You led me into the trackless woods,

My falling stars, my dark endeavour.Anna Akhmatova, from ‘To My Poems’ (translated by Lyn Coffin)

What joy there is in coming across the great work of art that you had not been expecting. The writer new to you whose words say exactly what you had been, unknowingly, yearning to say. The painting discovered by idly browsing that abruptly makes you see the world anew. The film you had only chosen to watch because it was a dull day whose passion for life revives your own. The song playing in the background on the radio that turns out to have been written only for you. It is such moments that we should live for, like being surprised by love.

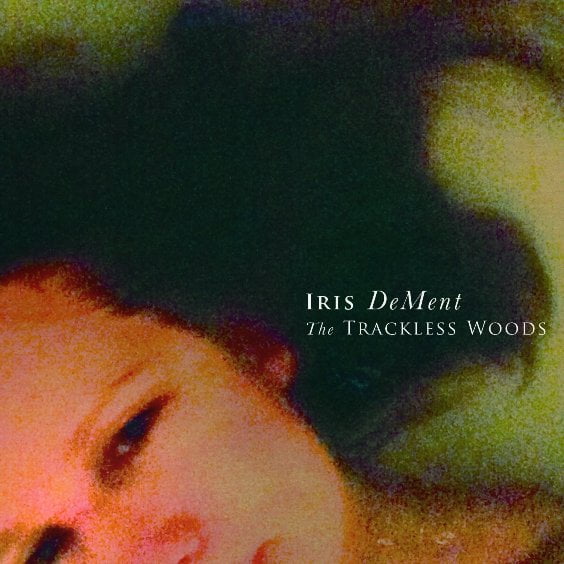

So it was that I was passing by a record shop (there are a few of them still out there), and picked up a CD by Iris DeMent entitled The Trackless Woods. I had come across her music last year when I started listening to some country music, inspired to do so by her singing on John Prine’s ribald ‘In Spite of Ourselves‘. I liked the bittersweet songs with their homely delivery on the albums I found on Spotify: Infamous Angel, My Life, The Way I Should. I had gone looking for one of these, but all I could find, tucked at the back of the row of plastic cases divided up by name labels was The Trackless Woods, not available on Spotify. Music by Iris DeMent, all texts by Anna Akhmatova, it said on the back. Hmm, not so sure about people trying to turn poems into songs, I thought. When does it ever work? But I thought I should support my local record shop, and so I took a punt. Back home, on a grey, blustery afternoon, I put on the music and picked up a book to read. And then I put the book down.

Iris DeMent singing ‘Listening to Singing’

Well, all those records previously lined up in my head in order of personal preference have had to shift along to make room for the newcomer, barging her way to the front. It is the most glorious, moving, creative set of music that I have heard in a long time. I don’t want to make converts to it – it matters not what others might think, and in any case I can find only the one sound file that to embed here to give any flavour of what I find so entrancing. For the record, it is a collection of songs based on the poem of the great Russian writer Anna Akhmatova, using English translations by Lyn Coffin and Babette Deutsch. The songs were recorded in DeMent’s living room, with herself playing piano and a small group of musicians (among them Leo Kottke on guitar). The effect is intentionally domestic yet equally with the rich sound one expects of a modern music recording. Despite the simplicity of the set-up, the instrumentation is subtly varied and the songs diverse in approach and tempo. What unites them is the harmony of two voices conjoined, that of American country-folk singer and Russian poet.

DeMent has a Russian daughter. She and her husband adopted her, from Siberia, in 2005, when she was six years old. Six years later, DeMent came across the poetry of Anna Akhmatova (1889-1966), one of the great figures of Russian poetry, who suffered so greatly under Stalin yet never lost her muse nor belief in her country. Her poetry is economical in expression, acute in thought and sentiment, yearning yet filled with the lessons of suffering. DeMent’s immediate sense of affinity led to a songwriter’s response: “Set that to music”. So she did.

It will burn you at the start

As if to breezes you were bare.

The drop deep into your heart

Like a single salty tear.Anna Akhmatova, from ‘Song of Songs’ (translator Babette Deutsch)

It ought not to work, having poems composed out of that mysterious combination of bleakness and lyricism which seems to characterise Russian (Soviet) poetry translated into the comforting tones of American country-folk. Instead it is an ideal agreement of opposites. The contrast accentuates the relationship. More is revealed than if the poems had been sung as Russian folk song; it is the surprise that concentrates the mind. Yet there is much that the two artists, though separated by time and half the globe, share. American poet David Biespiel, writing about The Trackless Woods, detects an affinity between the poet’s Russian preoccupations and the frequent subjects of DeMent’s country songs:

… [L]ike Akhmatova’s poems, DeMent’s songs depict people who exist not in the margins, but in the non-utopias of complex lives. They confront their own desperations and difficult joys, tensions and transformations.

The songs use Akhmatova’s poems in full, eighteen in total. The record concludes with a brief recording of the poet herself reading ‘The Muse’. The one exception is the set’s stand-out song, ‘The Souls of All My Dears’, which draw together lines from different poems and translations, while still coming across as a unified composition of shattering impact:

The souls of all my dears have flown to the stars

Thank god there’s no one left for me to lose.

It’s rare for poems to work as popular song. Once, back in Homeric days, there was no difference between poetry and song – poems were what you sang. But the two forms separated over time, and whenever they are brought back together again, questions arise over definition. Daniel Karlin, in his study of the idea of poetry as song, The Figure of the Singer (another happy, recent discovery), gives a pragmatic ruling: “A poem performed to music becomes a song, almost without an exception. A song lyric read aloud or on the page, however, does not always become a poem: you have to decide whether the element of music is necessary to its existence.”

That suggests much about the transformative effect of music, how it shapes that which it absorbs into its own form, because the ear homes in on the patterns in the sound. But though a poem sung may always become a song, that does not mean it will necessarily a good song, still less that the better the poem the better the song may be. Do not try singing ‘The Waste Land’, for example.

There is a long tradition in classical music of performing poetry as song, an exercise that I find mannered and cold and do not in any case have sufficient knowledge to saying anything useful about the results. But attempts by popular music to appropriate poetry are intriguing. There are of course the ‘real’ poets who make the crossover into song (Leonard Cohen, Tuli Kupferberg), those who hover between poetry and song (Gil Scott Heron, Linton Kwezi Johnson, Patti Smith) and those songwriters who are understood to be poetic in some form (Bob Dylan).

Those singers who have chosen to perform the poems of others are few, but the results are seldom less than intriguing, while the ingenuity required has demanded creativity. Among the interesting examples are Natalie Merchant’s folksy interpretation of Emily Dickinson’s ‘Because I Could Not Stop for Death‘; the Ravishing Beauties (Virginia Astley) singing Wilfred Owen’s ‘Futility‘ with a mournful sweetness; the Divine Comedy turning Wordsworth’s ‘Lucy‘ poems into ironic pop; Ladysmith Black Mambazo’s ingeniously reconstructed acapella version of Shakespeare’s sonnet no. 8, ‘Music to hear, why hearst thou music sadly‘; Van Morrison’s ambitious take on William Blake’s ‘America’ and ‘Vala: or the Four Zoas’, ‘Let the Slave‘; and most famously The Beatles’ lushly romantic ‘Golden Slumbers‘, a version of Thomas Dekker’s 1603 lullaby ‘Cradle Song’ (arguably a song rather than a poem).

There have been entire albums of poems reimagined as popular songs, but here the results have been patchy. What may work as an experimental one-off can be over-bearing as a collection. Interesting examples include The Waterboys’ heavy-handed but exuberant tribute to W.B. Yeats, An Appointment with Mr Yeats; Rufus Wainwright’s ambitious, semi-classical Take All My Loves – 9 Shakespearean Sonnets; and Joan Baez’s extraordinary combination of spoken and sung poetry, Baptism, which tackles Blake, Donne, Rimbaud, Lorca, Cummings and Owen, among others (a delicate interpretation of James Joyce’s ‘Ecce Puer/Of the Dark Past‘ may be the highlight). None, however, matches Iris DeMent for her insight, lack of pretension and ability to achieve cohesion with variety over the length of an album.

Why does almost every poem, when performed to music, become a song? Part of the answer lies in the choice – the singer will inevitably select song-like poems, sometimes surprising us by the skill with which they uncover that sing-able quality. It is a quality akin to translation (and of course Iris DeMent sings translations of Anna Akhmatova’s poetry), making an original work of art find new expression through a change of medium. But there is more to it than that. The trick must be to answer the urge the poet had that goes back to poetry’s roots, which is to sing out, to stop people in their tracks with a phrase and a melody. It is about expressing that which we will not want to forget. When poetry was sung, it was the practice that tales were committed to memory because few were written down. Song aided memory by being memorable.

This seems to be what makes The Trackless Woods the success that it is. Something about it recovers the poems’ inner song (several of those chosen by DeMent reference the idea of song, not accidentally). It is about committing to the heart that which is beguiling and memorable, that which can be shared and handed on, the key to the oral tradition (Anna Ahkmatova and others of her circle would memorise one another works during the height of Stalinist oppression, to avoid being incriminated by having anything written down). It is transmutation into familiarity. These are the songs, the poems, which, unknowingly, you have always known, the ones that turn out to have been written only for you.

And the power that propels the enchanted

Voice displays such hidden might.

It’s as if the grave were not ahead,

But mysterious stairs beginning their flight.Anna Akhmatova, from ‘Listening to Singing’ (translated by Lyn Coffin)

Links:

- The Trackless Woods is not available on Spotify, but its page on Amazon has sound clips for every track if you want to sample it [Update: the album is now available on Spotify

- David Biespeil’s informative analysis of DeMent’s songs and Akhmatova’s poetry and personal history, ‘Singer Iris DeMent’s Homage to Soviet Poet Anna Akhmatova‘, is on Bookforum.com

- There is an audio interview with Iris DeMent about her Akhmatova songs, with several clips from the album, on the Poetry Foundation site

Update (December 2019): Iris DeMent has put up the entire album on YouTube:

Update (October 2022): I have created a Spotify list of songs based on poems. Suggestions for additions are most welcome: