I live in a walled city. (Technically, I know, Rochester is not a city, owing to an administrative blunder back in 2002, but let’s keep to the romantic). It is not a place where the ancient walls survive largely complete, therefore circumnavigating the city, as is the case with Chester or York. Only fragments remain, but impressive enough in places and still marking out the centre from which power and privilege traditionally radiated.

The walls were originally Roman. Parts of these survive, mixed up with the reinforcements of later eras, while some foundations lie underground, with lines along the pavement marking out their position below. The walls were first built in the late second century AD, as an earth rampart with ditch, southwards from the river and the high point now occupied by a castle which was probably the location of the Roman fort. Early in the third century the walls were re-built in stone, encircling a wedge-shaped area of around twenty-three acres. The walls survived the decline that followed the departure of the Romans in the fifth century, and assorted assaults and sackings that were the lot of Dark Ages life. The Anglo-Saxons built a cathedral within the walls in the seventh century; in the eleventh the Norman added an imposing castle, the outer walls of the bailey following the line of the old walls where they touched the river.

The walls were built and rebuilt over these times, and in the fourteenth century extended further south, twice, as the city grew. Originally there were four gates – north, south, east and west, in the helpful regular fashion – though today all that remains are the names of north, south and east in present-day locations, plus Priory Gate, part of the fourteenth-century extension. The walls continued, defining the city, until the eighteenth century, where their increasing irrelevance resulted in much of them being destroyed with greater effectiveness than ever was achieved by the Danes.

Today only fragments survive. Aside from the castle itself (which looks as fresh as any one thousand year-old building could hope to look), the most prominent section of the walls (eastern side), with a fine bastion, runs alongside a car park, curiously unheralded. Other stretches pass through private gardens and the King’s School grounds, emerging from these to burst through into a wine bar, accurately named The City Wall. One can trace most of the lines that the three incarnations of the walls took, avoiding private land and having to use one’s imagination to conjure up what was once there. But real, buried or imagined, the walls are still there, circumnavigating.

In such towns and cities it is considered a good thing to be ‘within the walls’. Estate agents highlight its virtues, house prices reflect it. Not only are you towards the centre, but you are contained; all that lies beyond merely sprawls. This will always have been so. To be in the centre was to be near the castle and adjoining cathedral, one ensuring protection in the here-and-now, the other in the hereafter. Wealth and privilege brought you both physical and spiritual protection. Walls were not simply defensive, they defined who you were. Steve Nye, curator of Rochester’s Guildhall Museum, in an intriguing interview about the walls, says:

Roman town walls are a bit strange, because they aren’t a military thing. There is a difference between a walled town and a fort. Now, Kent’s got a lot of forts, but they are military sites. With the town, when you put a wall around it, yes it is a defensive feature, but it is also an urban feature. It is like a town growing up. When it is laid out, especially in Roman times, it was laid out with plots, and they built the houses within this, and they built an area which would be for trade and an area for a market, like a forum space, and they would have an earth wall around it. It defined the space. Now, a lot of Roman towns, they just replaced the earth wall with a stone one, so it is almost a status thing. Yeah, obviously access and defence but it is more about urbanisation.

The Roman didn’t build walls simply for defence, but because walls made a town (or city). They were how a town ought to look. There was a formulaic efficiency to it, of course – the Romans built their towns to a model, much as they built their forts: quick to construct, and you would always know where you were once you entered one – but there was sentiment as well. Walls look good. They define a place.

So why did towns and cities have walls, and why don’t they do so now? Lewis Mumford, in The City in History, argues that the first walls may have been built for religious reasons, identifying the limits of a sacred space. We have this profound need to draw circles that place us at their centre, to define the understanding we have of ourselves physically. This may be sacred in origin (or else it encouraged sacred thought). However, walls were built most practically for defence, emerging when people started gathering together and needed to protect themselves from the threat of outsiders.

But when you have built a wall, that must only attract the outside who covet what you have within those walls. You advertise your wealth and vulnerability. You advertise your difference, and peoples have always attacked those who they see as different.

Walls are fundamental to human history, yet history books tend to take them for granted. Who writes about walls? One book that does, and does so extremely well, is David Frye’s Walls: A History of Civilization in Blood and Brick (2018). Frye looks at walls over four thousand years, from Ur to Trump, asking all sorts of intriguing questions about what they are doing there and how the define what lies within, and without.

And what about these fears? Were civilizations – and walls – created only by unusually fearful peoples? Or did creating civilization cause people to become more fearful?

This chicken-and-egg question might be unanswerable but is fundamental. After all, there did not necessarily have to be walls, even in more hostile times. The Spartans did not build walls. It would have been a sign of weakness, something that defined the other Greek states and not them. To build walls would mean that you were weak. It was part of a policy that rejected the progress of civilization, that looked back to a pure age before peoples corrupted themselves with pleasurable things, which they then needed to protect.

Walls were something that the Spartans feared. Within them lay cultivation of commerce, the arts, philosophy, democracy, ways of understanding and managing the world that did not put weapons first or the mentality that went with them. Walls were a product of war, but pointed to a world that had no need or war, or Spartans. Meanwhile those inside the walls looked on admiringly, and perhaps with not a little shame at their softness, at the pure and primitive Spartans. But they were grateful to be inside.

Of course it took a long time before the walls could start coming down. It took the invention of gunpowder and cannonry capable of blasting through defensive walls to render them redundant, combined with the rise in the civilised society that had been nurtured by those within the walls. Walls had flourished because they contained something worth defending. They nurtured the growth of civilizations, the towns along the Roman roads lined up like so many gardener’s pots, propagating.

So how do we live now, without walls? Nye speaks almost as if building walls for today’s towns and cities might be a way of saving us from the disorientation of modern lives:

What changes is when you go to a completely modern place, like some of the new towns that were built, like Milton Keynes, they have no shape at all, that is why people don’t like them. Although they are laid out nicely and they have their gardens, they have no identity. City walls gave people a focus, there is a psychological value to them. People knew where they are, the walls helped to define where the roads were. It is kind of a definitive thing. It goes beyond the sheer practical nature of it all, but it goes into the psychology of a settlement and I think there is a lot to that. A lot of modern developments in this area are shapeless, lots of long roads and curvy roads that don’t go anywhere and you end up having no orientation.

Yet we are building walls all the time. David Frye argues that, since the new millennium, we have entered the ‘Second Age of Walls’ (gunpowder having brought about the end of the First). Mass migration and fear of terrorism, have seen a frenzy of wall building, albeit more for borders than cities. There are an estimated seventy-seven border walls or fences around the world, many built since 11 September 2001. Saudi Arabia began a barrier along its eleven-hundred-mile border with Yemen in 2003. Another wall covers six-hundred miles of the border with Iraq. Israel has surrounded itself with walls. India is lining its borders with razor wire, stretching into high mountain ranges. From Clinton to Trump, America has been building a wall along its border with Mexico, attempting to block the flow of immigrants (earlier presidents called it a fence; Trump discovered that calling it a wall got him more votes). Wealthy, fearful people in the USA and South Africa have built gated communities to keep out their idea of barbarians. And China has built its Great Firewall, blocking the dangerous online intelligence of those beyond its borders from those who must shelter within.

Is any of this civilised? Are fear and civilization essential companions? Or should we have moved beyond such things by now, if we consider ourselves civilised? To contain is to define, and to define is to contain. Walls reflect stability when we find the world outside unstable. It’s an idea more powerful than gunpowder.

It seems long way off from humble Rochester, with its fragmentary walls defending no one. But there is something about them, as they have survived, that is emblematic of the dilemma. The walls ebb and flow about their city. Sometimes they are solid, sometimes breached. Parts are in public areas, others lie in private lands that are themselves gated, walls hiding walls – from tourists and neighbours beyond the pale. They move from the visible to the invisible, maintaining the circle while breaching it.

I can imagine Roman Rochester, its inhabitants as confident as they could be and yet fearful as they had to be, living within their gated commune. There is some shame at their weakness, some begrudging admiration for the barbarians beyond who live in a fearless world, mixed with gratefulness for the thickness and height of those stone walls. Now they can discuss the finer things. Then I step across a line marking where a wall once stood, and I do not know whether I am invader or resident, barbarian or civilised myself.

Links:

- There is a useful, well-illustrated account of Rochester castle and its walls at the CastlesFortsBattles site

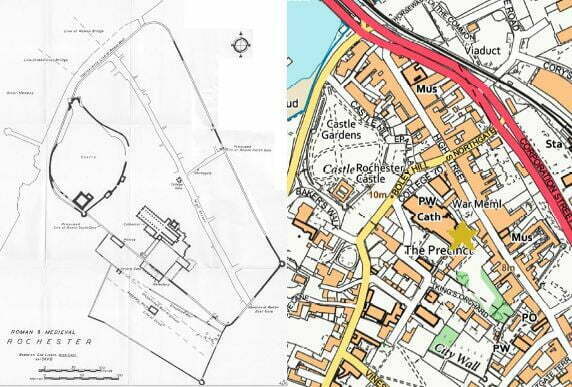

- The journal Archaeologia Cantiana has published a number of articles on the walls of Rochester. A.C. Harrison and Colin Flight, ‘The Roman and Medieval Defences of Rochester in the Light of Recent Excavations‘, Archaeologia Cantiana, Vol. 83 (1968) has the map of the surviving walls used here. The full run of the journal (up to three years ago) is on the Kent Archaeological Society site (see Gatehouse gazetteer for links to the walls articles and other online writings)

- Kent County Council’s Exploring Kent’s Past site has technical details of the surviving Rochester walls with maps

- The interview with Guildhall Museum curator Steve Nye is on Walled Worlds, a blog about the Medway area of Kent and its walls

- Wikipedia has a list of some of the current border barriers around the world