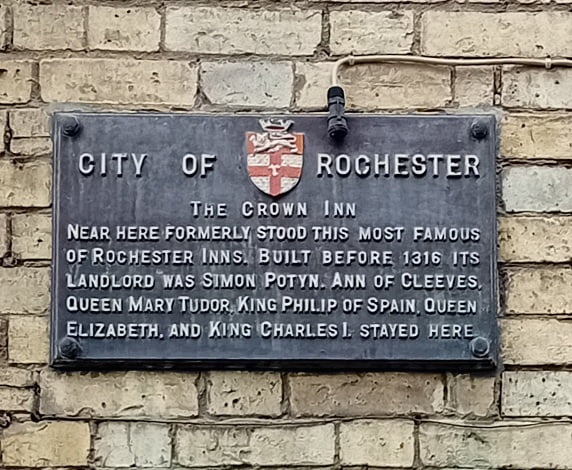

At the top of Rochester High Street, where the bridge crosses over the Medway, there is a pub with a long history: the Crown. The present building, which dates from the late eighteenth century, is adjacent to where the original building (built early fourteenth century, now lost) once stood, most notably providing accommodation for passing dignitaries who had come across from the continent. They would stay overnight in Rochester before arriving in London, looking at their best, the following day. A plaque, hidden away down an alley behind the Crown, documents some of the most notable of those who spent the night there.

There is surely the subject here for some fantastical drama in which Anne of Cleves, Mary Tudor, King Philip of Spain, Queen Elizabeth I and Charles I all find themselves at the inn on the same night and contemplate the strangeness of history and fate. Though their periods on this earth stretched for over a century, they would find themselves free from chronology, the Crown serving as time-free space and metaphor. They exist because they are remembered, and being memories they may wonder if they ever truly existed at all. Perhaps it would be a topic for Caryl Churchill (thinking of the opening scene of Top Girls), or maybe Peter Morgan…

Wind forward four hundred years or more, and a new Crown has come to town. In an apposite location, and on the birthday of the late Queen Elizabeth II, the Netflix series The Crown set up shop in the street outside my place for the filming of events around the marriage of Prince Charles and Camilla Parker-Bowles in 2005. Some location scout had decided that Rochester High Street could be convincingly re-imagined as Windsor (the 2005 wedding took place at Windsor Guildhall), while the outside of Rochester Cathedral could serve the arrival of Tony and Cherie Blair. I did not see the latter, but from my front window I had a bird’s eye view of the arrival by car of Charles and Camilla, played by Dominic West and Olivia Williams. The key scene in which they got out of the car, took place outside Rochester’s own Guildhall, a stone’s throw from the Crown inn. Reality, fantasy and history combined in uncanny fashion.

Theme and location may have come powerfully together, but not even so prodigious a weaver of myths as Netflix can control the weather. And so it rained.

It was grey and dismal over Rochester when the crew starting setting up early in the morning of 21 April. Spotlights from a giant crane shone onto the upper part of the Guildhall, but this semblance of regular light could not prevent the signs of dampness on the sets and extras below. Flunkies with cloths wiped down surfaces, while the extras – including policemen and women – wore see-through macs, to be removed once any filming began. They gathered behind crash barriers beneath my window, they waving to me, me waving to them. They were a beguiling mish-mash of British ordinariness, equipped with Union Jack hats, celebratory bags with images of West and Williams, and cameras of 2005 vintage provided by the meticulous crew.

The day progressed, with background shots organised by a man in a blue woolly hat who seemed to be everywhere, encouraging the waiting extras to show appropriate enthusiasm, despite the conditions (“remember everybody, you are happy”). Then magically, because the power of Netflix may be still greater than any could have imagined, as things built up to the excitement of the couple being driven repeatedly up the street in a black Rolls Royce and then filmed repeatedly getting out of said vehicle, the sun began to shine. The crowd responded, cheering with increasing fervour. Who were they cheering? Was it Charles and Camilla, or Dominic and Olivia, or themselves for taking part in this game where past felt close enough to the present to be the present? What, at the end of the day, is the difference between the actuality and its representation, so far as our hearts are concerned?

Over it all, director Stephen Daldry went about with quiet authority, the true ruler of this fantasy land. Beneath him were tier upon tier of subjects, from the star actors, to the key crew, to the extras, to the humble carriers of coffee cups, those on the bottom-rung of the TV production ladder and this little world to which we were so privileged to have been invited.

The Crown, should you not know, is a television series on the life of Queen Elizabeth II, produced by Left Bank Television and Sony Pictures Television for Netflix. Its genesis was in a 2013 play, The Audience, by Peter Morgan. In this the Queen, originally played by Helen Mirren, has audiences with each of the prime ministers of her reign, through which we learn about the changing temper of the times. Morgan developed The Crown far beyond that modest premise. It has run to five series so far, with one more to come that is currently in production. and has become a global talking point. The reason for this is chiefly prurience – the series offers what appears to be a particularly privileged portrait of the British royal family behind the scenes, with the added piquancy of taking place while its subject was alive. It has felt more now than history. It is the latest contribution to the undermining of mystique that has taken place ever since the reluctant royals first thought that they ought to appear before motion picture cameras, because the humble folk needed pleasing.

When exactly that point occurred is contentious, but I would put it at 1917 – not coincidentally the year in which the House of Saxe-Coburg and Gotha thought it would be wise, given that the country was at war with Germany, to change its name to Windsor. It was then that King George V and Queen Mary started to be seen more in the newsreels that featured in every cinema, notably in the wartime propaganda newsreel, the War Office Official Topical Budget, subsequently known as Pictorial News (Official), which was established in 1917. Royalty had appeared on film before then, but always at a distance, and only on rare occasions. Now they were performers, seen closer because camera operators were granted better positions for filming, and increasingly defined by how they appeared on the democratic screen. The audience’s desire to get ever closer – from the 1937 coronation (filmed, but at a distance), to the 1953 coronation (when the TV cameras humanised their royal subject despite the desire to show awe), to the informality of the 1969 television documentary Royal Family (how thrilled we were at the time to see Queen buying ice creams for her offspring – just like us) – has led to the frankness of drama. When the camera zooms can go no further, we demand to see their hearts.

The Crown has been praised for its production values but heavily criticised for deviations from factual history and its treatment of recent events still raw in the memory (Diana). The fact that the series is ending with the wedding of Charles and Camilla – an event which took place in 2005, when the Queen herself lived until 2022 – suggests that all concerned feel that it is time to draw things to a close. When the story becomes how you are untrue to the story, you break the spell. You find that their hearts are closed after all.

And so it ends, symbolically at least, in a damp street in Rochester, while the extras, the public and the ghosts look on. Ghosts, because I like to think of Anne, Mary, Philip, Elizabeth and Charles gathered outside the Crown inn, looking at this curious spectacle and wondering whether it shows the end of the drama in which they once played their part, or whether the drama must forever continue. They have been gathering together in the Crown for centuries, long after the original building was pulled down. They have seen how time has turned them from real figures to ever-changing fantasies. They have haunted into the age of screen performers, and, though at first appalled by such travesties, they have come to understand that they are those who choose to play them. This has become their existence.

They pick their favoured imitators: poor Anne rather likes the smart intelligence Elsa Lanchester reveals in The Private Life of Henry VIII; Mary goes for Romola Garai in last year’s Becoming Elizabeth, pleased by the sense of how contemporary she can be; Philip favours Ben Willbond in Horrible Histories’ Bill, because not enough people appreciate he could be a funny guy; Charles has no choice but to go for Alec Guinness in Cromwell; Elizabeth admires and is flattered by Cate Blanchett, but knows it was Glenda Jackson who could read her heart.

They don their personas and walk unseen among the viewers of the spectacle. They join in the dance that ended the shoot, a jazz band playing ‘Congratulations’ for the cavorting royals, while the people clap along. And they recognise Dominic and Olivia as one of them.