I read quite a few books in 2020, and finished most of them. As with last year, rather than try and survey them all (which would be too much) or even just the ones I thought were good (which would still be too much), I have selected twelve, one for each of the months in which – roughly speaking – I read it. Again, as with last year, each is picture with the drink that accompanied on reading sessions (anyone diverted by this can discover more on my Flickr album and hashtag #thebookimreadingthedrinkimdrinking).

January. The first book I read in 2020 was the best new book I read all year. Shadow City: A Woman Walks Kabul, by Taran N. Khan is a guide to a place like no other, not least because Kabul is a city like no other. Khan, an Indian journalist of Pashtun descent, recounts several visits to the city through which she walks, figuratively and mentally, exploring the city through its different layers of history. It weaves together the past and present, myth and reality in an extraordinarily vivid way. There is no escaping the hazards of walking through such a city riven with such conflict, and for a woman too (“I see walking as a luxury, not as something to be taken for granted”), yet one also gets a clear sense pf the day-to-day living of the place beyond what screens show us. There is a pivotal chapter featuring a visit to the archive at the state film body Afghan Film, where she sees newsreels and documentaries with their “particular ways of forgetting that defines remembering in Kabul”. It is a singularly haunting book.

February. I had long wanted to read The Sioux, a 1965 novel by the film actress Irene Handl. Just reading about it seemed fantastical – a lush, exotic story of an aristocratic French family, revered by those critics who weren’t completely puzzled by it, coming from the pen of Mrs Kite and all those other working-class wives, landladies, and English eccentrics with which she graced she screen for so many years. But it would be an astonishing book from any pen. Its rococo telling (the manner may owe something to Ronald Firbank) of a few incidents in the lives of the impossibly self-centred Benoit family (‘the Sioux’) becomes all the more compelling – and alarming – because the author seems as entranced as she is appalled by her creation. This takes the book occasionally into dark territory (the Benoits’ racial views and plantation heritage might mean the book would get a different reception if published today). I can’t say that I liked it as such; I was just continually amazed. Reading it is like drowning in a cocktail.

March. American essayist and cultural Lewis Hyde’s A Primer for Forgetting is a book about getting over the past. It is a collection of fragments with commentary: some of them passages from books, some of them accounts by the author, some of them images, arranged to support the idea of forgetting as a blessing rather than something to be feared. It is built on a paradox, since for every piece from a classical author on the theme of forgetting, there are painful memories from history (the book becomes overpowering its its account of lynching and the Ku Klux Klan) which Hyde wants to be remembered first before any healing through the processing of forgetting might begin. Each of the book’s sections is prefaced by a set of aphorisms, and the first of these, “Every act of memory is an act of forgetting”, resolves the paradox. It’s a book for reading in fragments, and it can be overbearing in places, but there is something impossible to forget on almost every page.

April. You can’t go wrong with James Shapiro. He is the epitome of the entirely reliable writer. His subject is Shakespeare (1599, 1606, Contested Will) and he combines encyclopedic knowledge with a gift for narrative and a compulsive belief in his subject. You know what you are going to get with a new Shapiro book, and you are grateful for it. Shakespeare in a Divided America does exactly that – viewing the political and cultural tensions that have been tearing the country apart, through the prism of two hundred years of Shakespearean performance. “At first glance it seems almost perverse,” he writes, “that Americans would choose to make essential to their classrooms and theaters a writer whose works enact some of their darkest nightmares or most lurid fantasies: a black man marrying then killing a white woman; a Jew threatening to cut a pound of a Christian’s flesh; the brutal assassination of a ruler deemed tyrannical; the taming of a wife who defies male authority”. Well, of course, not every American goes to the theatre or pays attention in English classes, and at times Shapiro doth protest too much. Shakespeare has healed many an individual, but never I think a whole society. But Shapiro does write so very well.

May. The Austrian writer Christoph Ransmayr was my great discovery of 2019. His philosophical travel book, Atlas of an Anxious Man, a work vastly better than its title might suggest, is one of the finest books I have read. I have been working my way through his other books, which are uneven but never less than confounding – Ransmayr is someone who, presented with a choice of two paths, will always walk down the third. His 1990 novel The Last World received much acclaim on publication and ought to be recognised as a modern classic, yet it has been allowed to slip into obscurity. Perhaps its strangeness is a little too unsettling. The backbone of the story is the exile of the poet Ovid on the shores of the Black Sea, banished for having offended the emperor Augustus in some way. It is a fine theme for a conventional work, but Ransmayr’s ancient world is bizarre – there are buses, the town sees a film show, guns are fired. People, places and time itself all undergo strange change. The key to the mystery is metamorphosis: Ovid’s Metamorphoses, to be exact, characters from which find their parallels in Ransmayr’s book, as explained in an appendix that makes you want to start the book all over again, now that you have found the key. It is Ovid’s novel, in the end.

June. I have read most of V.S. Naipaul’s books over the years (I started young); The Loss of El Dorado was one that remained on the ‘to do’ list, biding its time. It is a strange work. Ostensibly it is a history, focussed on two stages in the development of Trinidad, where Naipaul was born. One is the end of the search for El Dorado in the early 1600s; the other, from two hundred years later, comes from the island’s time as a British slave colony, focussed on the dreadful treatment of the teenager Luisa Calderon, victim of the unspeakable Thomas Picton, who survived his British trial for the use of torture and went on to be a war hero, dying at Waterloo. St Paul’s is now presumably deeply embarrassment by the monument raised to Picton that has pride of place in the cathedral. Naipaul’s book is scrupulously researched, yet is like no history book that I can think of. Elliptical, selective, in some places barely comprehensible, you can’t imagine any historian wanting to cite it, yet none would fail to be stirred by it. It is an experiment that does not entirely work, yet one cannot imagine quite what the successful application of such a novelist’s history would look like.

July. Julia Blackburn is a writer whose works always surprise but always please. She takes on wildly varied topics, from Goya, to Napoleon on St Helena, to Billie Holiday, to Norfolk fisherman-turned-embroiderer John Craske. Time Song is about Doggerland, the land that once stood between Britain and the Netherlands, until the rising seas swamped it seven thousand years ago. It’s a personal quest for what is lost as much as an archaeological investigation, and with the chapters interspersed with poems (‘time songs’) on the meanings and processes of archaeology, it could have been all too self-indulgent. It is anything but. Impeccably written, it is haunted by the ghosts of those people who once lived on Doggerland, the outline of whose footsteps have been found off the Suffolk shore (where Blackburn lives), utterly fragile survivals from a lost world. As one of the experts Blackburn consults tells her, “archaeology is an act of remembrance, even if you are remembering things you never consciously knew”. That is exactly the effect of her book.

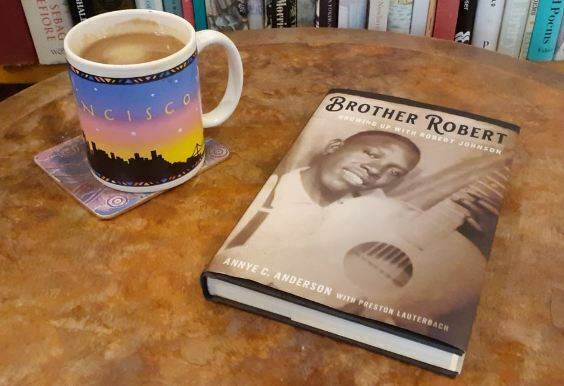

August. Here was a book, and here was a cover photograph, that you just could not have expected. Robert Johnson is the legendary bluesman of the 1930s, who died (probably murdered) in 1938, aged just twenty-seven, leaving twenty-nine songs behind him, whose influence on popular music has been immense. So little known about for years, Johnson seemed more myth than reality, until scraps of biography started to emerge, then one photograph, then a second. Yet still he was mystery, an emblematic figure onto which almost any fantasy might be attached. Then this year his step-sister Annye C. Anderson came out of the shadows, with a third photograph and an account of the young man she knew (she was twelve when he died). Brother Robert makes the myth human without losing any of his otherworldly greatness. Even if you care nothing for Johnson’s music (what’s wrong with you?), it is a detailed, lively and wholly convincing account of black lives in Memphis that should entrance anyone. Just to know that Johnson sang nursery rhymes for children and that he liked Gene Autry westerns is a thrill. He seems to have been everything a twelve-year-old girl would want in an older brother. A lot of the book is about battles with lawyers to protect Johnson’s legacy, but these only make you admire her all the more, for her tenacity. The spikey Anderson is nobody’s pushover, but co-writer Preston Lauterbach has patiently extracted from her a peach of a memoir.

September. The finest book I read all year has one of the dullest of titles. Journal of Researches is now much better known as The Voyage of the Beagle, Charles Darwin’s account of the round-the-world trip he took 1831-1835 (when it started he was twenty-two), visiting South America, the Galapagos islands, Tahiti, New Zealand and Australia, during which he gathered evidence and formulated ideas that would eventually lead to his theory of evolution. Originally published as part of a four-volume set on the voyages of the Beagle, Darwin’s account proved so popular that it was published separately as Journal of Researches. Its popularity is no surprise. Darwin is incapable of making a dull observation. Though he writes as much about geology as he does about animal life, and though much of the book involves travel through some of the drabber regions of Argentina and Chile, Darwin sees and communicates richness in everything. He revels (politely) in his observational skills, time and time again analysing a landscape or natural phenomenon with logical insight. There may be occasional gentle ribbing of some of his scientific peers who had not looked so closely at things as he, but overall the reader is simply thrilled at the sense of a world made clear. Book and man are in every way prodigious.

October. Marilynne Robinson has become an institution in the USA for her quartet of novels about the white Ames and Boughton families, whose lives are steeped in Congregationalist religion, through which the protagonists try to rationalise and tolerate life’s vicissitudes (her first novel was Housekeeping, subsequently turned into a sublime film by Bill Forsyth). She has developed a literary style than is entirely her own, religiously inflected, filled with sorrow, like a prayer book in dispute with itself. Jack completes the quartet by giving us the background story of the troubled Jack Boughton, whose disgrace after he abandons a young woman he has seduced forms the backbone of the first novel, Gilead. Here he find salvation in his love for black teacher Delia Miles, a relationship whose redemptiveness is before its time, given the prejudices (and laws) against mixed-marriage in 1950s America. It will be too theological for some, and Delia’s character is not as developed as it might be, but page for page there is little else like it – except for Robinson’s other novels, that is.

November. In 2018 I went to the mid-Atlantic island of St Helena, the realisation of a forty-year dream. When there I learned about Fernão Lopes, the first inhabitant of the island, a Portuguese soldier of the sixteenth century who underwent an extraordinary conversion to Islam while stationed in Goa, was captured and mutilated by his former Christian patron, then hid himself on the island of St Helena when a ship was taking him back to Portugal. There he lived alone for thirty years, becoming famous, even revered for his hermit-like isolation. There was one trip to Lisbon (and possibly Rome), but he returned to the island. He became a changed man, though one whose mysteries remained with himself. I wrote a blog post about him. One Abdul Azzam added a comment, saying that I might like to read his book about Lopes. This year I did. It is called The Other Exile, and it is a first-rate piece of investigation into history and motivation. It is gripping in its early accounts of the Portuguese empire building in India (Azzam is careful to show us as much the Indian side as the traditional aggrandizing Portuguese accounts of these wars). It then becomes stimulating in its speculation on Lopes’s religious conversation and spiritual journey that found some sort of realisation on St Helena. Some of the speculation is built on slender evidence (was Lopes Jewish? – there seems nothing to suggest it), but Azzam acknowledges this. Lopes’s life has the same quality of myth that we see in Robinson Crusoe. His story should be famous, and it could hardly be better told than it is here.

December. The Irish poet Derek Mahon, whose work I have cherished since university days, died in October. He had just completed this collection of poems, Washing Up, which has been published posthumously. Mahon’s latter work has not always been his strongest, with a bit too much complaining about all that is modern. Washing Up has quite a few poems that continue in this vein, but also several that are singularly graceful and memorable. There are seven exquisite twelve-line poems, collectively entitled ‘b/w’, on black and white films (Brighton Rock, Wild Strawberries, A bout de souffle) that are as finely-observed pieces of the poetry of film as I have ever read (“Whatever about the lurid twentieth century / I quickly recognise that bleak country, / the squinting windows and harsh oversight / that always saw the world in black and white”, he writes of Effie Briest). Best of all are poems of kindness to others: to children who will inherit a world very different to the one he knows (‘The Old Place’), to local amateur actors inhabiting their characters (‘Chekhov at the Grove’) and my favourite,’Smoky Quartz’, in which he says thank you for someone’s gift of a healing crystal. One might expect this to drive a cynic like Mahon to scorn, but instead he shapes act and gift into something greatly touching – but with his habitual sharp eye for surprise:

It’s a mysterious thing, transparent and opaque

like life, with faint patches of yellow light

moving around, though mostly it’s black smoke

as if from buses burning at a riot,

a crippled oil rig or the world at night.

There are poems on the coronavirus (including ‘Around the House’, a paean to the re-discovery of home), some tirades at artists who do not fight as they should (‘A Line of Moore’) and reflections on the ending of things (‘An Old Theme’), from a writer aware that each poem written might be his last. Its overall theme is that poetry matters. It makes the case well.

Fascinating how one man’s journey through the reading year can be so different. Much of mine spent reading books that had long languished on the shelves. But two points of contact with your list. I read Darwin’s Journal while travelling around the Galapagos Islands several years ago and agree completely with your praise. I was also saddened to hear of Derek Mahon’s death. Although I lost touch with his later writing, I published some of the early work back in the 60s in Belfast. And he wrote one great poem about the suburb where I grew up: Glengormley. Happy reading in 2021!

Ian,

Thank you as always. I shall get to the Galapagos islands one day. But you must tell me more about your connection with Derek Mahon – I did not know. ‘Glengormley’ is a favourite

Next year I shall read only books that have languished too long on the shelves, in strict order of length of languishment.