Next up in this series of reviews of 2015 and those of its cultural treasures that fell my way is reading. I’m always astonished by those sections in ‘quality’ newspapers in which the great, the good, and journalists tell you the best of what they have read during the year. They all seem to have been able to plough through a mountain of newly-published books, in between their busy lives of media engagements, attending every film, play or exhibition you can think of, and writing a couple of books themselves. I do not know how it is done, though I feel not everyone may be telling the whole truth. Or maybe the great and the good and journalists just make better use of their time than we common folk.

As it is, I have read quite a few books this year, because I usually have three on the go at any one time, and I have managed by a huge effort of will to keep my media engagements to an absolute minimum. So here are some of the books I enjoyed in 2015 (one or two of which were actually published in 2015), together with some of the drinks I drank while doing so (follow the hashtag #thebookimreadingthedrinkimdrinking or visit its Flickr album if you want to find out more).

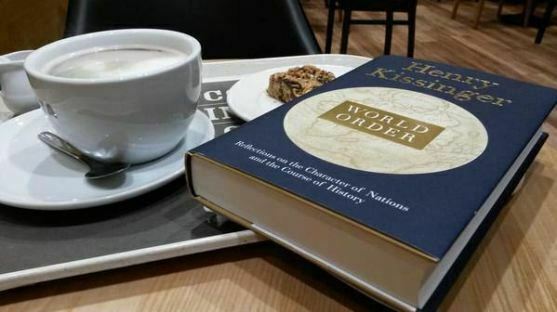

My book of the year was published last year, but felt fresh enough to be as much news as historical survey. Henry Kissinger’s World Order: Reflections on the Character of Nations and the Course of History is entirely equal to the lofty ambition of its title. I’m just about of the generation that remembers Kissinger as supposedly being the embodiment of all evil, the man of whom Tom Lehrer said that political satire died when he was awarded the Nobel Peace Prize. Now it looks like he was wiser than us all, wiser at least in appreciating the tectonics of global power. There can be no better book for helping you to grasp how the world may work, and how everything is rooted in history. It is also an absolute pleasure to read: a model of good style, with countless sharp observations and pithy summations of complex issues. How about this for a one-line explanation of how the First World War started: “World War I broke out because political leaders lost control over their own tactics”. What else is there to say? This is a book to cherish not simply for its explanation of history and politics, but for its exemplary display of fine English.

Trying to understand the world and the particular traumas it currently faces it something we’re all trying to do (unless hiding our heads in the sands feels like a better option), and I found two books to be helpful and well written. Paul M. Cobb’s The Race for Paradise is a clear-sighted history of the Crusades from the Islamic point of view while Gerard Russell’s Heirs to Forgotten Kingdoms, on the disappearing religious faiths of the Middle East, is a modern classic from someone with personal, probably unique knowledge of – amongst others – Mandaeans, Yazidis, Zoroastrians and Copts.

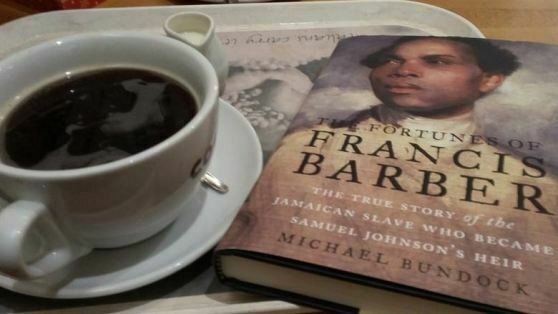

I like it when one book so engrosses you that its subject leads on to another book to read and then another, down avenues of enquiry which you hadn’t expected to find interesting or hadn’t previously given much thought to. As it happens, I’ve long been interested in the history of black Britons of the eighteenth century, but this year I found myself reading The Letters of Ignatius Sancho, the black British bourgeois who befriended Laurence Sterne and whose life was so ably recreated on the stage this year by Paterson Joseph, and then on to Michael Bundock’s The Fortunes of Francis Barber: The True Story of the Jamaican Slave Who Became Samuel Johnson’s Heir, published this year, which is the sort of history where discoveries lightly expressed but clearly won after deep research make for an exhilarating read. I also read Wenda Parkinson’s This Gilded African: Toussaint L’Ouverture, published in 1978 but still a very useful introduction to the tragic story of the man who lead the greatest of slave rebellions, a greater revolutionary than the Napoleon who eventually overcame him.

I read only three novels this year, and one of them was the re-reading of an old favourite, but that’s still three times my usual annual rate. As it was, Gordon Burns’s Born Yesterday, from 2008, is subtitled ‘The News as Novel’, and you could read it as a history of 2007 plucked from its news headlines. That is more or less what it is, a treatment of the news as fiction, interweaving the Glasgow car-bombings, the disappearance of Madeleine McCann and the transference of the country’s leadership from Tony Blair to Gordon Brown in an extraordinary brew that is quite unlike any other novel that I’ve read (there are no characters bar those real people shaped by the news or trying to stay in control of it). I don’t know whether it was good as such, but it conjures up many recent memories and makes you think about how the news frames the stories of our lives.

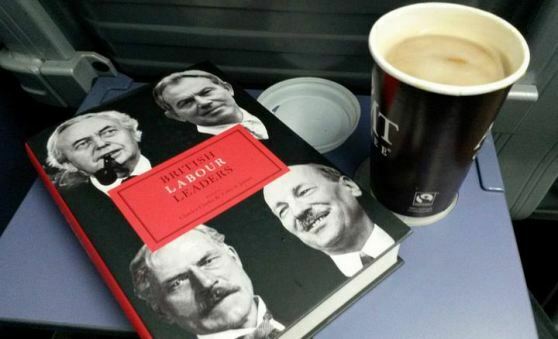

Talking of such things, I’m halfway through Chris Mullin’s three volumes of diaries about the self-deprecating Labour MP’s experiences between 1994 and 2010. this have been praised to the skies and deservedly so – you’ll find no better (nor more prescient) account of the dilemmas a leftwinger such as Mullins faces between idealism and pragmatism. Useful, rather than gripping as such, is Charles Clarke (yes, that one) and Toby S. Jones’s British Labour Leaders, a series of essays on the leaders of the Labour party and how they measure up against an analytical framework that the editors say will tell us what makes a good leader (they include league tables). There are separate volumes on Conservative and Liberal leaders (the latter may be a tough sell, I fear).

Normally my year’s reading features a number of books with a bookmark sadly left halfway through, as I gave up trying to struggle my way through them. This year I’ve managed finish most of what I started, but I did have admit defeat with Jonathan Sumption’s Cursed Kings. the fourth volume in his much-acclaimed history of the hundred Year Wars, it covers the period after 1400 up to the battle of Agincourt, and I bought it to acquaint myself better with the centenary celebrations, but after 200 pages we were still ten years away from the battle, and I grew weary. Magnificent research in a magisterial style, but it looks like the bookmark will be positioned in the same place for some while. Likewise for Laura J. Snyder’s Eye of the Beholder: Johannes Vermeer, Antoni van Leeuwenhoek, and the Reinvention of Seeing, which is dazzlingly well researched and I felt that little bit more clever just for possessing a copy. But the pages turned over ever more slowly and in the end I had to admit defeat (and to a realisation that I’m just not as clever as I’d hoped).

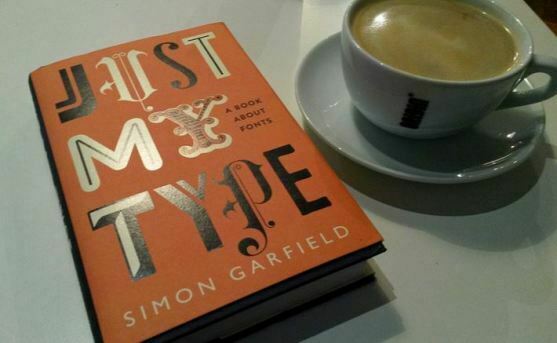

And there was more, including Theater of Cruelty, a collection of essays on art, film and war by Ian Buruma, one of my favourite authors; Richard Ingrams’ breezy The Life and Adventures of William Cobbett; Brian Cathcart’s entertaining The News from Waterloo: The Race to Tell Britain of Wellington’s Victory; Simon Garfield’s wide-ranging and beautifully-designed history of fonts, Just My Type (the sort of book you have buy just because it looks so good); Jon Ronson’s So You’ve Been Publicly Shamed – a book of the moment (it’s about people hounded by the modern-day mob that is Twitter), but to me it it didn’t quite make the points it could have made; and currently James Shapiro’s year in the life of Shakespeare, 1606: William Shakespeare and the Year of Lear. The title’s a bit of a cheat, since King Lear was written in 1605 and much of the book centres around the Gunpowder Plot of that year, but it’s a brilliant bringing together of history, character and literary studies. It makes you think all Shakespeare lessons in schools should be combined with the history curriculum – we can only understand Shakespeare for our times if we appreciate him in his.

Finally, one of my favourite books of the year is The Collected Poems & Drawings of Stevie Smith, edited by Will May. It’s such a pleasure to find the complete works presented so handsomely – a delight to the eyes, apart from anything else. It’s clear that Smith wrote too much that was off the cuff, so that a selected poems is better option for most, but it has rekindled for me the fondness I’ve felt for her poetry since the late 1970s, when I saw the delightful film Stevie (with Glenda Jackson and Mona Washbourne – now there’s a film in urgent need of a re-issue) and had to find out more.

I hope there’s enough there to encourage one or two to investigate some fine writing mixed with valuable ideas. And maybe I’ll make that little bit more of an effort to read more novels in 2016 – if the media will let me.

Next up, the year in film.