This is one of the most beautiful buildings I’ve ever seen, and I’m trying to work out why. It’s the stadium built for the Olympic Games of 1936, held in Berlin, a city that I visited for the first time a couple of weeks ago. The 1936 Games were of course Hitler’s Games, engineered as a means to promote the ideals of National Socialism. The design of the stadium and the site of which it was a part was integral to that propagandist and pernicious ambition, but just as with the Games, where sport triumphed over political show, so the stadium stands as symbol of all that is fine over blind prejudice.

The brochures and the excellent explanatory notes about the site conduct a careful balancing act between celebrating the sporting occasion while condemning some of the ideas behind it. The stadium has an interesting history. The site, at Grunewald on the outskirts of Berlin, first gained an association with sport in 1906, when the Berlin Horseracing Association commissioned Otto March to design a racecourse. This opened in 1909. Three years later work began on the construction of a stadium on the site, intended for the 1916 Olympic Games which were to be held in Berlin. The stadium opened in June 1913, and though the Games were cancelled because of the First World War, the stadium because a popular venue for sporting events, as well as political and military displays.

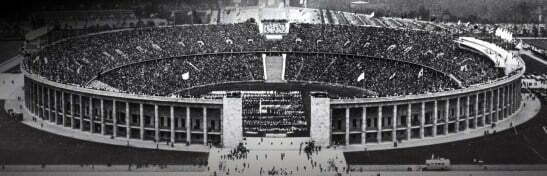

The site was further developed in the 1920s by Werner March (Otto’s son) as the Deutsches Sportsforum, though the financial crisis of the late 20s put paid to developing the site entirely. When Berlin was awarded the Olympic Games of 1936 the initial plan was to the existing stadium, but Hitler demanded a complete rebuild, which was overseen by Werner March. A much larger stadium seating 100,000 would now be built on the site of the existing one (digging down into the ground to achieve greater space than one would expect viewing it from the outside), and the overall area to become the complete sporting complex, named the Reichssportfeld. Completed in 1936, the Reichssportfeld and the Olympiastadion hosted the spectacular Berlin Games in that year, an event which in its ambition, aesthetics, symbolism (the first Games to have the Olympic torch relay) and sports professionalism established the success and the still present meaning of the Olympic Games. With the stadium as the centrepiece, there was also the Olympischer Platz road leading up to the two-towered Olympic gate and the stadium beyond, the large field at the end end of the stadium overlooked by the Bell Tower, the swimming pool and an open-air amphitheatre.

The stadium was largely unaffected by the bombing of the Second World War. The Bell Tower was demolished in 1947 (to be rebuilt in the 1960s) but the substantial structures remained and the stadium was regularly used for sporting events and festivals. It was used for the 1974 World Cup and was significantly refurbished – including the addition of a roof – in time for the 2006 World Cup. Today it hosts football matches and concerts. It is an active and much-used area. But if you visit it on a cold, sunny day in February when there are no events scheduled, as I did, then you get the entire stadium more or less to yourself (there is a visitor centre, and tours are available, but otherwise you can go around the entire site and most of the stadium for yourself, unaccompanied).

I found the experience thrilling. In a large part this is because I’ve long been an Olympic Games history enthusiast. The idealism behind the founding of the modern Games may been been naive, and the use of the Games through history may have been frequently contentious, but the beauty of the central idea – the unification of people and the celebration of excellence through sport – trumps the failings of reality every time. You sit in the stadium and think, that’s where Jesse Owens ran, that’s where he and German long jumper Luz Long befriended one another (to the delight of the crowd and disgust of the Nazis), that’s where Jack Lovelock won the 1,500 metres, that’s where Glenn Morris won the decathlon, that’s where Sohn Kee-Chung (a Korean forced to run as Japanese under the name Son Kitei) won the marathon, that’s where Leni Reifenstahl filmed probably the greatest of all sports documentaries.

Riefenstahl’s Olympia doesn’t get shown much these days – not because of the hold its late filmmaker had over its distribution, but because the International Olympic Committee now owns the film rights, and it seems to be a bit self-conscious about the fact. If you see the film, you understand why Olympism triumphed over fascism. The opening reel of Olympia is portentous stuff, with statuesque athletes in half-lit, cod-Grecian poses, that chime in well with the Nazi aesthetic. But then the Games take over. The politics are reduced to nothing, as all we see is human physical excellence, ingeniously filmed to exhilarating effect, the literal record artfully combined with the abstract (notably the diving pool sequence). The drama of actuality has never been so ably orchestrated as it is in Riefenstahl’s film.

So you sit in the stadium, contemplating the the raw materials with which she made her film, and how art – if it is true art – always transcends the political. But it wasn’t just how the Nazi showcase was trumped by sport. It was something about stadia themselves. Buildings are designed for a human need. Their aesthetic function is subservient to their social purpose. If they are beautiful it is because they serve people beautifully. This the Olympic Stadium demonstrates to perfection. Functionally, it is a model stadium because every seat provides an excellent view. Visually it does so through the harmonious use of shape and line. I was just so moved by how we can build spaces for human celebration, and how the stadium (from the Colosseum to the Nou Camp) channels drama through the effective marshalling of the crowd. Here we cheer amongst our peers, Here is where we win.

Another part of the thrill of the visit to the Olympiastadion is that it was empty, or virtually so. There was a handful of visitors, and a film crew that milled around the cauldron at the Marathon Gate end of the stadium for a while. Essentially I had the stadium to myself, on a clear day with perfect sunshine. The sounds of the crowds were only virtual echoes. To be in such as place which has had such political portentousness placed upon it, as well as such sporting endeavour, and to see all that reduced to silence, has a powerful effect on the emotions. That which is evil will pass, and all that will survive of it will be the good. I found the Olympiastadion to be a hopeful place.