A few years ago I thought it would be a useful thing for the British Library (my employer) to have a shareable list of its newspapers. I had been speaking to an American archive with whom I wanted to share the records we had, and it seemed a reasonable thing to do. There had been a printed catalogue in the past, but it was out of date, and while up-to-date records of the newspaper holdings were on the Library’s electronic catalogue, they could only be seen on the catalogue alongside everything else that the Library holds. So I put in a request to the metadata team for a spreadsheet of all the newspaper titles – and that’s where the adventure began.

What I thought might be a matter of a few weeks ended up taking three or four years. The spreadsheet of the 35,000 newspaper titles held by the Library was duly produced by the metadata team, but it was riddled with inconsistencies. Over the period of nearly two hundred years that the British Museum and then the British Library (parts of which used to be located in the Museum) had taken in newspapers, there had been quite a few changes in cataloguing style and priorities. There were gaps in location codes, start or end dates, identification number of one sort or another, publisher details and information on whether a newspaper was a daily, weekly or whatever. There was no absolute consistency.

The more one knows of newspaper history, the more obvious this has to be. Newspapers often change title (every time a newspaper does so the Library creates a new catalogue record – logical in cataloguing terms, a little exasperating when producing a list and finding the newspaper in which you are interested appears in half a dozen places). They can change publisher, they can change location of publication, they can change from being a daily to a weekly, or might have been published two or three times a week. The very nature of the medium contradicted the idea of creating the perfect list.

We worked off-and-on at the list, thinking after each stage of data cleaning that we had ironed out the major gaps or anomalies, only to find that more would pop up. I thought of giving up the idea, only for a wiser head at the Library to say that we should produce something imperfect rather than produce nothing at all. Then I was lucky to find a data specialist working with me for a time, and I handed the task to him, having decreed that we should simplify the task by keeping to British and Irish titles only (two thirds of the collection; one geographical term field to be filled in for every title (there are six possible geographical fields used for newspapers at the Library); and each title to have a start and end date. This was manageable, and would result in a list that, in spreadsheet form, could be shared and then sorted in a form that users would find useful. It took a couple of months.

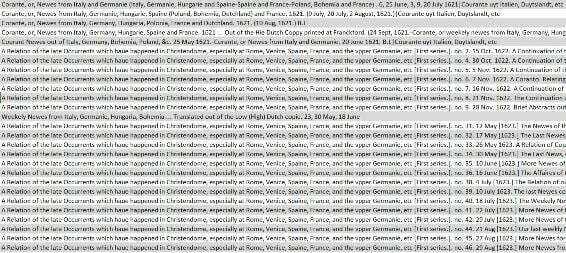

The list has now been published on the British Library’s Research Repository, where anyone can download it. 24,000 titles, four hundred years of British newspaper publication (1621 saw the first newspaper printed in Britain). An article written by myself and Yann Ryan, the data-wise colleague who completed the work, has been published online by the Journal of Open Humanities Data. We’re now working on a list of all newspaper titles held by the Library i.e. not just British and Irish but world newspaper holdings, some 35,000 titles in all.

All of this has made me think about the nature of lists. I am inveterate list-maker – it goes with the profession – but all of us are list-makers to some degree. Some list all of the nation’s collection of newspapers; some work out the week’s shopping. We need the things that are useful to us to be in clear order, or else all is chaos. Lists give us the reassurance that we are in control, that we understand things.

The pre-eminent book on lists is Umberto Eco’s The Infinity of Lists (2009). It is a collection of lists from the literary to the bibliographical to the religious to the mundane, gorgeously illustrated (it was commissioned for a Louvre exhibition). Each section (The Visual List, Lists of Places, Lists of Mirabilia, Chaotic Enumeration, Mass Media Lists etc) comes with Eco’s speculations on the nature of lists. The arguments are rich and intoxicating, but might be boiled down to what is signalled by the title: the relationship between lists and the infinite.

The pre-eminent book on lists is Umberto Eco’s The Infinity of Lists (2009). It is a collection of lists from the literary to the bibliographical to the religious to the mundane, gorgeously illustrated (it was commissioned for a Louvre exhibition). Each section (The Visual List, Lists of Places, Lists of Mirabilia, Chaotic Enumeration, Mass Media Lists etc) comes with Eco’s speculations on the nature of lists. The arguments are rich and intoxicating, but might be boiled down to what is signalled by the title: the relationship between lists and the infinite.

Some lists attempt, albeit theoretically, to list the infinite, as is implied by Borges’ Library of Babel, or a philosophical exercise such as Raymond Queneau’s Cent mille milliards de poèmes (A Hundred Thousand Billion Poems), a book of ten sonnets whose pages are broken into horizontal bands whose permutations result in a virtually infinite number of potential poems.

Yet all lists contain within them the potentiality of the infinite. As Eco argues, the list, or catalogue “suggests infinity almost physically, because in fact it does not end, nor does it conclude in form”. The list, or catalogue, is a response to the fear, or the attraction, of the infinite. These are the products that I could have bought on my shopping trip, but I could have bought anything, given unlimited resources. These are all the books in my collection, but there are all the others books that I might have acquired, or ought to have, or might want to acquire in the future. I can give you a list of my ten favourite films, but that is an admission that I should see every film there ever was (or will be), that in doing so I could order them all in terms of merit, but even to think of such a task is unimaginable. So, to save myself I pick ten, and stop there, turning away from the abyss.

However, there is a form of list that seems to be missing from Eco’s catalogue of lists. He addresses the digital world, saying of the World Wide Web that it is “the Mother of all Lists, infinite by definition because it is in constant evolution”, but it is given just a paragraph, almost dismissed because it does not let us distinguish between what is from the real world and what is not – “there is no longer any distinction between truth and error”.

But what of the spreadsheet?

Spreadsheets are the infinite made viable. A sufficiently complex spreadsheet, with its many columns and rows, suggests potentially limitless permutations. The title-level list of British, Irish, British Overseas Territories and Crown Dependencies newspapers held by the British Library lets me list the newspapers chronologically, or by different kinds of location, or variants within these (so I can list all newspapers from Yorkshire 1800-1900, for example). But I can go further – particularly if I can apply some software analysis tools, so that I could list the newspaper titles by length, or by the dates at which they ceased publication, or by recurrence of particular words, and again with variants based on date or location or identification number, or whether the newspaper has been digitised or not, or any number – literally – of the orderings that a list of 24,000 object classified under twenty-four columns.

Here is the pure library – infinite not in extent but in possibility. One could imagine a team of librarians endlessly rearranging the physical volumes of newspapers on which the list is based into the order conjured up by the dreams of researchers. I need every newspaper published in London arranged in order of the duration of run, with shortest-lived newspapers first, with those of equal duration further ordered alphabetically by title. Do that, and my world will make sense.

Of course, indexing systems have long offered such an infinity of permutations, by separating subject from object (one object in your collection may require multiple subject indicators, and each of those subject indicators may relate to any number of objects). However, the spreadsheet does not just show you what can be found, but what you did not imagine could be found. It is a temptation to play God with a reality.

Of course, because I know how many columns and rows there are in the newspaper lists, it should be possible to come up with a finite figure of permutations of that data, much as Queneau’s ten sonnets will only result in one hundred thousand billion poems. But it is the intimation of the infinite that is important. Every finite list contains within it the potential of the infinite, and the spreadsheet makes this manifest. Maybe Eco has written somewhere else about spreadsheets (if so, I don’t know of it), but surely he would have been thrilled by the potential of the large datasets we produce these days that can be mined for all kinds of scholarly enquiry (the industrial, political and economic use of large datasets we can set aside for another argument on another day). It has brought the theoretical into the realisable.

But there is another side to this. The spreadsheet reveals the insecurity of lists. The list is no longer what it asserts to be, as with most of the linear lists that Eco lovingly reproduces (from Homer, Aristotle, Walt Whitman, Italo Calvino, James Joyce, the Bible, and high priest of lists François Rabelais). It tells us of all the things that the list could otherwise be, taunting us to think of the next permutation while knowing that a permutation lies ahead that will be beyond our imagining.

Those whose mine such datasets are called data scientists, but science does not seem to be the right word. They are arch romantics, faced with infinite choice, but knowing that to choose is to fail. But still they choose again.

Links:

- The paper Converting the British Library’s Catalogue of British and Irish Newspapers into a Public Domain Dataset: Processes and Applications is published by the Journal of Open Humanities Data, which is very keen on correct citation, so here is the correct citation (and no I don’t know why giving an initial instead of your actual name is supposed to be better) – Ryan, Y. and McKernan, L., 2021. Converting the British Library’s Catalogue of British and Irish Newspapers into a Public Domain Dataset: Processes and Applications. Journal of Open Humanities Data, 7, p.1. DOI: http://doi.org/10.5334/johd.23

- A title-level list of British, Irish, British Overseas Territories and Crown Dependencies newspapers held by the British Library is available to download and sort to your heart’s content from the British Library’s Research Repository

“the spreadsheet does not just show you what can be found, but what you did not imagine could be found.”

What a lovely turn of phrase! — and a pretty good capsule insight on the power of spreadsheets.

Part of my job is massaging / manipulating / cleaning up / reorganizing large spreadsheets, and above all, extracting the most relevant data for a given purpose in the most practical & efficient way. My background in symbolic logic and “data grammar” sometimes helps me find information or relationships that even the data owners didn’t know was there or was accessible.

Congratulations on getting your newspaper list organized. I can imagine how satisfying that was.

P.S. I hit your site randomly by searching for good explication of the meaning of “The Third Man” movie title. Really enjoyed that essay!

Thank you. We keep on coming up with fresh ways to find out more. I hope the Third Man post answered your question.