What are filmographies for? That might seems to be an easy question to answer – a filmography is a list of films defined by a particular subject, much as a bibliography is a similarly defined list of books. But that says what a filmography is; it doesn’t say what it is for.

It’s a question that has arisen recently with the publication of the BFI Filmography. This bills itself as being “the complete story of UK film 1911 to the present”, which it isn’t, since it restricts itself chiefly to fiction feature length films. It also boasts that it “compiles, for the very first time, a comprehensive list of UK feature films released to cinemas from the beginning of film history until now”, which is not true, since the late Denis Gifford first produced his The British Film Catalogue of British fiction films in 1973, updated it in 1985 and again in 2000, when he added a second volume for the non-fiction film.

Where the BFI Filmography is innovative is in how its data has been structured, and the use to which it has been put because of this structure. To understand why this is something new, it is necessary to look first at the history of the filmography. I’m not aware of any history of the filmography having been produced, and what follows is a random survey rather than the product of proper research.

The first filmographies were film company catalogues. In the earliest years of cinema, companies such as Lumière Frères, Georges Méliès’ Star-film and the Warwick Trading Company produced list of films that they were offering for sale, similar in structure to catalogues of photographs and lantern slides. The films were short, numerous, and identified by number and often a code word to aid bookings made by exhibitors, in the days before a fully-fledged distribution layer of the cinema industry emerged, which severed the direct link between producer and exhibitor. The films were usually arranged thematically (under subjects such as Military, Scenic, Sports etc). There was no presentation of the items chronologically, though this might be inferred from the numerical ordering, since films with a lower number tended to be those that had been filmed first.

Such catalogues, covering the early cinema period (to 1914), served a purely commercial need, though in their use of categorisation they served a basic analytical function. They did not provide credits, or only incidentally, but did impose consistency. Today they are greatly valued by film scholars, for whom they represent, collectively, the filmography of their era. A Lumière catalogue number is as important an identifier as is a Köchel number for the works of Mozart.

As films grew longer and the cinema programme became predominantly fictional, so the number of catalogues for the commercial film sector fell. But these proto-filmographies continued from 1920s onwards in the form of educational film catalogues, serving the burgeoning schools market using non-flammable 16mm. As with the early cinema period, the films were short, needed identifiers to aid ordering, and arranged the films by category for customer convenience. It was also educationalists who started producing lists of recommended films, demonstrating selection and purpose – A.P. Hollis’ Motion Pictures for Instruction (1926) is a fine example. At the same time, film studios had become dependent on vault lists to manage their growing collections. Films naturally lent themselves towards listing. They made sense through being associated with other films.

The shift from catalogue to filmography began with lists of great films produced by the new advocates of film art, notably the listing ‘The Production Units of Some Outstanding Films and Their Players’ given as an appendix in Paul Rotha’s The Film Till Now (1930). Such early attempts at creating a film canon influenced the collecting policies of the national film archives that appeared in the 1930s. They in turn started to issue lists of their holdings – the BFI’s National Film Library published its first such list in 1936, when it had 273 titles in its preservation section and 49 titles available for hire. These were purely functional lists, but what had driven the creation of national film archives (in the UK, USA, Germany and Belgium) was the imperative to preserve film as an art form. The impulse had changed, from commercial to cultural value. In 1951 the BFI produced the first selective list of its holdings, Silent News Films 1895-1933, following this up with Silent Non-Fiction Films 1895-1934 in 1960 (it never was able to produce a complete listing in print of its entire holdings).

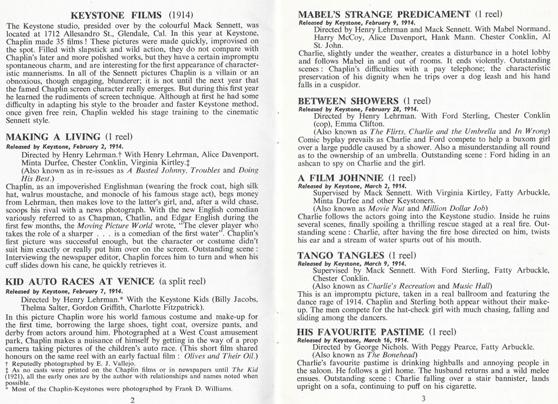

The word ‘filmography’ appears to date from around 1902, to judge from newspaper archives, when it was occasionally used over the new two decades to define the act of filming (there are 19th-century uses of the word in a photographic sense). In its modern definition the word, according to Merriam-Webster’s dictionary, may have been used first in 1941 (the Oxford English Dictionary gives its earliest appearance as 1962, which is when the term became common in its current sense). It was certainly in the 1940s that recognisable filmographies started to appear, focussing on particular film artists or aspects of film history. Notable early examples include An Index to the Films of Charles Chaplin by Theodore Huff, published by the BFI’s Sight and Sound magazine in 1945 as one of its pioneering ‘Index’ series of filmmaker lists, and Veniamin Vishnevskii’s Khudozhehestrennye fil’my dorevolyutsionn oi Rossii (1945), an epic filmography of pre-revolutionary Russian fiction films.

These new filmographies were archaeological (at a time when many of the primary sources were unknown or hard to locate), strove towards consistency and accuracy, and were intended to champion film as art, with an emphasis on its artists. The filmography was the product of a growing worldwide cinephilia movement, championing film for its own sake. Throughout the 1950s this led to the creation of film journals, festivals, film societies, and in the following decade to an explosion of book publications, hand in hand with the widespread acceptance of auteur theory. In such an environment, the filmography became for helping define a film artist’s worth. Notable filmographers have included Georges Sadoul (French cinema), Kemp Niver (early American film), Leonard Maltin (short films, American animation), Henri Bousquet (Pathé), John Barnes (Victorian cinema), Aldo Bernardini (Italian cinema), and Charles Musser (his Edison Motion Pictures, 1890-1900: An Annotated Filmography [1997] bids fair to be the greatest example of the filmographer’s art yet published). A significant percentage of the American publisher McFarland’s film-related output is filmographies. Nowadays, one cannot imagine a biography of a film director or cinema actor that does not include an filmography to confirm their artistic status – indeed it becomes a measure of the quality of such a study that it includes one.

Also at this time national filmographies started to appear. Some were the product of institutional imperatives, others the obsessive work of individuals. Probably the most notable was the American Film Institute’s documentation project, The American Film Institute Catalog of Motion Pictures. Launched in 1968, the project produced its first volume in 1971, covering American feature films 1921-1930. A volume for the 1960s appeared in 1976, and other decades have been published since (today the whole catalogue can be found online). The 1920s volume was relatively restricted in its ambitions, but subsequent volumes have greatly increased the amount of detail, notably the background references, historical notes and subject classification. The latter was among the AFI Catalog’s most significant innovations. Now one could review American film history analytically, extracting themes and elaborating on trends. Other great national filmographies, not so richly indexed but nevertheless the product of considerable historical investigation, include Zhongguo dianying fazhan shi [The History of the Development of Chinese Cinema] (1961), edited by Cheng Jihua, Li Shaobai and Xing Zuwen, and Andrew Pike and Ross Cooper’s Australian Film 1900-1977 (1980).

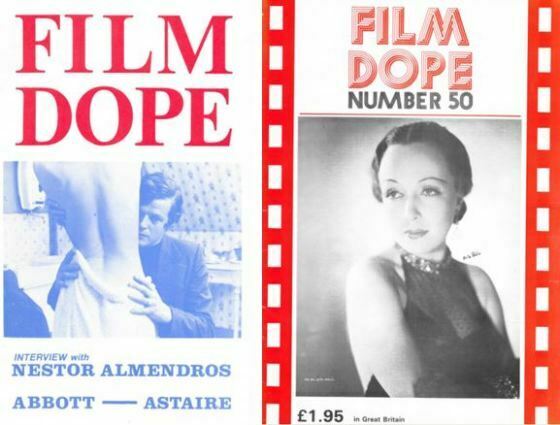

Among the private endeavours of note, Denis Gifford’s epic undertaking The British Film Catalogue has already been mentioned, but he produced other, smaller works of equal value and meticulousness, notably Entertainers in British Films and American Animated Films 1897-1929 (1990). The Swedish scholars Einar Lauritzen and Gunnar Lundquist produced the huge two-volume American Film-Index 1908-1915 (1998) and American Film-Index 1916-1920 in 1976 and 1984 respectively (an index to the two volumes was produced by Paul Spehr in 1996). The art of filmography as an expression of auterist faith probably reached it peak with the British journal Film Dope (1972-1994), which attempted to provide definitive lists of the films made by all of the world’s leading filmmakers, arranged alphabetically. The journal collapsed before the task could be completed (it reached the letter P), but it established a high standard for accuracy while restricting itself to simple lists of titles with dates followed by explanatory notes. One of Film Dope‘s chief contributors, Marrku Salmi, edited the peerless National Film Archive: Catalogue of Stills, Posters and Designs (1982), nothing but a list of titles, dates, directors and countries, but with an unmatched reliability of data.

Two national filmographies pointed towards future developments. In 1997 the AFI published Within Our Gates: Ethnicity in American Feature Films, 1911-1960, a special volumes in its Catalog series which covered films reflecting racial and national ethnic experience in the United States, crossing the decades to do so. Around the same time the Irish film scholar Kevin Rockett produced The Irish Filmography: Fiction Films 1896-1996 (1996), which documented not only Irish-produced film, but practically any film with an Irish element to it, rethinking the boundaries of his subject to make a political point. Such filmographies aimed not simply to document film history, but to challenge and change perceptions of it.

(I’m aware that I’m using the terms filmography, catalogue and database interchangeably. One could add encyclopedia as well, such as Phil Hardy’s fine Aurum Film Encyclopedias on Science Fiction, Westerns etc, which consist of descriptions films in those genres given chronologically. All are lists of films that fit a particular criterion, be that by person, subject, country, archive or whatever. All are filmographies, broadly speaking.)

The next great step in the history of filmographies was when they went online. The Internet Movie Database (IMBd) was founded in 1990 by British computer programmer Col Needham. It used fan power to build up the database, devotees enthusiastically (if not always accurately) documenting every corner of film history. Once fully established, greater controls were imposed over content creation, as the IMDb turned from being a finding tool to become a means by which the film industry measured itself. Its ranking features have made it a major determinant of film success, while the IMDbPro feature is widely used by those in the indsutry who want to add resumés, contact details etc. The filmography thereby became a part of the industry it recorded.

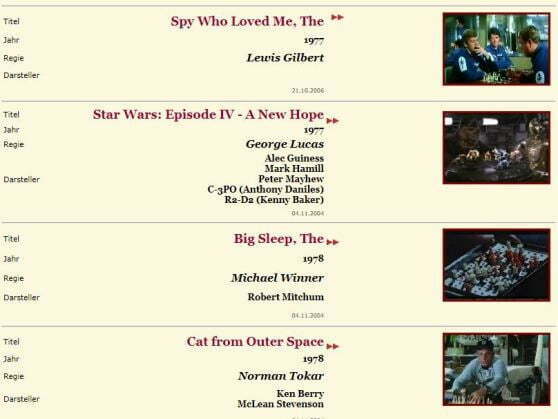

The IMDb was distinctive not only for its power, but for its range (all time periods and territories) and because it could be constantly updated. The updating aspect is one of the distinctive features of the online filmography – a boon because more can be added, a burden because there is no end to such work. Another is the diversity of such filmographies. While there are major, nationally-based online filmographies, such as Germany’s Filmportal and the Danish Film Database, the web has encouraged the creation of many filmographies that show film enthusiasm in all its many guises. Examples indicative of the diversity include Jazz on the Screen (originally a 1981 book by David Meeker), Librarians in the Movies, the alarming Internet Movie Firearms Database, or the exhaustive yet never-ending Chess in the Cinema.

The next step forward in the history of the filmography was a recent one. The Catalogue Lumière, which went live in 2013, is a database of the 1,428 films made by the Lumières 1895-1905, created by Manuel Schmalstieg out of the 1996 print publication La production cinématographique des Frères Lumière, edited by Michelle Aubert and Jean-Claude Seguin. This was the first filmography, to my knowledge, to be based on open data principles. There are some film-related APIs out there (i.e. application programme interfaces which allow you to harvest structured data from another source), while the IMDb offers subsets of its data to customers under licence. But a truly open database is not just lent but handed over. The Catalogue Lumière was designed for the sharing of the data in a form that lets others build on what the database holds. Users can download the catalogue listing in CSV format (CSV = comma separated values), and rebuild it, use it for data visualisations, or link it in whatever way to their own dataset. It is, to the best of my knowledge, the first freely reusable filmography.

All of which leads us on to the next stage of filmographies. The BFI Filmography weaponises film data. The filmography has been so structured that it allows any user to extract expected information, such as the number of feature films per year, the frequency of particular themes and genres, or the recurrence of characters, and to express such results as graphs or simple visualisations. So far so good – it’s a step on from the plain lists of the IMDb, or the useful but standard advanced search capabilities of the AFI Catalog. But, as the BFI’s Head of Data Stephen McConnachie writes, “the real power of the Filmography is in asking bigger and more serious questions with policy implications”.

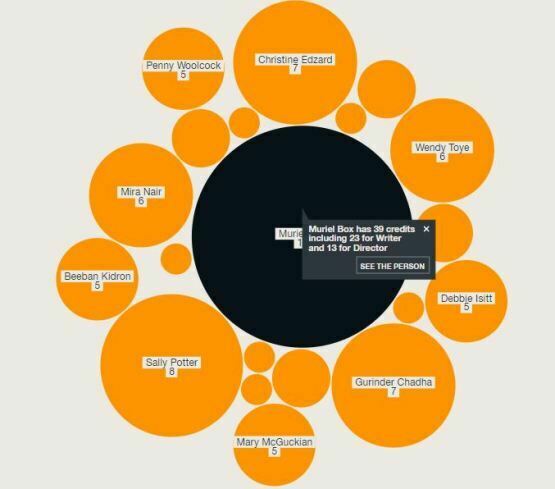

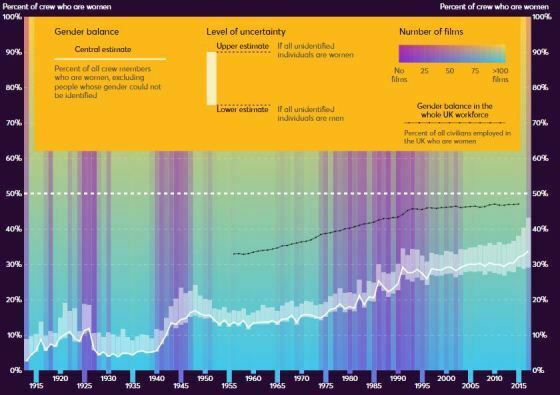

The filmography has been used to ask questions of the film world that generated it, demonstrating trends that may illustrate the industry’s shortcomings rather than simply its artistic worth. In particular the BFI Filmography has been used to analyse gender representation in British film. Matching gender (where known) to particular roles (director, scriptwriter, producer etc) and over periods of time, it has been used to examine such topics are the career longevity of women in the British film industry, the areas of filmmaking in which they have worked and how this has changed over time, their representation across the senior roles in film production, and in which films genres they are better represented.

The overall mission of this particular investigation has been to quantify gender imbalance, and thereby to promote change. It helps to have outsiders do your confirmation for you and the innovation foundation NESTA has commissioned a study, using the BFI data, ‘Women in film: what does the data say?‘, to analyse the raw evidence, with conclusions such as these:

- The gender mix in UK film casts has not improved since the end of the Second World War

- Female actors have tended to make fewer films and have had shorter careers than male actors

- Unnamed characters who work in high-skilled occupations (e.g. doctor) are much more likely to be portrayed by men than women

- Films that have one woman in a senior writing or directing role contain relatively more women in their casts

There is much that can be challenged about this sort of approach. It assumes that the roles, and the data overall, are consistent across time periods, when the truth is that the UK film industry in the 1910s, say, was greatly different to that of the 2010s (many more people work in films in 2010, for example). It makes no contextualising reference to employment trends outside of the film industry (though the NESTA study does incorporate these to a degree). But the claim to scientific veracity of data analysis always has a strong element of the bogus about it – all data queries are subjective, because you are looking for an answer to the question that you have posed. But the general trends and the overall imbalance are clear enough to see.

And so filmography impacts upon policy. The BFI is responsible for allotting Lottery funding to film production, distribution, education, audience development and market intelligence and research. Who can say how it may act upon such findings? At a time when the Harvey Weinstein news story is causing many to question the gender and power balance within the film industry that supported such attitudes, change through funding might well become a topic of discussion. And it will be the filmography that will provide the ammunition.

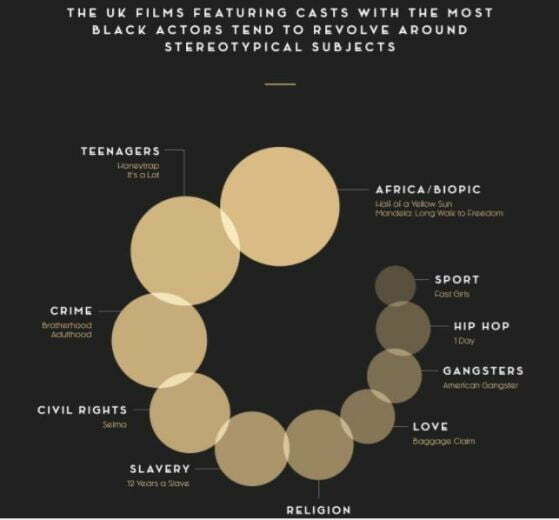

This is just the start of the use of the data. It will be used for traditional film history enquiries, of course (though it would help if the Filmography was more browsable in the traditional manner), but it will make its strongest mark where there are policy issues involved (the data has been used to investigate ethnicity in recent British film, for example).

The BFI clearly has further plans for its Filmography, and will issue these gradually. It is looking to develop more partnerships, such as the one with NESTA, and within academia – both film studies and the broader field of digital humanities. Further ahead, it is thinking about how digital methods such as speech-to-text and mood analysis could supply data to be overlaid on top of the core data structure. What they have done with their filmography is only the beginning.

The key point is that digital data is not enough in itself – it needs to answer questions, both old questions to which we need fresh responses, and questions that we hadn’t thought to, or been able to, ask before now. Filmographies have served the purposes of their times. Originally they were sales tools. Then they became expressions of a belief in film culture. Now they can be used to challenge what is privileged and what is suppressed within that culture. They can become a tool for change. That change is not simply through interpreting, and then acting upon, what film data tells us. The change lies also in making data open, shareable and linked to other kinds of data. It is about showing that film regains its proper purpose when it is connected to the outside world. Film as art has never been enough, and the data proves it.

Links:

- This is the BFI Filmography site: https://filmography.bfi.org.uk

- BFI Head of Data Stephen McConnachie provides an overview of the BFI filmography on the BFI’s website

- The NESTA analysis has been published as ‘Women in film: what does the data say?‘, with data visuslations on cast and crew

- I wrote an earlier blog post on film databases to be found online, from the extensive to the specialised, and in another post on the special value of the Catalogue Lumière

- And I’ve been known to produce a few filmographies myself. Here’s one from 1997, on Spanish Civil War films in the National Film and Television Archive

Bravo

Bravo to you too. Now someone needs to research the history of the filmography, properly. Anyone out there looking for a good PhD topic?

Great post, Luke. Unfortunately I’m excluded from the BFI Filmography. In a recent post – https://www.voyageuse.co.uk/a-hard-road/ I point to Stephen Follows research which indicates that the majority of UK feature films also fail to meet the criteria for inclusion in the BFI Filmography. Much work still to be done.

A hazard with online filmographies is that they can disappear. The BFI Filmography web page now has this message:

Sigh. It does note that the BFI’s Collections Database (a site I have used far more than the Filmography) remains online: https://collections-search.bfi.org.uk/web

Also, Chess in the Cinema has changed recently from a database to a blog about the topic, with the database itself no longer a part of the site. Happily the database as it was can still be found on the Internet Archive, here: https://web.archive.org/web/20220820033338/https://www.chess-in-the-cinema.de.

You wouldn’t get this with printed filmographies.