The founding figures of many societies are lost in myth. Perhaps the Romulus and Remus of Rome, or Moses for the Jewish people, had some grounding in historical figures, but there is no way we will ever know. In any case, the idea of a founding figure is a myth in itself, as if anywhere could have been virgin territory until some suitably noble figure, imbued with a visionary sense of purpose, first laid foot upon it.

The island of St Helena is different. This small dot of volcanic rock in the South Atlantic was only discovered in 1502. It has a founding figure who is verifiable through historical documents, one whose story is not only profoundly appropriate to the island of which he was the first inhabitant, but which has the sort of general mythic resonance which might have made it much more widely known – if only it were not true.

St Helena is located 1,200 west of Angola, 1,800 miles east of Brazil. It is 700 miles from the nearest land, Ascension Island. It is 47 square miles in size, roughly six miles by ten, though in that tiny space it manages to rise to a height of 2,690 feet. According to tradition, it was discovered by the Portuguese navigator João da Nova, supposedly on 21 May 1502 (there are now some doubts over the date), who named it after St Helena, whose feast day fell on that day.

Da Nova landed on the island, which was covered by a dense forest. He found it to be uninhabited by humans – indeed there were no large land animals, only seabirds, seals, turtles and insects. He built a wooden chapel, but then sailed on, identifying the fruitful island as a valuable resting spot for ships crossing the ocean, needing to refresh supplies. This would include goat meat, because Da Nova released a number onto the island, to multiply and provide as needed. Thus was St Helena placed upon the map (secretly, because the Portuguese wanted to keep knowledge of such a valuable location to themselves), and the seeds of its near future ruin sown.

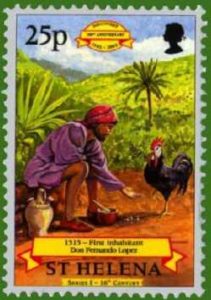

Thirteen years later, St Helena gained its first resident and true founding figure. Dom Fernão Lopes (1480?-1545), named Fernando Lopez in some places, was a Portuguese soldier who had taken part in the Portuguese conquest of Goa in India, under Afonso de Albuquerque in 1510. The conquest complete, the arch empire builder Albuquerque continued his battles elsewhere, leaving an occupying force in Goa. He returned in 1512 to find that some of that force had abandoned the defence and even joined the other side, the Muslim army of the Sultan of Bijapur. Albuquerque successfully recaptured the key fortress of Benastarim and demanded that those Portuguese who had gone over to the Muslims be surrendered to him. This was done, on the the condition that they would not be killed. The leader of these renegades was Fernão Lopes.

Albuquerque prided himself on being a man of his word. He did not have them killed, at least not directly, but he did the next worst thing. Enraged by their double crime of treachery and apostasy, he had seventy or so soldiers tortured over a period of three days. Half of them died of the experience. One the first day their hair, beards and eyebrows were pulled out and they were pulled through pig excrement up to their eyes, while people urinated on them and spat at them. On the second day their ears and noses were cut off, and the wounds left untreated. On the third day their right hands were cut off and the thumb of their left hands.

Lopes, as the leader of the group, was treated the most harshly of all. But he survived. How he managed to do so, given that he would have been traumatised by his treatment and then shunned by Goan society, is not recorded, but survive he did, on to the end of 1515, when Albuquerque died. Lopes joined a ship bound for Lisbon. What was going on in his mind can only be guessed at. He must have had a wish to return home (it is reported that he wanted to see his wife and children, though we know nothing more of them), but equally a fear of what the reception would be for a wretchedly disfigured traitor to his country and religion. He seems to have been at war with himself in some way. Whatever the reasons, when they halted at St Helena, Lopes jumped ship, hiding himself in the island forest when it was time to sail.

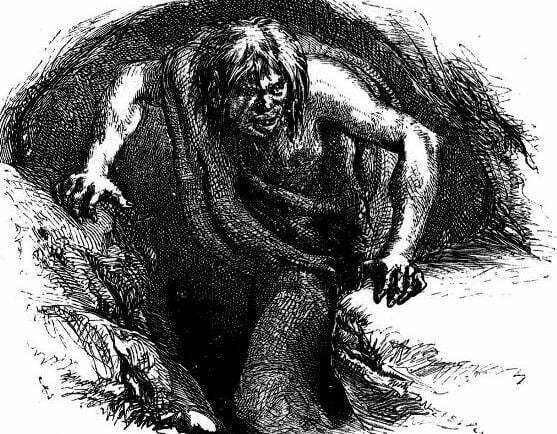

His shipmates, unable to find him, left him some food, clothes and a tinder box for fire. When they had gone, struggling to work with what remained of his arms and hands, Lopes dug himself a hollow for shelter out of the earth and covered the mouth with prickly bushes. Crippled as he was, he had enough to survive. The climate was mild, there were no predators, there was fresh water, fish, birds, goats and plentiful vegetation. The island was his. And there he would live, entirely alone, for the next ten years. Hugh Clifford, in a 1903 telling of the story, fantasises about what went through the mind of a man in such a situation:

And in place of the fellowship of his kind, which he thus renounced, of the comradeship of men who had used him cruelly, he sought solace in silent converse with Nature, the great mother. The inviolate forest towered above him; the untrodden beaches lay at his feet; no voices spoke to him save the cries of sea-fowl, the songs of birds hidden in the foliage, the busy notes of countless jungle-insects, and the sob of the sea breaking monotonously upon the deserted shores. Around him, as he sat gazing over the heaving waters, the waste of waves spread away and away to a horizon misty with heat, and that immense expanse held no suggestion of the existence of mankind … behind him the forest, filled with tiny busy life and wild things which as yet were fearless, reared its dense tangles heavenward, and seemed more remote from men than even the empty sea and sky. It was to him as though he were the only being of his kind in all God’s wondrous universe, and his very loneliness filled him with strange joy.

So it may have been, but to be alone is not to be free from company. The mind has a terrible capacity to eliminate time and space. His mind would have been filled with the world from which he had escaped only physically, and it was the resolving of what he was with what he knew that must chiefly have occupied his mind over the next ten years.

Other Portuguese ships would stop off at St Helena, but whenever they did so Lopes would hide in the forest. But the sailors would see evidence of where he was living, and would leave provisions for him, and notes saying that no harm would come to him. On one occasion, as a ship sailed away a cockerel fell overnight board. Lopes rescued it, fed it and befriended it. The contemporary Portuguese historian Gaspar Correa, our main source for the Lopes story, records that “The cock became on such loving terms with him that it followed him wherever he went, would come at his call, and at it roosted with him in the hole.”

The accounts are unclear whether he gradually made himself known to those from passing ships, or whether his hiding place was eventually revealed by a Javanese slave boy who had also escaped ship and spent time on the island, his presence strongly resented by Lopes. According to this version of the story, the slave gave himself up to the next ship that he saw and led the captain to Lopes’s cave. Lopes cried out for fear that he would be taken away, but he was given assurances that his wish to stay would be respected by all Portuguese ships. Thereafter Lopes became more willing to make himself known to those that anchored at St Helena. His fame started to spread. He was clearly viewed as a holy man of sorts, one who had suffered greatly but now dwelt in some kind of paradise, tending to crops and livestock which in turn ensured a lifeline for those engaged on hazardous journeys across those seas.

His fame reached King John II of Portugal, who asked to see him, promising him safe passage to his homeland. Somewhere around 1526 to 1529, Lopes took up this offer. His motive was not to seek home, or family, but forgiveness. He had a private audience with the king and queen, and was offered a home in a hermitage. But Lopes wanted expiation for his sins, and in his mind only one person could provide that: the pope. Remarkably, this minor soldier (possibly a member of the gentry), guilty of severe crimes and visibly punished for them, was granted a papal audience, in 1530. He was granted absolution, and given assurance that when he returned to Portugal he would not be held there but would be allowed to return to St Helena.

So it was that the shriven Lopes returned to his solitary life on the island. He had possibly been born a Jew, had lived as a Christian, then converted to Islam. From what god he actually sought forgiveness at the end of his journey, who can say? He lived out his days there, dying in 1545 – having therefore spent thirty years on St Helena, bar his journey to Lisbon and Rome.

The story of Fernão Lopes is so richly resonant. At the simplest level it is a robinsonade, a castaway narrative in the Robinson Crusoe tradition – except that Lopes’s story precedes Daniel Defoe’s novel by two hundred years. A man is abandoned on an island, free from all human society, and has to discover himself, and what it is to be human, in how he works with the world around him. It is unlikely that Defoe knew of the Lopes story (his inspiration was the Scottish castaway Alexander Selkirk), though the Javanese slave boy offers an intriguing suggestion of Man Friday. A former attorney general of St Helena, David J. Jeremiah, in his ingenious book Shakespeare’s Island: St Helena and the Tempest, argues that Lopes was a model for Caliban in The Tempest, the disfigured sole inhabitant of an island who loses it to the rude invasion of external civilised society. As Caliban tells Prospero (a model for whom Jeremiah finds in the adventurer Edward Fenton, who dreamed of establishing a perfect society on St Helena):

This island’s mine, by Sycorax my mother,

Which thou takest from me. When thou camest first,

Thou strokedst me and madest much of me, wouldst give me

Water with berries in’t, and teach me how

To name the bigger light, and how the less,

That burn by day and night: and then I loved thee

And show’d thee all the qualities o’ the isle,

The fresh springs, brine-pits, barren place and fertile:

Cursed be I that did so! All the charms

Of Sycorax, toads, beetles, bats, light on you!

For I am all the subjects that you have,

Which first was mine own king: and here you sty me

In this hard rock, whiles you do keep from me

The rest o’ the island.

What gives the history particular resonance are its themes of forgiveness (a major element of The Tempest, of course) and kindness. Lopes lived at a brutal time, when punishments such as were meted out to him were not uncommon. Mutilated faces were a familiar sight in any sixteenth century city. The life of anyone who sailed in the ships of those times, or who served in the wars, was hard and violent, with rewards for few at the end of it. Yet what we see in Lopes’ story is the great kindness of the time, at least to your own kind (Lopes seems to have been as unfeeling towards a slave as ever he would have been in normal life). Lopes was pitied from the start. His wish to escape to his island was not only respected, but nurtured. He was provided with the resources necessary for survival. His fears were understood. He was treated with gentleness and compassion by sailors, captains, royalty and the pope. As said, he came to be understood as some sort of holy man, with a special connection to God, but still there is the instinct for kindness that shines though again and again in the accounts we have of him, written by contemporaries or near contemporaries.

This in turn became reflected in the idea of St Helena itself. It was the island of shelter and rehabilitation. Ships stopped off at this abundant paradise, where water always flowed, provender was abundant and stocks could be replenished. The Portuguese used the island as a resting place for the sick, who would hope to recover by the time that the next ship stopped by. In the midst of the unforgiving ocean, this blessed island had been placed exactly where those ships sailing between Europe and the spice islands would most want to have a resting point. It was tended for a time by this extraordinary figure, who had come through great suffering to become Eden’s gardener. Long after St Helena had suffered from depredations caused by the introduction of goats (who stripped the bark off the trees), rats (who killed off many of the native birds) and man (who felled the trees), so that large patches were reduced to near desert-like conditions, the vision of the abundant island remained. Napoleon himself, when exiled on St Helena three hundred years later, had read accounts of the place which still promoted the idea of St Helena as being covered in rich, welcoming vegetation. Domiciled in the barren area of the island now called Deadwood, because the forest had been stripped away, Napoleon became all too aware of what time and man had brought about to paradise.

St Helena is not totally denuded, however. Though the coastal areas, and towards the east of the island are largely bare of vegetation, presenting unforgiving cliffs of volcanic rock to the visitors by ship, and now plane, the central parts are rich in every kind of greenery. It is easy to get a sense of how the island must have looked when Lopes first decided to escape into its welcoming forests. Where his cave was located is not known precisely, but it must have been in the valley now occupied by the small town of Jamestown, which has the island’s most accommodating bay for ships. Hemmed in on either side by huge rock walls, with a small stream running through (today called The Run), the area provided both shelter and perfect viewpoints for detecting approaching ships from afar. Lopes was the king of his island. Doubtless as more ships stopped by, more convalescents stayed, and more people (slaves usually) escaped into the forests, Lopes found himself less and less alone. Maybe he retreated further inland, though there were the gardens and orchards that he established, and the livestock he cared for, that would have demanded his attention.

Lopes was therefore not alone for all the time. Few of us ever can be, if we want our story to be known. The myth and the reality would have diverged eventually. Nevertheless, Lopes’s story is a powerful one. It would be hard to visualise, given the mutilations that he suffered, but it merits being told more widely than on St Helena itself – where it is recognised as being far more the island’s key story than that of the interloper Napoleon. It stands side by side with Caliban and Crusoe, not as influence but as co-equal. It connects us to islands, humanity, forgiveness and safe harbour.

This is the first in a series of blog posts on St Helena, following my visit to the island in March 2018

Links:

- The one book devoted to Lopes’s story is Beau Rowlands, Fernao Lopes – A South Atlantic ‘Robinson Crusoe’ (2007), which includes a translation of Gaspar Correra’s account [update: there’s now a second book on Lopes – see comments[

- The fullest account online is Hugh Clifford, ‘The Earliest Exile of St Helena‘, Blackwood’s Magazine no. 173 (1903), available via the Internet Archive

- The best place for information on St Helena is the extensive St Helena Info website, which includes a short section on Lopes

- I have published photographs of St Helena, including Jamestown and the James valley where Lopes would have lived, on my Flickr site

Interesting that you have used an image taken from http://sainthelenaisland.info/ but have not credited the site. Also you state many items of our history that current historians dispute. Perhaps try reading http://sainthelenaisland.info/discovery.htm ?

My apologies for not having credited the source of the image. I always try to do so, but the caption did not work well with the small image. I have added a caption now. Your site is of course acknowledged in the links at the end of the post.

I’m aware of the complexities around the dating of the discovery of St Helena. As analysing the historical debates was neither in my area of expertise or the purpose of the post, I kept things simple. However, to avoid being misleading I have added the words ‘According to tradition’ to the start of the sentence about Nova, and added a link to your web page.

I know also that I left out many problematic details in the Lopes story, particularly on what company he may have had with him and when. The story and the history are two different things.

Thanks, Luke. I’ve enjoyed reading all of your articles and the cricketer story got me researching – I think it may be legend but I even had someone tell me that every year blood appears “where he went over” (though how that could be, given that the Plain was extensively remodelled by the Royal Engineers in the 1970s, I can’t see). Are you still on St Helena? If so please pop into the Moonbeams shop any weekday 9-12 and we can meet. If not, next time!

Hi John,

Glad you liked the articles, and many thanks for your website, which is such a reliable and engaging source of information. I particularly admire any site that comes with a subject index.

I suspect too that the cricket story is a legend. When Francis Plain was remodelled in the 1970s, was the ground made smaller, or the slope before you get to the drop changed?

Sadly, I was only on the island for two weeks and I am back in the UK. And my self-catering place was just behind Moonbeams. But I hope there will be a next time.

you may be interested to know that my book on Fernao Lopes (The Other Exile) was published by Icon Books in 2017. You may enjoy reading it.

Thank you for letting me know – I shall certainly look out for it. Here is the link to it for anyone else interested to do the same: https://www.amazon.co.uk/Other-Exile-Fernão-Helena-Paradise/dp/1785781839/

I have now read A.R. Azzam’s book on Lopes, The Other Exile. It is excellent – a remarkable piece of speculative but disciplined historical investigation, and a first-rate read. I can warmly recommend it to anyone.

I can absolutely recommend the book. It seems well recearched, and it is an extremely fascinating story,

Hello Luke, thank you for your interesting and informative Article! I wrote a blog post about Fernao Lopes (in german), and your article was very helpful in my research. I also used some of your beautiful Photos, I hope the credits are correct, otherwise please drop me a note.

You can find my article here: http://dampierblog.de/fernao-lopes

You may want to translate it with google, although I recomment DeepL, which does the job even better to my opinion (I tested them both with my text).

A second article about the sources (including your article concerning the Shakespeare connection) and misc remarks about the story is about to be finished, I hope to publish it in the next few days.

kind regards, Dampier

Thank you Dampier. That’s a great article, which translates well into English (Google Translate calls Lopes a ‘nerd’, DeepL calls him an ‘oddity’, which is better all round). I look forward to seeing the second article – do post the link here if you can. The Shakespeare connection is well worth highlighting – David J. Jeremiah’s book Shakespeare’s Island: St. Helena and The Tempest is excellent.

The Lopes story has all the great qualities of myth and so should be told again and again.

And I’m glad you like the photos (you picked a favourite of mine).

Luke