007. Cinema Context is dedicated to demonstrating the interconnectedness of film, and by extension is devoted to expressing the principle of meaning through linking, or the logic of context. Film, as with any other subject, only has meaning through its relationships with other subjects. Otherwise all you have a topic that exists only in splendid, self-justifying and ultimately meaningless isolation. It has to be said that too much of film studies exists in just that state of splendid isolation, and the passion that the few, such as Karel Dibbets, have felt for mapping (in every sense) cinema’s relationships has yet to make its way into the film studies mainstream. But it will do, in time, and if the databases are allowed to survive.

Happily Cinema Context continues, maintained now by Professor Julia Noordegraaf at the University of Amsterdam. May it always exist. A book, once published, remains on a library shelf, to be consulted forever more. The same must be promised for databases. More than web texts, which do little more in the communication of knowledge than printed texts had done before, the database is of one the great new academic gifts of our time. We should be doing all that we can to preserve them. They are labours of love, and the labourers are few.

RIP Karel, with many thanks.

Links:

- There are various database preservation projects and solutions out there, including LOCKSS (‘Lots of Copies Keeps Stuff Safe’), database-preservation.com and the Open Preservation Foundation

- I wrote two blog posts on Cinema Context – the original, quoted above, in 2007, and a follow-up with more information in 2011

- Dutch film scholar Ivo Blom has written a fine, long tribute to Karel Dibbets on his personal site (with a great photo of Karel where he always liked to be, at a good restaurant table): In memoriam: Karel Dibbets (1947-2017)

Great Post Luke, for all of us researchers especially who rely on these databases many time as a focal point of beginning our research and in many cases, it turns out the culmination of research. Many of us during the course of our research develop our own databases which in many cases never see the light of day, while this is not the focal point of your piece it falls into the same general arena. What happens to these “home grown” databases once they have served their “initial” purpose?

Folks like Karel Dibbets are most important to researchers/historians and the like not only for the fact they take on the task of keeping the databases updated and accessible but for the wealth of knowledge they possess and are wiling to share.

That’s a really good point about home-grown databases. I have several myself – OK, they are spreadsheets, but that’s a database of a rudimentary kind. And I know many other researchers have the same. The problem is that they are viewed as works in progress, as well as being the products of precious personal research that they don;t want to give away too early, so can end up never getting shared.

I ought to do something about this, at least for myself. I have published some lists on this site (under Publications) but they’re not easy to find. I could have a new section on Data, and make more lists available that way. Maybe when I’ve finished the current work in progress, Kinemacolor…

Luke, Thanks so much for your thoughtful post about Karel and about Cinema Context. I can remember being in a seminar room in Amsterdam where Karel arranged for a presentation of the prototype of Cinema Context. It was one of those “ah ha” moments and a break point between what had been possible when you had breakfast that morning and what would be possible from that time forward. “Going to the Show” was certainly inspired by Cinema Context. For me, one of the greatest values of Cinema Context was what we might call its generative capacities: implicitly pointing the field of cinema studies to new opportunities in other places. Karel was also such a generous and kind colleague and friend. One of the high points of every conference we both attended was the opportunity to have a meal or a coffee with Karel.

Hi Bobby,

Thank you for your comments and fond memories of Karel. I felt when I first saw Cinema Context that it was pointing out the new direction for cinema studies. Going to the Show confirmed this. It’s all about those new opportunities.

Luke

Luke, Thanks for the kind nod to “Going to the Show.” It was in danger of being “shuttered” a few month ago, but my great technologist partners in UNC’s Office of Arts and Sciences Information Services (OASIS) migrated the whole project into their shop, not only saving it but making it more robust and stable: http://gtts.oasis.unc.edu/

One quirk: as you zoom into the Sanborn Maps, the viewer might throw you out of map mode. To restore it, just press the map icon beside satellite.

This was an existential lesson for me on the half-life of digital projects: GTTS took more than two years and more than $200,000 to build. It is only 8 years since its launch in 2009.

Which only goes to prove my point. I am delighted that Going to the Show has been migrated to a more stable platform, but greatly concerned that it was ever under threat in the first place. The problem is a combination of the short lifespan of digital objects in a forgetful age, and probably a limited view of what a database is there for. It should attract use and encourage further research, of course, but it is also a publication in its own right. We don’t burn books; we shouldn’t close down databases.

(For anyone interested, here’s what I had to say about Going to the Show back in 2009: https://thebioscope.net/2009/07/19/going-to-the-show/)

Wonderful Luke, very well put; we’ll do our very best to maintain and extend the database in Karel’s spirit – feel free to remind us of that responsibility whenever needed.

Hi Julia,

In writing the post I was thinking of a number of databases that I feel are at risk, but thought it diplomatic not to identify them. However, Cinema Context is in very good hands – but I will write reminders every now and again, if only because I’ll want to keep advertising it.

I look forward to seeing it grow.

Luke

Great piece Luke. (Predictable response from me…) The half life of databases is something we all need to keep in mind, and we need to keep our organisations aware of the benefits of maintaining, publishing, developing, migrating, replacing them. The ROI is not always transparently clear to an organisation, so every bit helps – e.g. referral traffic from blog posts….

There need to be rules put in place. There has been a lot of good work done on the principles and practicalities, but I’m not aware of much having been done on responsibilities. In the UK we used to have the Arts & Humanities Data Service, which laid down rules and took in copies of databases created out of research council funding. But the AHDS had no preservation solution for itself and was wound down. To the best of my knowledge it has had no successor, though there are assorted advisory services out there.

But where does the responsibility lie? With the academic who created the database, with the institution that first hosts it, or with a centralised archive? It doesn’t seem clear.