I have been having an online discussion with a couple of journalists about newsreels of the Empire Windrush and the arrival of West Indians at Tilbury Docks on 21 June 1948. A Pathé newsreel has been repeatedly used in news programmes and documentaries, and has been widely shared on social media. The conversation brought up some interesting issues about how we understand news archives from a modern perspective. I felt it would be useful to provide a history of how the Windrush story was filmed. So here it is.

The passenger liner HMT Empire Windrush brought one of the first substantial groups of West Indian immigrants to the UK on 21 June 1948. Of the 1,027 passengers (and two stowaways), 802 had come from the Caribbean, most hoping to find employment following news of labour shortages in the UK, with an intention to settle.

The arrival of these new black Britons has gained great symbolic significance, with its 70th anniversary last year being the subject of considerable interest and some political fall-out last year, after some of the so-called ‘Windrush generation’ were threatened with deportation, an unintended consequence of a change in the UK’s immigration laws. It was a news story back in 1948 as well, but how much of a news story?

Newspapers

In 1948 there were four primary ways in which news was published in the UK. The first was newspapers. At this time there were nine daily national titles – in descending order of popularity The Daily Express, Daily Mirror, Daily Mail, Daily Herald, News Chronicle, Daily Telegraph, Daily Graphic, The Times and The Daily Worker – and nine Sunday titles – again in descending order of readership, The News of the World, The People, The Sunday Pictorial, The Sunday Express, The Sunday Dispatch, The Sunday Graphic, Reynolds News, The Sunday Times and The Observer. The 1948 Hulton Readership survey found that 87% of the adult population read a daily newspaper, and 92% read a Sunday newspaper. Newspapers made the news.

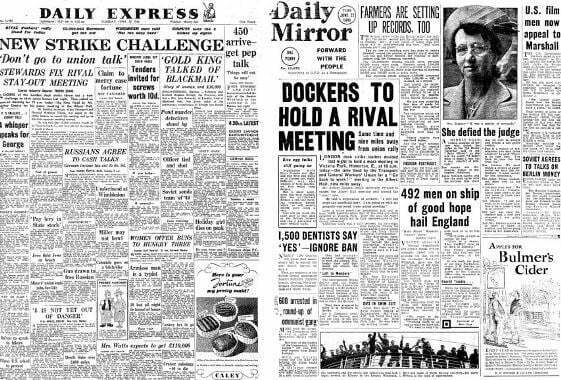

The story was widely covered, but not as prominently as might be expected. The top two titles put it on their front page, but for the Daily Express, the story ‘450 Arrive – Get Pep Talk’ had to compete with over twenty other stories on the broadsheet page. Its focus is on the unpreparedness of the Colonial Office, and the lecture the arrivals were given by an official on how things would not be as easy for those seeking work as they might have imagined. The Daily Mirror had a brighter headline, ‘492 Men on Ship of Good Hope Hail England’, but likewise focussed on the difference between hopes and reality. It quoted discouraging words given to the arrivals by an RAF Welfare Officer, including the admonition “No slackers will be tolerated”. The most widely-read newspapers reflected official disquiet over the very idea of letting people from the West Indies into the UK (despite the recent British Nationality Act which had defined British citizenship in global i.e. Commonwealth terms). That said, the Daily Mail had a welcoming tone to its 22 June story, ‘Cheers for Men from Jamaica’, describing the operation as being ’emigration-in-reverse’ (but it was on page 3, not the front page).

Radio

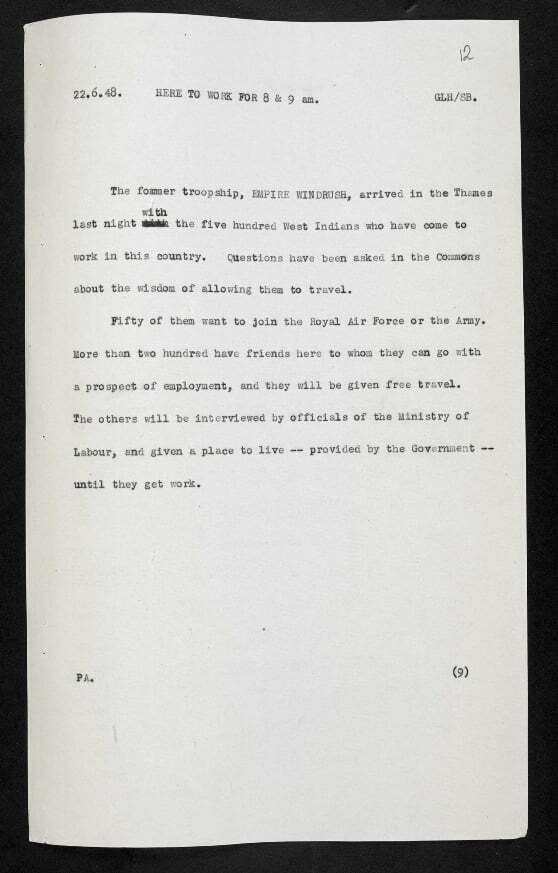

Then there was radio, which meant the BBC, whose Home Service broadcast six news bulletins a day, reaching a huge audience – there were over 11 million radio licences held in the UK in 1948. The BBC radio bulletin, the various versions of which throughout the day survive as scripts, though mostly matter of fact about the numbers and arrangements, notes as do the newspapers the concerns that were being raised by some in government. “Questions have been asked in the Commons about the wisdom of allowing them to travel” it reports. The BBC bulletin aspired towards the neutral, but in following the party line could not avoid the tone of official suspicion.

Newsreels

Thirdly, there was the newsreels. It might seem extraordinary to some now that people ever saw the news in cinemas, but the immediate post-war period, when cinemagoing was at its peak in the UK (there were 1,635,000,000 cinema admissions in 1946), practically every one of the UK’s 4,500 cinemas showed a newsreel as part of its programme. There were some dedicated newsreel cinemas as well, which showed just newsreels, cartoons and travel films, mostly found in big cities. Newspapers and radio were dominant, but newsreels were nevertheless played a major part in building up people’s picture of the news.

That idea of ‘building up’ is an important one. Much as we pick up our idea of the news today from different media – mostly online or on TV, with newspapers of diminishing importance – so it was with a different balance of media in 1948. The newsreels were not able to be issued as frequently as newspapers or radio because they were made on film, which took time to develop, edit and distribute. The newsreels were issued twice a week – that is, they produced a new issue on Mondays and Thursdays (so if you happened to go the cinema daily for some reason, you would have seen the same news for three or four days). This matched the usual public habit of going to the cinema twice a week. It meant that the newsreels often showed stories that people already knew about from the papers or the radio. What the newsreels could do was provide moving pictures. They didn’t tell the whole story; they filled out the story.

There were five newsreels in the UK in 1948 – British Movietone News, British Paramount News, Gaumont-British News, Pathé News and Universal News. So, as with newspapers, but not radio, not everyone saw the same newsreel. Often the five newsreels covered the same story, but that wasn’t the case with the Windrush arrivals. Two of the newsreels, British Movietone and British Paramount, did not bother.

Why was this? It’s hard to say for sure, but the likeliest answer is that it wasn’t seen as that big a story. It had had some coverage in the newspapers, but it was hardly a huge event, and the newsreels were as much in the entertainment business as they were in the news business. They selected stories for their visual interest and novelty as much as their currency.

It is interesting to see what stories each of the five British newsreels covered for Thursday 24 June 1948, the first release date after the Windrush story took place (21 June). We can see this from their issue records on the News on Screen database:

British Movietone News, issue no. 994A

Wimbledon Opens

Beauty on Water Skis

Upsets Mar Soap-Box Derby

The Queen Starts the Marathon

And Sees Model Planes Fly

Sweden’s King is 90 Years Old

Palestine – The Truce

British Paramount News, issue no. 1807

Jews and Arabs Observe Truce in Palestine

Wimbledon Tennis Stars Get Going

News from the Junior Front: Children’s Dog Show in Hyde Park

News from the Junior Front: World’s Smallest Dog

News from the Junior Front: Soap Box Derby in Germany

Western Germans Get New Currency

Veteran of Forty Wins Twenty-Six-Mile Marathon

Gaumont-British News, issue no. 1510

Opening of the Wimbledon Championships

Thrills and Spills on Land and Water

Roving Camera Reports: King Gustav’s 90th Birthday

Roving Camera Reports: Palestine Truce

Roving Camera Reports: Jamaicans Arrive

Marathon Race Started by the Queen

Pathé News, issue no. 48/51

Queen Starts Marathon

Druids Hail the Dawn

Mayor Gives Chopstick Lunch

Abdullah Worships in Jerusalem

Pathe Reporter Meets [Ingrid Bergman interviewed by film director Alfred Hitchcock on her arrival at Heathrow]

Pathe Reporter Meets [Jamaicans come to Britain to look for work. Interviewed by Pathe Reporter]

Universal News, issue no. 1872

Open Air Art Exhibition

News in Brief [safety devices]

News in Brief [Belgium – canoes ‘shoot the rapids’]

News in Brief [Monsieur Spaak’s daughter weds]

News in Brief [Mr and Mrs Attlee visit ‘Surrey Hills Clinic’]

News in Brief [Germany – Boy’s soap box race]

News in Brief [Children’s dog show in London]

News in Brief [Polytechnic marathon at Windsor]

News in Brief [Jamaicans arrive for work in England]

Lawn Tennis Championships at Wimbledon

So there were three newsreel reports on Windrush. One of them, produced by Universal News, does not survive in the archives, but it was quite probably the same footage as featured in Gaumont-British News because the two newsreels were both part of the Rank film company and co-operated closely. Therefore we have two newsreel films available to us. Happily both can be seen online.

‘Pathe Reporter Meets’, Pathé News issue 48/51, 24 June 1948 (the Windrush item is preceded by an interview with film star Ingrid Bergman and Alfred Hitchcock)

The most significant, and the most widely-seen today, is that produced by Pathé News. It is a fabulous film. The West Indian young men come across as engaging and earnest, radiating an optimism that makes you want to cross somehow into the screen and shake their hands. It culminates in calypso singer Lord Kitchener (real name Aldwyn Roberts) singing an acapella ode to his new home, ‘London is the Place for Me‘. The commentary (by Pathé stalwart Bob Danvers-Walker) is notable for its positivity, which would be a characteristic of British newsreel coverage of West Indian immigration over the next few years. There is reference to the less than kind reception that was in the minds of some in government, which Danvers-Walker pointedly counters by stressing public favour, reminding the audience of their best intentions: “prodded by public opinion, the Colonial Office gives them a more cordial welcome than was at first envisaged”. The difference in tone to that adopted by newspapers and radio is notable.

The bright spirit of the film is aided greatly by the interviewer, John Parsons. His presence makes the newsreel story come across as more recognisable to us, as we are used to reporters asking questions before the camera. In 1948, however, this was a radical approach. Parsons was a former army officer who in 1947 had recruited by Pathé’s forward-thinking boss Howard Thomas to bring a new personal touch to the newsreel. On-screen reporters were seldom seen in the newsreels, which generally relied on a unseen commentator speaking over the musical background. Pathé’s experiment was admired, but not adopted widely until television news as we understand it, with a presenter and reporter inserts, took off in 1955. The Pathé News report on the Windrush arrivals is therefore atypical of the average newsreel, but does show a medium that saw the need to develop.

That need to develop was recognised by the Pathé editor of the time, G. Clement Cave. He was keen to see the newsreel address social and political issues, setting aside some of the trivial filler material which had diminished the newsreel as a source of news in the eyes of critics. The Windrush story could be seen as one manifestation of this policy, though when it was released Clement Cave had been relegated to news editor after more overtly political coverage that analysed the background to topical stories had caused adverse comment from audiences and exhibitors. Newsreels were obliged to be politically cautious. They were a part of the cinema programme, but occupied only a small part of that programme – 10 minutes out of a show of three hours or more meant that they lacked sufficient muscle to be more challenging. Where they were shown determined their whole approach to the news.

We know more about how the Windrush newsreel was produced from the surviving paperwork. The shotlist report submitted by the camera operators gives their names: Cedric Baynes and John Rudkin. The fact that there were two camera operators, alongside the reporter Parsons, indicates that this was a story that Pathé saw as being important. The average newsreel story usually had one camera operator and often no live sound. Money was spent on ‘Pathe Reporter Meets’ to give the story what they felt it merited. It was constructed to make an impact.

The other newsreel film that survives is more perfunctory. Gaumont-British News could usually be relied upon for interesting coverage with smart commentary, but ‘Roving Camera Reports Jamaicans Arrive‘, from issue no. 1510, released 24 June 1948, gives us a mere snapshot. There is just enough space for commentator Ted Emmett to tell us that these ‘400 happy Jamaicans’ are here to help the Motherland – “so let’s make them very welcome” – and it is all over in twenty seconds. It would be an error, however, to judge a newsreel story only by its length. The Pathé coverage is noteworthy for the extra effort put into its production, but newsreels often functioned as visual reminders of a story that already had news currency. It was presence, not duration, that was significant.

The newsreels, despite their positive tone, were no less selective in what they chose to tell than the other news media. They all refer to Jamaicans, though there were passengers from other parts of the Caribbean, plus Polish refugees who had come via Mexico. The pictures suggest that young men predominated, but there were over 250 adult women on board, and 86 children. Some had served in the RAF, but from the tone of the Pathé report you might think this applied to most of them (you sense Parsons’ approval in the tone of his questions). Any news story is selective: a story, in effect.

Television

There is one other film of the Windrush migrants. Fourth among the news media types that reported on the story was television. It was the minor medium, as there were only 112,000 TV licence holders at this time. The BBC, which was the only TV broadcaster in the country, had started broadcasting a bi-weekly news programme in January 1948, but it was unlike the news programmes we have today. Instead, BBC Television Newsreel was exactly like a cinema newsreel, with an unseen commentator and music playing over the stories. It was, in effect, a cinema product shown on the small screen.

It covered the story for its broadcast of 25 June 1948. Sandwiched between stories on druids celebrating the Summer Solstice and the ninetieth birthday celebrations of King Gustav of Sweden, ‘Jamaican Emigrants Arrive’ nevertheless follows Pathé in letting one the emigrants speak, though sadly the soundtrack is lost. The surviving mute two-minute film, held in the BBC archives, shows the Empire Windrush at Tilbury, with the emigrants on deck. One is interviewed by an unseen reporter, speaking into a large microphone. They gather up their luggage and proceed down a gangway. It is a witness, but little more.

Television news had started humbly, and with few viewers. But it would soon evolve, coming up with presenter-led, live programmes by 1955, with ITN offering the BBC keen competition. The millions moved from the cinema to the living room, and with that the newsreel, irredeemably out-dated, faded from our screens. The last Pathé News was released in February 1970.

What was different about the newsreel coverage of the Windrush migrants was not only its cordiality but how it was experienced. Newspapers, radio and television news were all consumed privately, or in a grouping no larger than a family. Newsreels, however, were seen in a cinema, where the viewer was joined by hundreds if not thousands of others. The newsreels understood that they were speaking to a crowd rather than an individual, which affected their whole tone of address. They spoke to a visible us.

This collective experience of news has been lost since the newsreels disappeared from British cinemas in the 1970s, but maybe there is some sort of inheritance in the way we read news on social media today. We each view our phone and computer screens as individuals, but we can follow the debate that a news story generates with an audience (mostly of our own choosing). We understand the news as something shared.

Despite this possible affinity with social media, there is much about the newsreels that will now seem strange. Some understanding of the conditions under which newsreels operated will, however, make them function once again for us as vital news forces. We are fortunate that so much of the British newsreel heritage is available on YouTube, including all of the British Movietone and Pathé newsreels, covering much of 20th century. The newsreels added something important to the news, and in Pathé’s report on Windrush we see the medium at its best. We feel ourselves to be part of that crowd, sharing in a news that was everyone’s news, a news that spoke to us all.

My thanks to Jake Berger and Andrew Martin at BBC Archive and Paul Wilson, radio curator at the British Library, for their help in producing this post

A version of this post is included in my book Let Me Dream Again: Essays on the Moving Image (Sticking Place Books, 2025)

Links:

- Records of British newsreel releases, with biographies of the people behind the newsreels, can be found on the News on Screen database, hosted by Learning on Screen

- The Pathé News newsreel is available on YouTube and on the British Pathé website. Though it had nothing to do with Pathé at the the time, the Gaumont-British News story can also be found on the British Pathé website

- The BBC radio news script on Windrush is reproduced on the British Library’ site. See also the British Library’s Windrush Stories microsite for much background information coming out of its 2018 exhibition

- There is much information on who was on the Windrush and how they broke down by gender, place of departure, skills and destination on the BBC News site

My book, Yesterday’s News: The British Cinema Newsreel Reader (2002), is probably the nearest we have to a history of the British newsreels. A proper study is long overdue.

A version of this blog post was published as ‘Filming Windrush‘ [PDF] in Representology, issue 5, Summer 2023, with a web version published on the Sir Lenny Henry Centre for Media Diversity site, 22 June 2023.