To Antwerp for a few days, a city I had not visited before, and my first trip abroad in over three years. The place I found entrancing. It is the kind of city where every space seems best designed to catch the eye, where every side turning becomes a worthwhile adventure, an art statement in itself as well being a fine centre of art and culture.

There are the galleries and museums that you would expect – the Rubenshuis (or Rubens’ house), the Museum of Contemporary Art, the Royal Museum of Fine Arts; the Cathedral of Our Lady with its startling white interior (and Rubens paintings); the extraordinary Schoonselhof cemetery to the south of the city, with its gravestones of artists made like works of art; the enticing Kloosterstraat with its galleries, antique shops and home interiors places, designed to make you want to cast out every chair and table you may own and start again with their eyes; or simply the Marian (Mary) statues perched up high at so many street corners.

But the finest location is a museum, one of the finest museums I have ever encountered: the Museum Plantin-Moretus.

The Museum Plantin-Moretus is a museum of printing, which sounds dry enough as a topic, but what it is really is a monument to humanism and the business mind. To visit the museum is to learn how successfully the Western world has shaped itself.

Christophe Plantin (c1520–1589) and Jan Moretus (1543-1610), his apprentice and then son-in-law, were printers based in Antwerp in the sixteenth century. Plantin was a French bookbinder who moved to Antwerp shortly before 1550, establishing a printing business in 1555, which would become the largest printing business in the world at that time. He did so despite working at a time of deep religious controversies, when the Southern Netherlands were under Spanish control and Roman Catholicism was strictly imposed (early in his career he had to flee Antwerp for Paris for a year and a half after a Calvinist text was found at this printing office by the authorities). A Catholic himself, Plantin would print works on different sides of the religious passions of the day, doing so anonymously where it was prudent to do so. Religious texts formed the backbone of Plantin’s business, and he could produce them for strategic as much as commercial reasons, notably when he produced his famous multilingual Polyglot Bible, an edition of the Bible in Latin, Greek, Hebrew, Chaldean and Syriac, which gained financial support from King Philip of Spain.

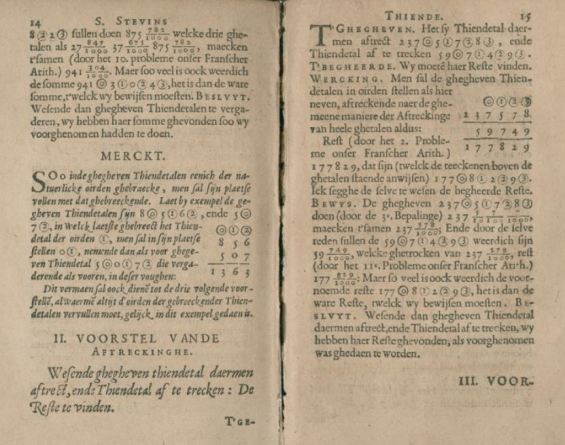

At the time he produced the Polyglot Bible (1568-73), Plantin was managing sixteen presses, employing thirty-two printers, twenty compositors, three proof-readers and assorted servants, a level of production capacity far in advance of his competitors. Over thirty-four years he published around 2,450 titles. Setting aside minor works, such as advertising sheets and news notices, Plantin on average produced a book a week, with print runs between 1,000 and 1,250 copies. As the Museum website notes, “This is also the average number of sheets that two printers can process per day on a single press. In the case of successful books, the print run was sometimes as high as 2,500.”. The highest circulation figure he enjoyed was for the Hebrew Bible in 1566, for which 7,800 copies were printed.

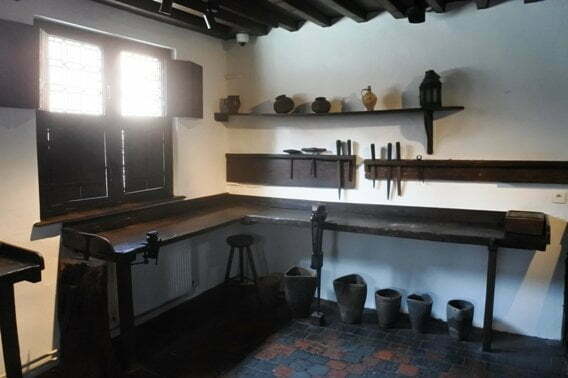

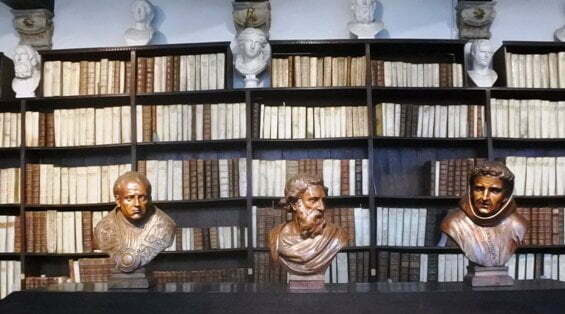

The Museum Plantin-Moretus shows us the mind of its founder. It is located in what was the printing works and family home, in Vrijdagmarkt, Antwerp, to which he moved in 1576. The rectangular, two-floored building surrounds a courtyard garden. The visitor goes through rooms where the family lived (portraits by family friend Rubens grace the walls), the printing office with original presses and trays of type, examples of publications produced by the press, a magnificent library (with books marked with slips, ready for digitisation by the Google Books project), and even the shop to the side of the building where clients would call (a list of prohibited books hanging on the wall to check against any request for forbidden text or questionable writers and printers). The wooden floorboards creak with resounding sixteenth century authenticity. The building itself is a UNESCO World Heritage site (the only museum anywhere to be so), while in a rare (unique?) double coup, its archives are inscribed on UNESCO’s Memory of the World register.

One sees, and hears, a world perfectly preserved. It is not simply the spaces, the technologies or the artefacts that so impress, but the mind behind it – because it is a mind that we can so readily recognise. Plantin and his colleague and successor Moretus firstly rose above the divisions of their time (at much personal risk) to champion enquiry. The Plantin press produced not only religious works but maps, music, dictionaries, mathematical, scientific and biological studies. Both content and approach were absolutely evidential, inquisitive, scientific. We understand the approach and the appeal to intelligence.

Next, the business strategy is one that we recognise. Plantin pursued quality. The Plantin press produced works that took the extra step necessary to ensure excellence, be that in languages used, the quality of illustrations or simply innovation in form (for instance, Plantin printed what is held to be the first atlas, that of Abraham Ortelius, in 1570). He targeted an audience of clerics and academics who were willing to pay more for the best. Astute branding, most visibly the compass design which can be seen throughout the building (it’s there in the portrait at the top of this post), on paintings and on the printed works themselves, creates a unifying sense of the product which reflects its exploratory, world-encompassing ambitions. There is a playful digital display in the museum on the history of technologies of communication, which links Plantin to Steve Jobs. It is hard not to think as much of the iPhone as the printing press when touring the Museum Plantin-Moretus. Each were perfectly attuned to the aspirations and the urge to communicate of their times.

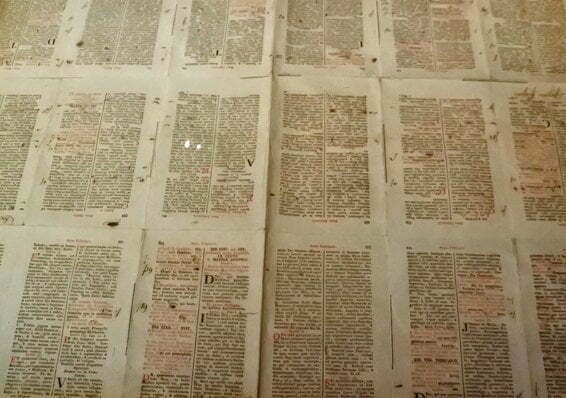

Thirdly, and probably most importantly, there is the clarity. The thing that struck me most about the Plantin texts on display was how readable they were. They immediately caught the eye, inviting you in. They understood texts as something read rather than revered. Plantin became famous for his type – we are still using Garamond, a font regularly used by Plantin, while another of his fonts influenced the ubiquitous Times New Roman, and the familiar Plantin typeface is named after him. But it’s not just the clear fonts and our familiarity with their curves and edges. It’s the spaces in between. No matter what language they might be in, the pages speak out to us in their clarity. We want to read them, when for say a medieval illuminated manuscript we do not. They understand that the eye is connected to the brain. Their very form gives us room to think.

House, products and papers were preserved by the family until the Moretus family sold all to the City of Antwerp in 1876. The impulse for preserving the artefacts of family and business seems not simply to have been pride but as demonstration of good work, the study of whose impulses and effects would benefit future generations. I kept thinking of the papers of Francesco di Marco Datini (subject of Iris Origo’s famous historical study The Merchant of Prato), the medieval Italian merchant who ensured his huge collection of business papers would survive so that a future world might understand and marvel. Sometimes the past understands us so well.

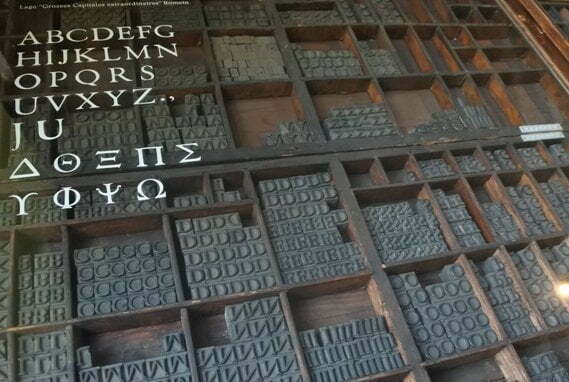

Of all the objects on display, it was the type cases in the Plantin-Moretus printing room that struck me the most. They are singularly beautiful, and uplifting. Here is every letter in every language with which it was wise and useful to speak. There they are, lined up to communicate, to translate and to share. It is as great an expression of knowledge and the good as one could hope to find.

Links:

- There is a great deal of accessible and well-illustrated information, in English, French, German and Dutch, on the Museum Plantin-Moretus site.