I find this photograph fascinating. Not for the man with the motion picture camera that looks like some form of primitive machine gun, not for the late Victorian gentlemen oozing privilege to the tip of their top hats, but the man on the far left. He is half in, half out of the picture, looking up at the man with the camera – maybe out of curiosity, maybe awaiting instruction. He is one of those background figures in old photographs who were not the focus, of whom the picture tells us nothing, yet there was a life, frozen for an instant before vanishing into obscurity. Where did he come from? What was he thinking at that very instant? Where did he go?

We know his name, however, or we think that we do. He is Henry William Short, known as Harry, or so someone who knew him once said of the photograph, since when Harry Short is who he has become. There are two other still photographs which show Short, in private hands, which do not help in the conformation of the photograph above. The uncertainty is part of the appeal. What you do not know about someone so often is that much more interesting than what you do know.

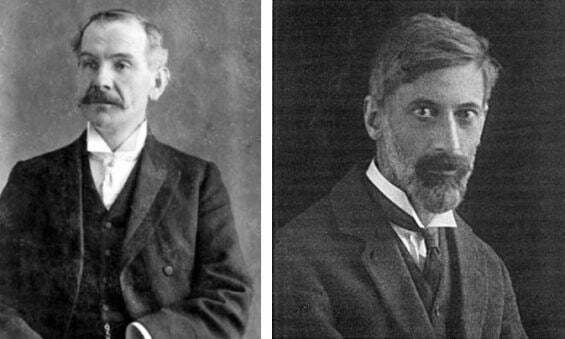

The picture shows inventor-photographer Birt Acres filming the Derby horserace at Epsom on 29 May 1895. The stand on which he is positioned was close to the finishing line. There are numerous ways of viewing the starting point of British film history, but the usual one is the coming together of engineer Robert Paul and photographer Acres in early 1895. Incompatible from the start, the two men between February and May of that year produced the first films to be made in Britain, among them that of the 1895 Derby, before going their separate ways, each pursuing their film ambitions. Harry Short was the man who brought them together.

Short’s great gift was bringing people together. On two occasions he made alliances which kickstarted film in this country. However, he was also one of the first British filmmakers, the first British travel filmmaker, he was probably witness to the first exhibition of projected film in this country, and he invented one of the more ingenious motion picture devices of his time. All this in two years, and then he disappears from film history. Let’s recover what we can, and see if it turns a figure frozen at the edge of someone else’s picture into a life we can understand.

Henry William Short was both in Lambeth, London in 1864. His father was Thomas Watling Short (1833-1906), who with William James Mason, founded a renowned firm of instrument makers, Short and Mason, also in 1864. They became widely-respected as specialist producers of barometers, anemometers and compasses, continuing in one form another until 1969, when the company was absorbed by American giant Taylor Instrument Companies. Harry Short was apprenticed to his father’s firm, proving himself to be a capable engineer, if perhaps with something of the maverick about him. There is nothing in the records to suggest that he was trained or even considered as suitable for carrying on the family business, but there are indications of an independent spirit, and not always a wise one.

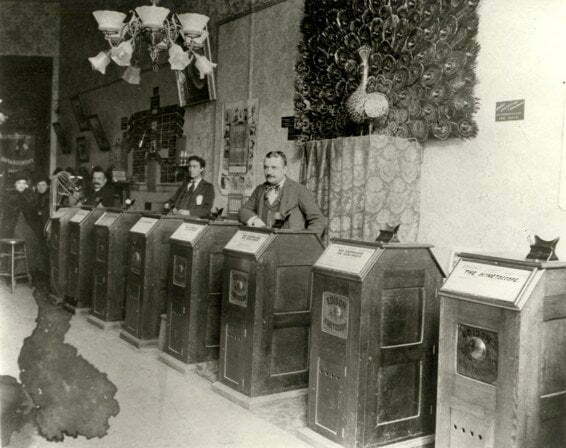

Short enters film history late in 1894. Motion picture film arrived in the UK via the Edison Kinetoscope, a peepshow device showing a loop of film, requiring the viewer to lean over and look down onto the tiny image within. One short film could be seen per device, so for exhibition purposes there would a row of such devices in so-called ‘parlours’, similar to and often alongside the earlier Edison audio-playing device, the Phonograph. Kinetoscopes were expensive and use of the films (made by Edison) strictly licensed through concessionaries.

But there were several who saw this new money-making device who wanted to get involved without involving Edison. One such group comprised a number Greek businessmen. Early film histories identify two of them, Georgiades and Tragidis, but recent research has shown that there were four or five Greek associates, who between them first legitimately presented Kinetoscopes in New York in the summer of 1894, then illegitimately presented Kinetoscopes in Paris (July) and London. We don’t know the date of their London debut: it could possibly have preceded the Kinetoscope’s official British debut in a rented shop space at 70 Oxford Street, London – on 17 October 1894, managed by Edison concessionaries the Continental Commerce Company. Two of the Greek team, Demetrius Georgiades and George Tragidis, looking for someone who might be able to build Kinetoscopes for them, turned for advice to a fellow London-based Greek, cigarette distributor John Melachrino. Melachrino had a regular customer, one Henry Short, who might be able to help them. Short introduced them to Paul.

Before taking this well-worn narrative any further, it’s worth taking note of John Melachrino. He was no ordinary tobacconist. The Melachrino family hailed from Constantinople and were part of a wave of Greek entrepreneurs who established tobacco businesses in Egypt, capitalising on growing global enthusiasm for cigarettes. One of the family, Miltiades Melachrino, went to the United States and grew rich marketing what became an iconic name, Melachrino Egyptian Cigarettes. John Melachrino settled in London in the 1880s, distributing the same brand. His son, George Melachrino, would go on to become a famous band leader, composer of film music (e.g. No Orchids for Miss Blandish) and purveyor of lush orchestral music beloved of 1950s radio audiences. He is commemorated on the Hollywood Walk of Fame. Two years after this encounter, Short would go to Egypt on a filming assignment for Paul, and one of the films he made there (now lost) was called Cigarette Maker. It’s hard not to think that Short had the Melachrinos in mind when making the film.

Short certainly knew Paul. Short and Mason’s offices were at 40 Hatton Garden, London; Paul’s at 44. In a 1936 lecture Paul said that he was introduced to the two Greeks by “my friend, H.W. Short”, though how deep or how far back the friendship was we do not know. Short was closer to Birt Acres, a photographer living in Barnet, not far from Short’s home in East Finchley (though Paul lived nearer, in Muswell Hill). Both were members of the Lyonsdown Amateur Photographic Association, and Short worked with Acres at photographic materials company Elliott and Son. At any rate, Paul needed someone to produce the films that would run on the rogue Kinetoscopes he was building, since having provided Georgiades and Tragidis with their request, he saw that there was a market there but that the films to run on the devices were jealously guarded by Edison’s people.

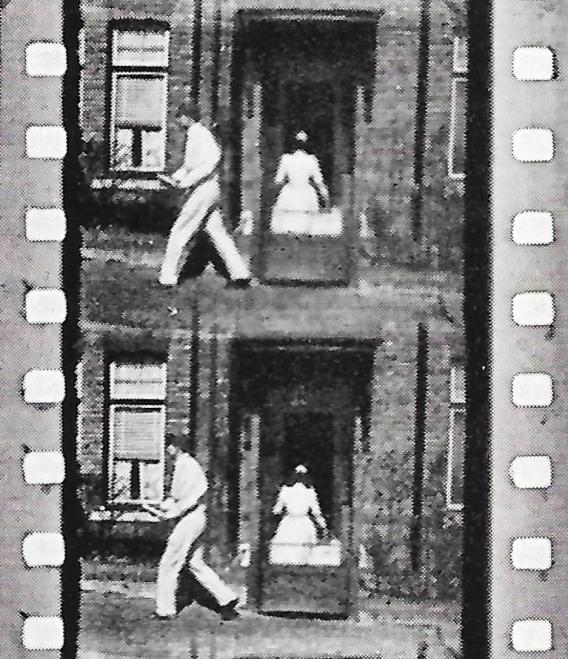

Acres and Paul developed a camera early in 1895. Just who contributed what to its construction became the subject of bitter dispute between the two men and is argued to this day by their champions. Short was in the middle of this, and not idle. The first test film shot by Acres, years later given the title Incident at Clovelly Cottage (Acres’s Barnet home). It featured Acres’s wife Annie and baby Winifred in a pram, with Short walking past the house dressed in cricket whites, ghost-like in the imprecision of the image in the few frames that survive of the first British film. It’s unclear whether it has a narrative at all, but it differed from Edison’s Kinetoscope studio-based films in being shot on location, in a humdrum London street. Acres, Paul and Short had made the first realist film.

The cricket whites, so the story goes, were so that Short would show up more clearly on the screen, but what if Short was simply a keen cricketer? Perhaps in the records of a Barnet or East Finchley cricket club there are scoresheets noting one H.W. Short, perhaps strong neither as batsman or bowler, but always energetic in the field.

Still more ghostly is the Acres’s maid, the fourth performer in this ‘first’ film. All we see of her is from behind, as she disappears into the dark house. A truly marginal life.

Acres and Paul acrimoniously parted company in May 1895, having made a handful of films for the burgeoning Kinetoscope trade, both now intent on building up a businesses separately through the obvious next step, projection on a screen (which would attracted more paying customers). Probably the last film made by the partnership was of the Derby horserace of 1895. Harry Short now flitted between one and the other, still friends to both, the Lepidus to the Antony and Octavian of this suburban triumvirate.

Short accompanied Acres on a filming trip in Germany the following month. Acres would later refer to him as being his ‘paid assistant’, which has a patronising, defensive air about it. The aim of the trip was to impress a German chocolate company, Stollwerck, which was interested in mechanical amusement devices and wanted to know about the new motion picture technology. Acres and Short filmed several scenes around Kiel (one survives, Opening of the Kiel Canal), but Stollwerck decided that another firm’s camera/projector was better, and did a wiser deal with the Lumière Cinématographe instead. The motion picture business was hotting up, and Acres was already falling behind.

Short moved on, looking to find a place for himself in this new industry. In February 1896, one month after Acres gave the first exhibition of projected film in Britain, on 10 January, to the Lyonsdown Amateur Photographic Association (it’s almost certain that Short, as a fellow member, was in the audience), Short patented an intermittent mechanism (the essential stop-start means by which motion could be capture on a strip of film and reproduced in projection). However, he seems to have done nothing further with this. He does seem to have gone to New York this same month (there is a Henry William Short on a Southampton-New York passenger list for 22 February 1896), on a two-week business trip on Birt Acres’s behalf. Acres released films of Niagara Falls and New York, presumably shot by Short, later in the year.

But then Short switched from Acres to Paul, signed up by the latter to take a series of films for him in Spain and Portugal over August and September 1896. Why Spain and Portugal? It’s likely that Paul was seeing the need to match up to the competition from the Lumières, who had a network of operators filming in a number of countries. But maybe Short had a personal motive, since immediately before setting out for Seville, Short got married. Harry Short’s marriage to Martha Scott on 2 August 1896 was the turning point in his career, in film at least. Up to that point, all had been full of excitement and promise. Now everything went into reverse.

The assumption is that the filming trip was a honeymoon trip as well. It is not impossible that Short actually left Martha behind, which might go towards explaining what was to happen to the marriage, but we do not know. We do know that he spent some six weeks filming what was promoted as A Tour in Spain and Portugal. Two of the fourteen films Short took survive, including a fragment of one that became a great success for Paul, A Sea Cave Near Lisbon, a scene of breaking waves seen from within a cave. Its artistic framing combined with its powerful sense of motion greatly appealed to audiences still absorbing the raw details of this new medium. However, though we may have too few films to go on, it does not seem that Harry Short was an exceptional filmmaker. He had an eye for composition and the movement of people, but lacked that spark that we see in, say, almost any film made by the Lumière operators at the same time. Short’s gifts lay in mechanics – and bringing people together.

In March 1897 Paul sent Short on another filming expedition, to Egypt. That same month his wife left him, after just seven months of marriage. The divorce records tell us that she refused to return to him (it is not said why), and that she went to to commit adultery over the next two years with a Mr McDonald. The end result was a child, born Reginald Joseph Short, on 29 April 1900. The father was unknown; Harry Short’s name is given on the birth certificate. It seems he had no subsequent connection with the boy.

We can only guess at what went on. Martha Short may have taken the opportunity provided by the Egypt trip to leave her husband. Maybe he agreed to the filming assignment to get away. The fact that Short retreats from the public record after this personal disaster has to be significant. Reading between the lines, there seems to have been strong family disapproval, along the lines of we told you so. The divorce went through in 1910, by which time Harry Short and film had long since parted. To fill in the gaps left by a slender history one could speculate on the relationship between the personal and the professional, two filming expeditions driven by the need to be together or to be apart: first sublimated passion, then disgust. Film tells us so little. It tells us only what the camera saw.

Whatever the reasons, he took thirteen short films in Egypt, all travel scenes, of which two survive: Women Fetching Water from Nile and Fisherman and Boat at Port Said. As noted, one of the films, Cigarette Maker, suggest a link with John Melachrino, but there is no evidence of the series having been commissioned by Melachrino or used as advertising in any form.

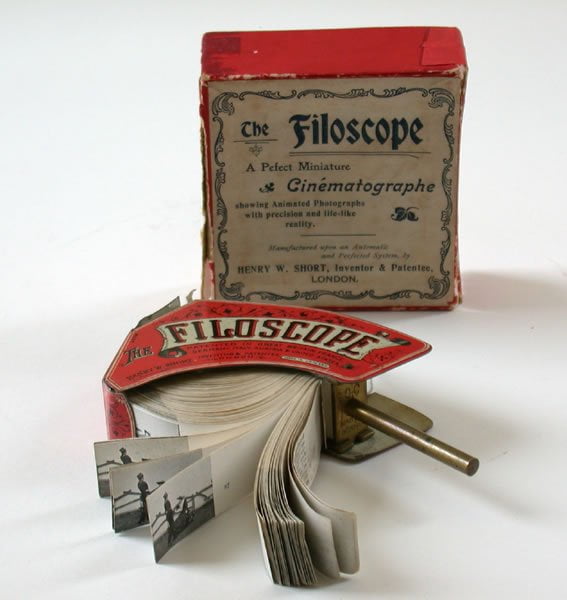

To progress in the burgeoning film business, Short had to stop being assistant to others and make his own mark. In 1897 he came up with the Filoscope (patented 1898). Short’s invention was a hand-held flip-book, in which the successive images of a film were printed on cards held within a curved metal case, with the illusion of motion triggered by pressing on a brass lever. At this time in film history there was as much effort to introduce films to the domestic market, through narrow-gauge home movie devices, as well as flick-books on various shapes and sizes. The Filoscope was compact, reliable and easy to use. Simple as it may now appear, it (and other flick-book systems like it) played an important role in introducing the general public to the motion picture. In some sense it was superior to the projected film in encapsulating the magic of the motion picture medium.

Moving pictures are an endlessly rich topic, but one could argue that they boil down to just two primary purposes. One is to display movement; the other is to tell a story. The latter is that out of which vast industries have been built that entertain us, instruct us and dominate our thoughts. The former is that which animated the film pioneers and intoxicated the first film audiences, movement itself. It is what engenders passionate advocacy among early film enthusiasts over the minutiae of competing mechanical technologies and causes fascination for fleeting moving images of undistinguished topics. It is the ever-repeating wonder that the thing moves, that that which appeared still could jerk into life. It’s that teasing revelation that we might immortalise ourselves. These two purposes have become almost completely separated in our consciousness, but just occasionally there is a salutary reminder – when that online video tells you that it is buffering and you see nothing but a whirling circle as the technology sorts itself out. Oh look, it’s come back to life again.

Short’s Filoscope epitomises this revelatory moment. The photo-realistic figure is still; at the touch of a finger, the figure moves. It stops and starts at our command. It makes us god-like.

The Filoscope used films produced by others, including Robert Paul. It was backed by a company, the Anglo-French Filoscope Syndicate, which Short formed in 1897. It must have enjoyed some success, but not enough to establish Short in the film business. He was in retreat. There was one more film-related patent, ‘Improvements in Kinetoscopic Apparatus’ in 1898, but nothing more. The added trauma of Short being attacked by a jemmy-wielding burglar in December of that year, leaving him with head wounds, must have contributed to a sense of things falling apart. There is something about Harry Short that suggests someone not quite tough or wise enough to make the best of himself. Various sources refer to him as ‘young’ Harry Short, yet he was the same age as Acres and Paul. He was obliging, he was used. He needed others, but suddenly they no longer needed him.

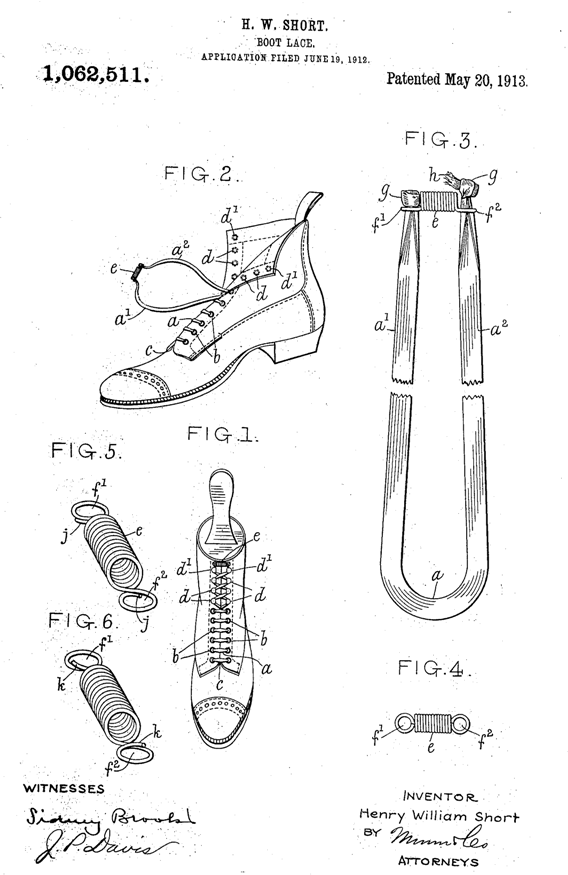

He carried on working as an electrician and engineer. Patents followed, some linked with Short and Mason, showing that he retained some connection with the family firm. There was an application for ‘Improvement in magnetic compass needles’ in 1904, and approved patents for ‘An improved megaphone’ in 1909, ‘Improvements in and in the Manufacture of Whistles’ the same year, ‘Improvement in boot laces’ in 1913. He tinkered away at many things. His business moved to Seven Sisters Road, working more in gas than electricity by this time. He died in 1919, aged fifty-five, intestate, seemingly alone. No film journal or newspaper noted his passing. He is buried in an unmarked grave in a churchyard at Mutton Lane, Potters Bar.

Harry Short is one of film history’s footnotes. We need these footnote people, who intervened for a moment in the greater thread of things. There is never enough in them to tell a story by itself. They are figures at the edge of the picture, but they complete the composition. Short has become the subject of research recently, with new information being gathered by some more expert in such matters, which may give him greater presence. Maybe more photographs will emerge. But something about Harry Short, for me, says that what is most interesting about him is what we do not know. Footnote figures, those at the edge of the picture, remind us how small history is (that is, what we understand of the past) compared with all that has been left behind. How little you know, he would say with a laugh, then tell us no more.

But he would put us in touch with someone who could help.

Links

- Some of the sources used in putting this piece together were: family history sites Ancestry.co.uk and Findmypast; the British Newspaper Archive; Alan Birt Acres, Frontiersman to Film-maker: The Biography of Film Pioneer Birt Acres (2006) (this include the two other photographs of Short referred to above); John Barnes, The Beginnings of the Cinema in England, 1894-1901, vols. 1-3 (1996-98); Richard Brown and Barry Anthony, The Kinetoscope: A British History (2017); Ian Christie, Robert Paul and the Origins of British Cinema (2019) (this includes an extensive filmography with every film known to have been taken by Short for Paul); Espace.net (patents site); Denis Gifford, The British Film Catalogue, Volume 2: Non-Fiction Film, 1888-1994 (2000); Grace’s Guide (British industry and manufacturing history site); Martin Loiperdinger, Film & Schokolade (1999), The National Archives (Short’s divorce records are at J77/1008/607); Terry Ramsaye, A Million and One Nights (1926); Relli Shechter, ‘Selling Luxury: The Rise of the Egyptian Cigarette and the Transformation of the Egyptian Tobacco Market, 1850-1914’, International Journal of Middle East Studies, Vol. 35, No. 1 (Feb 2003); F.A. Talbot, Moving Pictures: How They Are Made and Worked (1912); Who’s Who of Victorian Cinema

- There is an entertaining and instructive illustrated talk, ‘“Whatever Happened at Clovelly Cottage?” The story of Britain’s first 35mm film‘, given in 2019 by filmmaker Peter Domankiewicz, on piecing together what we know of the first British film, including a recreation of it outside Clovelly Cottage today

- The following Short films are available via the BFI Player: A Sea Cave Near Lisbon (1896), Women Fetching Water from Nile (1897), Fisherman and Boat at Port Said (1897). A brief sequence from what must be one of the Niagara Falls film probably shot by Short in 1895 is cut into Rough Sea at Dover (1895). It is not impossible that Short was the operator for Opening of the Kiel Canal (1895). Another film on the BFI Player, (Breakers) (1896?) was possibly filmed by Short

- Short’s time in Portugal is documented on the Cinema Portgues site

- On the Filoscope and other flipbook technologies, see Flipbook.info

Hi Luke,

A very nice column indeed. I wholly agree with you that we need to know more about Harry Short, and, by extension, many other ‘in-between’ characters who were important facilitators in the early days of cinema. You write so well….that I am almost (almost) reluctant to note that you have glossed over the Acres relationship with Stollwerck in Germany a bit too much. I don’t know how you maintain your forward momentum in this fine narrative by bringing in a few more facts, but I do trust that your command of written English would be up to the task. The trip to Germany to ‘impress’ the chocolate manufacturer was paid for by Stollwerck, and the result was a contract negotiated in July 1895 and signed the next month for Acres to supply cameras and train cameramen for Stollwerck’s proposed new moving picture systems. Acres also agreed to design and build an automat viewer, the Electroscope, to fit Stollwerck’s needs, which he did and which Stollwerck exhibited in December 1895. It is only these six and a half months later that the Lumiere Cinematographe came out of the workshops and began its brilliant career, sidelining the Acres material (although Stollwerck remained an investor in the Acres film laboratories in the UK until about 1910 or so). I understand that would be a long diversion of your narrative, but Harry Short was there at its beginning and helped make this early work a success — more of a success, perhaps, than is indicated here. Again, I’m all for recognizing and supporting the margins……

Best, Deac

Hi Deac,

I knew I was skipping through the Stollwerck story; equally, my German is non-existent. Your comment is a welcome corrective. I started researching Short last year, abandoned the task because there wasn’t enough there to make a story, then decided to make a virtue of not knowing much.

Roll on the full and proper history of Harry Short, which we will see in time.

Dear Luke,

I appreciate your blog very much… and it was a joy to read the piece on Harry Short.

Looking forward to reading soon your post again (please due to a mistake I unscribed myself.. and I don’t find a way to make it undone.. I hope it can be sent again to my new mail address )

I wish you a fine new year 2021, and I hope you will be vaccinated in time and stay healthy,

Ciao,

guido

guconvents@gmail.com

Welcome back Guido. It’s good to hear from you. I can’t change an email address for someone signed up to follow the site, but then I can’t see your name on the list anyway, though it was there once, So I think you can just re-register using the new email address. Anyway, I hope you can keep reading. And I hope you are keeping well.

Best wishes

Luke

By circumstantial evidence, l believe the ‘maid’ in white,at Clovelly Cottage was my Grandmother,born in 1872,who had a similar upbringing as Birt,and mentored by wealthy aunt,possibly impressed Acres when interviewed for service.

Her marriage in 1900 and life in Barnet town may well have been shaped with her connection to Birt Acres,wife and children,the loss of her husband in the same year as Acres ,left her stowic,proud beautiful and tall until .her death in1954.

What was her name?

I really hope this might be true. In the 1901 census the Acres’s servant girl is named as Anne Trotter (I think, the writing is not clear), aged 15, so she is not the woman seen in the 1895 film. In the 1891 census Acres is a visitor at someone else’s house, so no clues there.

My Grandmothers maiden name was Edith Andrews,she was in service to the Vickery household in Southall in 1891prior to her Barnet employment in Park Rd,she married in 1900and had her first child,her life mirrored Birt Acres as a child..even being raised by awidowed aunt,and traveling to the west country……

Circa 1902 Birt Acres moved to Warwick Villas,almost opposite Wrotham Cottage.

Ediths employment began in 1892,when she was 20years old, so 23 in 1895.she terminated her service before her marriage in summer of 1900….so both census would have missed her time at Park Rd,although her marriage certificate says ..of Park Rd.

Isacc Cash relocated from Hackney to Barnet,and lived only a few doors from Edith her husband and new baby,this being in 1901.Edward Cashlived with his widower father,prior to being accepted for filming in India,with a missionary society.

These neighbours had a connection to Christ Church in Barnet,espescially Edith.

By 1906the Rev Arthur Hamilton Cooper resides at Wrotham Cottage,Hadley he is a Curate at Christ Church,a short cut passage Christchurch lane connects between these properties,the Trotter family of Dryham Park were the Benefactors of that Church…so perhaps young Anne Trotter may have been inlisted for Acres three child family.