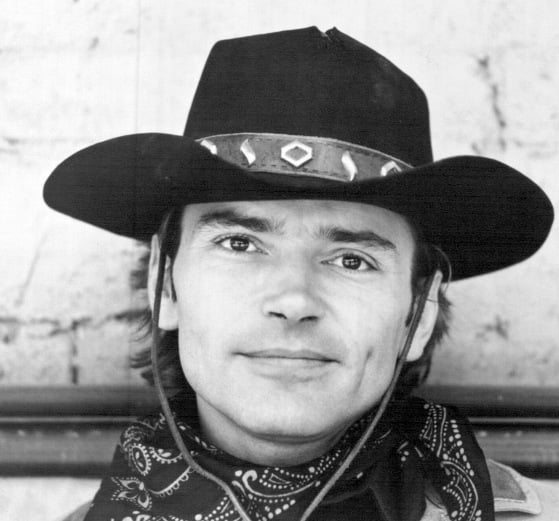

The first person of whose death I became aware was Pete Duel. He was an American actor, star of the popular television series Alias Smith and Jones, which followed the adventures of two outlaws in imitation of the film Butch Cassidy and the Sundance Kid. Duel committed suicide on the last day of 1971, and I remember the shock and the puzzlement that I felt. It was not so much that his life was lost but the realisation that he had had a separate life to the happy character of Hannibal Heyes that he played on the screen. His real life had been somewhere else, but equally a part of his life had been mine.

Thereafter I was greatly moved by the death of Marc Bolan, who was such a figurehead to those of my generation; was indifferent to the death of Elvis Presley, who I really only knew as a bad actor; and shocked as the whole world was at the murder of John Lennon. I didn’t know these people, but those whose passing I felt, mattered to me. It was not as though I knew them, or even felt that I knew them, but even so in some way I had lost their company.

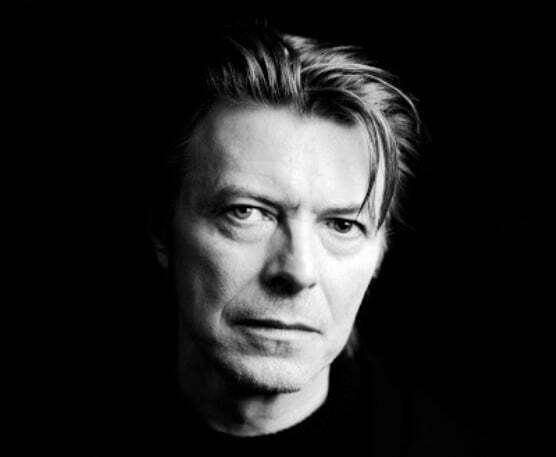

Years have gone by, and I have experienced deaths of friends and family, inevitably, and of many people I knew only through their fame. This week David Bowie died, and the worldwide outpouring of grief has been genuine, well merited, but also curious. So many people mourning a person they never met (or saw only in concert), indeed many mourning he whose golden years had taken place years before they were born. What was it that they were mourning?

Glen David Gold’s novel Sunnyside opens with a case of mass delusion in which Charlie Chaplin appears in eight hundred different places simultaneously. Supposedly based on a true case from November 1916, the conceit shows how an idea of the motion picture actor could be shared by many different people in a collective understanding that was nevertheless different for each individual. There was only one Charlie Chaplin, yet everyone felt they knew him – that they experienced him – in their own particular way.

There had been no one else like this previously in human history. Gerben Bakker, in his book Entertainment Industrialised, goes into the economics behind it:

When Charlie Chaplin was nineteen years old he appeared in three music halls a night. On one fine day he started in the late afternoon at the half-empty Streatham Empire in London. Directly after the show he and his company were rushed by private bus to the Canterbury Music Hall and then on to the Tivoli. This constituted the maximum number of venues an entertainer could visit on an evening, and thus the inherent limit to a performer’s productivity.

Yet, barely five years had passed before Chaplin would appear in thousands of venues across the world at the same time. His productivity had increased almost unimaginably.

Bakker is interested in the economics of Chaplin, how cinema prices were lower than those of music hall so that he could only capture of small percentage of revenues, yet nevertheless ended up as the world’s highest-paid performer. But the distribution of Chaplin enabled to him also to be shared in an emotional sense. People felt they knew Chaplin, Mary Pickford, John Bunny, Florence Lawrence, and the other first film stars of the 1910s. They increased people’s social circle. Previously most people knew very few people. They knew their own family, their neighbours and their work colleagues. They were constrained by a narrow social set. People had lived like this for centuries, knowing few others, who on the whole were only of interest because their were family, neighbours or work colleagues.

Cinema extended who you knew. You shared an intimacy with people who were glamorous, capable, versatile, popular and who seemed familiar even as they were utterly remote. The deaths of John Bunny (in 1915), Wallace Reid (1923) and Rudolph Valentino (1926) consequently became occasions for widespread grief, of a kind that had never existed before. Each was a universal loss, felt on an individual level.

Of course there had been famous people before films stars, be they theatrical performers, military leaders or royalty, whose lives were followed by those who never saw them, or only occasional images of them, and whose passing was the cause of extensive grief. And newspapers, magazines, posters and other media from the mid-19th century onwards distributed images of the glamorous and famous that could be widely shared. But cinema not only greatly widened the potential for appeal (across national boundaries as well) but created something on top of this: a feeling of closeness. Cinema’s performers openly appealed to you, that individual member of the audience. There might be eight hundred other people with you in the cinema shared the experience, but you along with they also felt it individually.

The memoirist C.H. Rolph identifies something of this in his book London Particulars, where he writes about seeing Chaplin in a London cinema in the 1910s:

The universal Chaplin impact was something I shall never really understand. For years it seemed to me that there are so many totally humourless people in the world that success on the Chaplin scale simply shouldn’t be possible, that it is a phenomenon calling for some transcendental explanation. Then I saw that this point of view merely rationalizes the feeling, in the breast of each Chaplinite, that Chaplin really belongs to him alone, that there is no one else who quite understands just how funny life can be.

The reach that David Bowie enjoyed was greater than even Chaplin enjoyed. Multi-channel television, the internet, social media, a proliferation of forms in which the sound and vision of the man can be produced, shared, consumed and reused creates a saturation effect en masse, but each individual experiences this differently. There are, or were, eight hundred, or 800 million, David Bowies out there.

The quality of the experience seems different to that of Chaplin’s time, however. Chaplin became a friend to millions, but he was remote for all that, an impossible figure whose real life was only really understood there on the big screen. David Bowie you could imagine meeting, and having a chat about anything (“so David, that line you wrote about Mickey Mouse having grown up a cow – what were you thinking?”). This is what television has done, of course, making familiar that which its predecessor medium made distant.

But if the quality of our knowledge of these people has changed with the media over the years, the fact remains that cinema ushered in a key aspect of modern life, which is that we know more people than we know. We know more of people, we invest more emotionally, because of the world that has opened up for us through what is beamed onto screens. We are, logically speaking, more sociable than our ancestors.

And so we mourn the passing of those we have never met, because we knew them anyway, and they were a part of ourselves.

And I still feel sad about Pete Duel.

A version of this post is included in my book Let Me Dream Again: Essays on the Moving Image (Sticking Place Books, 2025)

It wasn’t that Elvis’ acting that was so bad – it was the scripts, choice of director, and Tom Parker his manager that ruined what little career in the movies he had.

Well hello Olwen,

I was recalling my opinions aged 16, but equally giving Presley a good script, good director and freeing him of Tom Parker wouldn’t necessarily have made him a good actor. Though when was given a good director – Don Siegel, who directed Flaming Star – then he wasn’t too bad. But in general he was better off sticking to singing.

Curiously, when you think of it, David Bowie wasn’t that much good at singing or acting. But he had the songs. And the clothes.