To Tate Britain, to see an exhibition of the paintings of Frank Bowling, of whom (I am ashamed to say) I knew nothing before now, but to whom I am now absolutely devoted. Bowling is a Guyanese-born artist, who moved to Britain in 1953, trained at the Royal College of Art alongside David Hockney and R.B. Kitaj. A dazzlingly-talented but somewhat derivative artist in his early, figurative days, he came into his own in the mid-60s when he moved to New York and absorbed lessons from abstract expressionism. He produced large ‘map’ paintings in which he blended family images and geographical outlines of South America and Africa with fields of colour. His work over the decades becomes increasingly abstract in expression and private in meaning. The viewer gets a strong sense of a quest, of the artist setting out to understand something in the act of putting paint to canvas, yet forever having to ask the question all over again. At 85, Bowling is still painting, still asking.

As usual, I was interested in watching the people viewing the paintings. On this occasion, I took particular notice of how people were using their phones. This was an exhibition where you were allowed to take pictures of the paintings, and many of us did (myself included). We took photographs of the works, sometimes with our phones exactly framing the painting in the hope of creating a postcard-like result, sometimes allowing for a margin. We took photographs of part of the paintings, zooming in on particular details and colour effects that we liked. We took – or at least I took – pictures of those looking at pictures. Some may have taken selfie photographs of themselves before one of the paintings, though I did not see this occur. Some took photos of the labels, so they could remember what it was that they had recorded; others did not bother. We took quick snaps, carefully-composed constructions, and details, finding art within the art.

All of this was despite some of the paintings being available in postcard or print form in the shop, and the dubious colour reproduction of our phones (my photograph of a painting entitled ‘Orange Balloon’ has said balloon looking more yellow than orange). What were we doing taking these snaps with our phones?

I have been reading Nathan Jurgenson’s The Social Photo: On Photography and Social Media. It is a thought-provoking study of the nature of photography in the age of social media. Jurgenson makes the point that is wrong to think of the photography many of us undertake with our phones as being the same as traditional photography. Instead of thinking of photography as a technological practice, with the photograph as a desirable end artefact in itself, Jurgenson argues for phone photography “as a cultural practice; specifically, as a way of seeing, speaking and learning”. The social photo has become an extension of our lives as all our waking moments become “pregnant with photographic potential”. Social photos are not so much objects as means to communicate experience, a kind of “visual speaking”.

This is all interesting, and plausible. However, I began to wonder if there is not more that is going on. Jurgenson writes of social practice, but still focusses on the photograph created out of that practice, albeit something often more intuitive than deliberated, something software-driven that is then shared and seen. But was this all that the people in Tate Britain were doing?

Do we, when we take photographs with our phones, necessarily intend to produce a photograph? Obviously it is an end product, which we may look at, choose to keep or not, edit maybe, and perhaps share. But we seemed to be taking photos more immediately as an extension of seeing. There is a mental impulse, whereby we see that of the picture, or within the picture, which appeals to us, from which our mind makes us employ the phone to affirm the emotion. The phone becomes literally an extension of the eye.

Maybe there is some suggestion of Soviet film theorist Dziga Vertov‘s conception of the ‘cinema-eye’, in which the mechanical eye of the camera sees more than the poor deluded human eye:

I am cinema-eye. I am a mechanical eye. I, a machine, show you a world such as only I can see…

But no, this is something far gentler, and wholly human. We are acting on an instruction from the brain to recognise that which chimes in with, or extends, our sense of visual worth. These are images that we want, literally, to commit to memory. We may store and share the results, and may be thinking of this facility as we reach for our phone. But these are consequences. The impulse is something deeper. It is a formulation of sight itself.

The following day I went to the Royal Academy to see a small exhibition of the works of Finnish artist Helene Schjerfbeck. I first saw her work in Helsinki a couple of years ago and was hugely impressed. Schjerfbeck’s speciality was the portrait, especially the self-portrait. The central room of the exhibition is devoted to a series of her forensic self-portraits, from realistic works of her as a young woman, to near-abstract works of the artist in her eighties as she nears death. It is a most extraordinary exploration of the process of ageing, married to the paring back of art to its barest essentials.

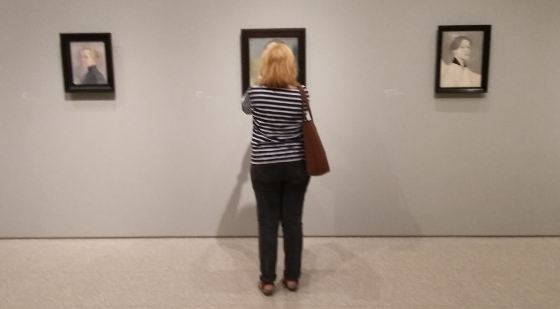

A notice outside the exhibition said that we were encouraged to take photographs, and so we did, the artist herself obligingly posing for us. There were some interesting additions to photographic practice to those seen at the Tate. Some visitors took a photograph of every single painting (or at least all of the self-portraits), intent on recording the entire gallery. Others photographed several paintings in the one image – Schjerfbeck’s paintings being much smaller that most of Bowling’s – recording groups of pictures as they worked in relation to one another. Some snapped from a distance, others loomed over to capture a detail as close as they dare. The smallness and the rawness of the paintings encouraged closeness. Most of them were portrait-shaped (as opposed to landscape), which meant that the phones were held differently. Instead of a framing action akin to usual practice with a regular camera, the phones were held vertically with the owners’ hands close together. It looked like a form of prayer.

The closeness of engagement, the stretching out towards the canvas, felt painterly in its way. The extension of seeing that the modern phone enables suggests not only capture but an urge to create. It was a form of brushstroke, making the art in the process of taking it. This is what separates the phone-camera from the traditional camera – not software, or interconnectedness, but intimacy. With a phone-camera in our hands, we have an artist’s eye.

Links:

- Frank Bowling runs at Tate Britain in London until 26 August 2019

- Helene Schjerfbeck runs at the Royal Academy of Arts, London, until 27 October 2019

- I wrote about Helene Scherfbeck and Finnish art in my 2017 blog post ‘A National Portrait‘