Few arguments can be more engrossing to take up, yet with so little hope of resolution, than the relationship between history and film. It is almost as if one of the chief functions of film is to bring history into confusion. Actuality film – newsreels, newsfilms, documentaries, home movies – appears to capture moments of historical time, and get re-used as the building blocks of historical documentaries. But the image of the event is not the event itself, while the presence of the camera brings its own influence to bear on what it is ostensibly recording. The more you look, the more uncertain you must become about what it is that you are looking at.

And as for the fiction film … so much has been written on the distortions of historical fact perpetrated by feature films and TV fiction where the imperative has been to tell a story and to entertain. Critics and historians have winced, wailed and wept at the heresies made by filmmakers. Many indulge, with a mixture of sadness and smugness, in the game of pointing out the most egregious examples. There are books devoted to the subject (Feature Films as History, Past Imperfect: Histories According to the Movies) and writers who have become specialists in this particular field (notably Robert Rosenstone, who became intrigued by the historical film’s paradoxes after working as a consultant on Reds).

Historians get employed by filmmakers, undoubtedly welcoming the pay cheques, but ultimately must cut sorry figures, as advice is overturned by expediency. The American Historical Association has these optimistic words in the careers section of its site, where it considers opportunities for consultants:

An increasingly sophisticated audience is demanding greater historical integrity in media productions. Producers of documentaries, dramatic films, and educational programming often hire historical consultants to advise on costumes, scenery, props, dialect, and content accuracy. Most television networks and large production companies will require the services of a historian …

Well, indeed they may, but the historian is there to advise and suggest, not to construct. History, to be told, must be subservient to the medium that expresses it. Film operates to the (perceived) logic of its audience. Historical truth must always bow to narrative necessity. If there is no story, there is no history.

I thought on these things while watching Mike Leigh’s new film, Peterloo, because it is a historical film unlike almost any other that I can recall. The film tells of the Peterloo Massacre, the famous – though not famous enough – incident in which a cavalry regiment charge a peaceful demonstration of some 60-70,000 people who had met at St Peter’s Field, Manchester, to protest over parliamentary representation. Eighteen people were killed, and hundreds wounded. It is a story that demands telling, though it is not one that has been filmed before now, to the best of my knowledge.

I enjoyed the film very much, both for what it tried to do and how it went about doing so. Firstly, though I’ve said that Peterloo is a story that demands telling, Peterloo the film does not tell a story. It appears to do, given that it follows a course of action that has its roots and their consequences, and it has characters whose fates intertwine. It shows a lesson learned through time, which is probably all that a story is. But what story exists is incidental to its purpose. That purpose is to produce an historical document.

Peterloo aims to be actuality, early 19th century newsreel if you will, the stuff that captures moments of historical time, from which one must then derive information from which to derive a history – which is the telling of a story. This is done most obviously through the scrupulous recreation of meetings and the speeches given at meetings, which we witness verbatim (albeit shortened from reality). The words people use, their means of expression, the clothes they wear, the way that they wear them, their habits and incidental manners (for example, people sitting up in bed to go to sleep), all aspects which offer nothing in themselves that will propel a story, all are foregrounded. We are so used to historical films and television programmes where the past is populated by twenty-first century people. They have the costumes of the past, but they think like us, talk like us, and share our preoccupations. In Peterloo we are not invited to recognise ourselves, even while it hopes that we must sympathize with the predicament of our ancestors. Of course Peterloo‘s recreation of the sounds, sights and manners of the past is not authentic (it is 200 years too late for that), but its efforts towards authenticity exist of themselves. They do not simply serve a story, to be distorted when the demands of story say that they must.

I called Peterloo a film by Mike Leigh (its writer and director) but it is really a Leigh and Riding film. Jacqueline Riding (who worked previously with Leigh on Mr Turner) is named high up the credits as ‘Historian’ (not the more usual ‘historical consultant’ that is found buried among the lesser credits of other films). If you read Riding’s complementary book, Peterloo: The Story of the Manchester Massacre, the parallels in technique between the two are remarkable. Riding collects evidence and presents it in good order. She pays particular attention to the look of things (we are told about the appearance of even the most minor of characters if she has the details to hand). It is scrupulous, a little pedantic, and it works well on film. She and Leigh have made an evidentiary historical film.

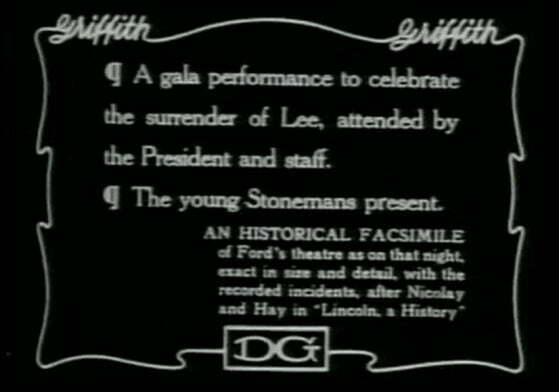

It is interesting to look at the history of historians and fiction films. It’s not a history that has been written, so far as I know, and except for recent years the evidence is not easy to find (as opposed to historians and actuality film, which is better documented). Historians were probably first involved, unwittingly, by D.W. Griffith, whose The Birth of Nation (1915) lays claim to historical veracity by citing various written histories or classic images in its intertitles. Perhaps the first historian to be involved in the production of a film was the British journalist and constitutional historian Sir Sidney Low, who wrote the scenario for The Life Story of David Lloyd George (UK 1918), converting very recent history into a feature film entertainment that likewise asserted veracity through the recreation of specific incidents. A notable early contribution was that of French historian Pierre Champion, who was hired as historical consultant for Carl Th. Dreyer’s La Passion de Jeanne d’Arc (France 1928), following Champion’s editing of the trial transcript of Joan of Arc in 1921.

For the classical years of Hollywood studio production, there must have been instances of where historians were called in to help verify (or justify) artistic decisions, but they seem little documented. There are some references to historical consultants, but invariably associated with documentaries, or drama-documentaries (the earliest I’ve traced is James T. Shotwell, historical consultant for Land of Liberty (USA 1939), a documentary on the history of the USA, edited by Cecil B. De Mille). Historical films were almost invariably adapted from novels, and if anyone was going to be consulted it was the novelist. There was little urge towards authenticity. It was the dream that mattered.

Things appear to have changed in the 1960s, as cinema itself changed with a new breed of filmmaker looking beyond the artifice of the studio era. One of the first historical consultants as we now understand them was Andrew Mollo. He was an authority of British military uniforms, who co-directed Kevin Brownlow’s alternative history about a Britain occupied by the Nazis, It Happened Here (UK 1964), after which he served as consultant on a number of popular war-themed films (e.g. The Eagle Has Landed) before joining Brownlow again for Winstanley (UK 1974), whose meticulous and profoundly sympathetic account of the proto-communist Diggers of the Civil War era, bears close affiliation with Peterloo. Brownlow and Mollo’s film also uses texts of the time, in the form of Gerrard Winstanley’s pamphlets, as foregrounding texts to which the images serve as verification, or commentary. Both pare away cinema’s decorative tendencies to present something like an unvarnished truth.

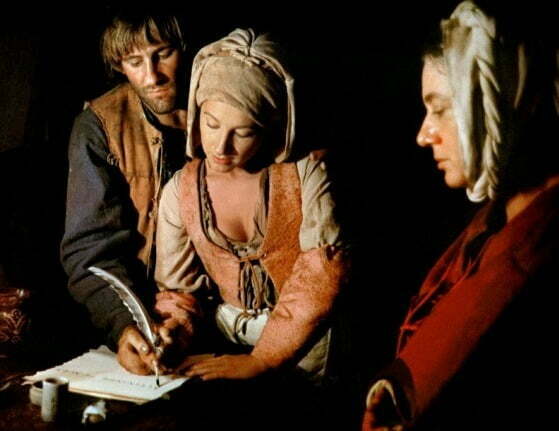

Probably the most celebrated example of a historian’s collaboration with a filmmaker is Natalie Zemon Davis and Le Retour de Martin Guerre / The Return of Martin Guerre (1982). Of this famous tale of imposture set in 16th-century French peasant life, Davis writes, “Rarely does a historian find so perfect a narrative structure in the events of the past with such dramatic popular appeal”. The story of Martin Guerre, the man who left his wife and child, then to be replaced by someone claiming to be him, only for the real Martin Guerre to return, is classically dramatic – even if it hinges on the unlikely hope that the audience will be in doubt, at least for a time, as to whether ‘Martin Guerre’ is telling the truth. It made for an entertaining film, directed by Daniel Vigne and featuring Gerard Depardieu and Nathalie Baye, weakened (ironically) by too heavy a reliance on that classical narrative structure. Perhaps for the medieval historian it is filled with small absurdities that would never be a part of French medieval life, but aside from some excusable lapses (everyone has perfect teeth and skin), it looks like the past come to life. It looks like the past inviting me to understand it.

The connection with Davis stands out because of her great reputation as a historian, and for her thoughtful writings on the experience of working closely on the film’s production (for which she was co-writer as well as historical consultant). As with Jacqueline Riding, she wrote a history book (The Return of Martin Guerre) that was published around the same time as the film (a year later, 1983). In the preface she writes:

Watching Gérard Depardieu feel his way into the role of the false Martin Guerre gave me new ways to think about the accomplishment of the real impostor, Arnaud du Tilh. I felt I had my own historical laboratory, generating not proofs, but historical possibilities. At the same time, the film was departing from the historical record, and I found this troubling. The Basque background of the Guerres was sacrificed; rural Protestantism was ignored; and especially the double game of the wife and the judge’s inner contradictions were softened. these changes may have helped to give the film the powerful simplicity that allowed the Martin Guerre story to become a legend in the first place, but they also made it hard to explain what actually happened. Where was there room in this beautiful and compelling cinematographic recreation of a village for the uncertainties, the ‘perhapses’, the ‘may-have-beens’, to which the historian has recourse when the evidence is inadequate or perplexing?

This anguish, partly a worry over cinema’s (apparent) simplifications, and partly a worry over the power of cinema to take stories beyond the control of the historian (particularly if you can call on actors of the calibre of Baye and Depardieu to enrich the telling), gets voiced again and again by the historical consultants of the modern era. Why have there been so many of them? It may have something to do with the emergence of videotape at around the time of The Return of Martin Guerre. Films which previously were seen only the cinema could now be rented. The details could be pored over, and failings – such as historical errors – more easily verified and shared. This went hand-in-hand with increased audience appetite for credible history, and was only accentuated by the arrival of the Web, which increased opportunities for anyone to analyse, discuss and share.

Now every film and television programme that looks to the past has an historical consultant. Not all are major names – the humblest professor for a university’s historical department is likely to have received the call asking to verify some turn of phrase, choice of costume or architectural construction. Some notable names have got involved, however. They include Robin Lane Fox (Alexander), Robert Lacey (The Queen, The Crown), Orlando Figes (Anna Karenina), and Kathleen Coleman (Gladiator), who was so disgusted with the results that she had her name taken off the credits (a despairing act undertaken by numerous other historical consultants). All report mixed experiences, arguing for a middle ground between authenticity of detail and truth to the spirit of the past. Robert Lacey’s comments on the ambiguities of historical authenticity making the Netflix series The Crown may sum it up best:

People say ‘is it true or is it false?’ … I say, ‘I don’t like the word false.’ I’d rather say is it true or is it invented? Is it true or is it imagined? Because, you see there is a difference between history and the past. The past is one thing. The past is what people lived through: lived and loved and betrayed each other and were true to each other. Most of the past vanishes. We don’t know the details.

Robert Rosenstone, the doyen of those who have studied the fiction film’s engagement with history, explains the difference between written history and filmed history, that seems to complement Lacey’s thoughts on history (something recreated) versus the past (something lost):

The world on the screen brings together things that, for analysis, or structural purposes, written history often has to split apart. Economics, politics, race, class and gender all come together in the lives and the moments of individuals, groups and nations. This characteristic of films throws into relief a certain convention – one might call it a fiction – of written history: the strategy that fractures the past into distinct topics, categories and chapters; that treats gender in one chapter, race in another, economy in a third.

Films must show what the written word alone cannot reveal. Films imagine. They do so by a process of synthesis, showing people caught in time, subject to process. They recreate events, they treasure any moments of authenticity that may be achieved, but they do not analyse as a historian must want to analyse. Instead they encourage identification with times past. They provide experience.

Peterloo has its limitations. It fails to show much in the way of suffering (the workers of Manchester do not seem to be leading a bad life, except for those unfortunate enough to get transported). The fear of a version of the French revolution occurring in Britain, that so animated those in power, is insufficiently explained. Thus the drivers behind the Peterloo Massacre are taken too much for granted. It has also been sold as the great entertainment film that it is not. The couple next to me in the cinema pronounced it to be the worst film they had ever seen (though they sat through all 154 minutes of it just to make sure).

Its greatest limitation is its great virtue. It boldly and beautifully tries to do what few historical films attempt, which is to be the evidence, forming its own kind of historical document. It can claim, with some confidence, to show us how things were, because of its integrity and because it allows nothing else to distract it from this purpose. It is the historian’s dream. But we, the audience, must dream of other things.