The build-up to a show is always a part of the show. The title, the publicity photos, the names in lights, the walk down a corridor or up flights of stairs, the taking of one’s seat, the buzz of anticipation, the drawing back of the curtains. At the Panorama Mesdag in The Hague, some of this is in evidence, but with an extra twist.

The exterior of the building gives you the name; the guide book entices you with the information that this is the oldest surviving panorama still to be found in its original, dedicated location. Since 1881 people having been going to the very show that you will now experience. You proceed through a long corridor with a timeline and examples of the works of Dutch artist Hendrik Willem Mesdag (1831-1915), an accomplished and in his time acclaimed producer of marine paintings, who was the chief creator of the panorama you are about to see. Not the only creator, you are told, for among his several collaborators was his wife Sina (Sientje) Mesdag-van Houten (1834-1909), herself a painter of some skill. Examples of her works are also on display.

Your appetite suitably whetted with facts, names and images, you approach the entrance to the panorama. Here lies the twist. You are being set up. As you proceed down a dark corridor, the darkness enlarges the pupils of your unwitting eyes. You climb a spiral staircase, separating the senses from the familiar world you are leaving behind while building up expectations. You do not know where you are but you know where you are going.

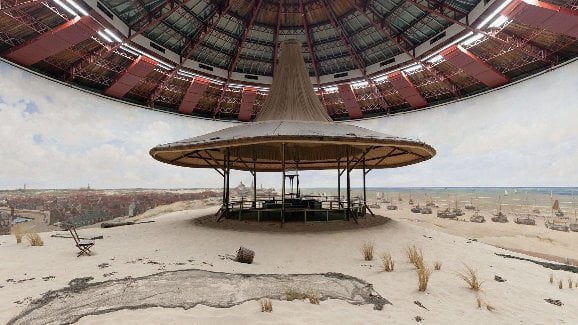

You step out onto a circular viewing platform and what is there before your widened eyes is utterly overwhelming. You have stepped into infinity. The space is so much larger than you are expecting, the brightness such a shock to the senses. A 360-degree image surrounds you, to which there seems to be no top or bottom. You have become God-like, the viewer of all things, totally immersed in the artwork that envelops you.

What you see before you, in every direction, is The Hague’s seaside resort of Scheveningen, reproduced in meticulous detail. You are positioned as though on the Seinpost, the highest sand dune in Scheveningen, and indeed what you see just below you is real sand that leads down to the circular painting. There is The Hague with its prominent church towers to the south; west, and in front of you, the lighthouse, the long beachfront busy with shipping; north, the Von Wied pavilion, hotels and the municipal bathhouse; east, some open country and the new steam tram line. There are boats, people, buildings, the sea rolling in, and above the endless, clouded sky.

You start spotting the details (there are binoculars available). You detect landmarks, but what you really want to see are people, and the stories that they promise. There are fishermen attending to their nets before heading out for another catch. Along the sands there is a procession of cavalry undertaking exercises on the beach. There are sea bathers emerging from protective bathing coaches. The fashionable promenade along the shore. In the town, household sewage is being collected by horse and cart. There is a ghostly figure on the side of one of the houses – an unfinished piece of the painting or an actual ghost? There is a painter at her easel, a parasol above her, a servant (presumably) looking inquisitively over her shoulder – surely the painter is meant to be Sina.

The eye is continually drawn across the canvas, to pick out such features and have them play with the imagination. But there is more going on. Mesdag was unhappy with the encroaching industrial age and his painting reflects this. At the edges of the view one sees steamships out at sea, while traditional sailing craft are ashore. The steam tram speeds along in the distance, with a trail of white smoke. More smoke pours out of industrial chimneys. Where once there was nothing but rolling dunes, now hotels and entertainments for the growing number of tourists are being built. What appears at first to be a celebration of stillness is actually a record of change. To judge from the sails and waves by the shoreline, and the smoke trails of the chimneys and tram, there are opposing weather systems on display. One could say that such smoke trails are simply created by objects in motion, but the smoke coming out of the chimneys trails in the same direction. The inner world is blowing one way, the threatening outside world is blowing the other. There is profound disharmony in this supposedly idyllic view.

Hendrik Mesdag came from a business family that had artistic links – Lawrence (Lourens) Alma-Tadema was a cousin of his. He was able to indulge in his passion for painting thanks to his wife’s fortune, gradually building up a reputation through his seascapes and moving with ease among the cultural elite of the Netherlands. He remained a businessman, however. When he was approached by a group of Belgian investors to create a marine panorama he welcomed the opportunity, when others of his profession might have sneered at being involved in such populist fare.

Panoramas, or wide-angle views of a subject presented as public entertainments, had been around since the 1790s when Irish artist Robert Parker applied the term to his innovative large-scale paintings of Edinburgh. He had worked out how to maintain a sense of perspective when presenting a large-scale image over a curved surface. He opened a Panorama building in London’s Leicester Square in 1793. Visitors would stand on a central platform and view the semi-circular world before them.

The huge success of Barker’s Panorama led to many imitators and variants. There were semi-circular and 360-degree panoramas (Cycloramas), moving panoramas, Dioramas (where the panoramic painting was static but the audience was moved round on a turntable), Cosmoramas and so on. They could be accompanied by lecturers, or music and lighting effects. By the time Mesdag was invited to produce his panorama, the public thirst for such entertainments was on the wane, and though the Scheveningen display gained much praise (no less a visitor than Vincent Van Gogh said of it, “the only shortcoming of the painting is that is has no shortcomings”), the company that ran it went bankrupt in 1886.

Thereafter Mesdag took over the business (the panorama remains to this day in the hands of the Mesdag family), partly because he must have felt there was still a business opportunity there, but maybe more because he knew that this was his masterpiece. 114.5 metres in circumference and 14.4 metres high, a total surface of 1660 square metres, the Mesdag panorama is as huge in its imagination as it was in execution. Technically adroit, touristically satisfying, it is also a profoundly accomplished comment on the construction of reality.

Panoramas (and their variants) are recognised as antecedents of, or analogues to, the cinematic experience. There is a large screen that must dwarf the viewer; the immersive nature whereby the viewer becomes wholly absorbed in the world placed before them; the seeking out of stories at a macro (the overall narrative) and micro (the stories to be found within) level; the shock and delight of seeing reality recreated. One sees that cinema, and the immersive visual entertainments that have come after it (television, IMAX, virtual reality), are part of a human compulsion to accept a visual recreation of reality and to live (for a time) within it. Such spectacles become our dreamworlds and help us orient ourselves within the true world to which we must return. Here is the place, which comes to life because we are there to witness it.

Viewing the Mesdag panorama from every point of its central platform, from shoreline activity to the limitless skies, a particular film came to my mind – The Truman Show. In Peter Weir’s ingenious 1998 film (plot spoilers ahead), Truman (played by Jim Carrey) is the unwitting star of a reality TV show. The show is set on island, Seahaven, constructed within a gigantic studio, with fake buildings, roads, communications, landscape and people (all played by actors), which only Truman thinks is reality. Born and raised in Seahaven, he yearns to travel (Fiji is his dream destination), but loved ones ask him why he would ever want to leave, and a manufactured boating accident in which his ‘father’ appeared to drown, has intentionally left Truman with a deep fear of the sea.

When his ‘father’ reappears, years later, Truman starts to piece together what actually is happening around him. He overcomes his fear of water to sail away single-handedly from the island. Having weathered artificial storms sent by the desperate producers, Truman proceeds serenely over a calm sea to the cloudy horizon – into which his yacht collides, piercing the fabric of the world that has contained him. Walking along the edge of this world, he finds a set of stairs and door. He makes his escape to who knows what, cheered on by an unseen viewing public.

Mesdag created a similar all-encompassing world that all but invites us to sail away from the centre, where we will eventually run into the limits of illusion. Our dreamworlds satisfy only insofar as they appear to be infinite; once we discover their falsity, we must break through. Mesdag painted an idealised image of a treasured, unchanging location in which its Dutch visitors might wish to reside forever, but surrounded it with the agents of change. The dreamworld, by straining to keep out reality, must inevitably destroy itself.

The Panorama Mesdag too has its piercing moment. When you exit via the same stairwell, in a corridor leading towards the outside world there are two portholes through which you can see the previously-hidden bottom edge of the panorama. Reality intrudes.

The Panorama Mesdag is the most astonishing experience. Images of the work, even in its laid-out-flat entirety, cannot give any real sense of the shock of stepping up out of the dark and finding oneself confronted by an infinite view. It is so unreally real. You could stay there forever, because why would you ever want to leave? But, logically and inescapably, you must.

Links:

- The Mesdag Panorama site (in Dutch and English) includes an explorable representation of the panorama, with background texts on some of the highlights, and audio tour

- There is also the Mesdag Collection museum in The Hague, housed separately to the panorama, which contains Henrik and Sina Mesdag’s collection of nineteenth-century art

- For a useful, illustrated, historical account of panoramas, see Markman Ellis, ‘The Spectacle of the Panorama’, https://www.bl.uk/picturing-places/articles/the-spectacle-of-the-panorama

- Other circular panoramas on public display include the Thun Panorama in Switzerland; the Panorama of the Battle of Waterloo in Belgium; the Racławice Panorama in Wrocław; the Gettysburg Cyclorama in Gettysburg, Pennsylvania; and the Borodino Panorama in Moscow

Fascinating – wish I had known about the Mesdag Panorama when I was there for the World Equestrian Games in 1994. My friends and I stayed in in a rather quaint hotel in Scheveningen.

Hello Linda. Peculiarly enough, I have seen the imagined Scheveningen but not the real place as yet. It would be good to go to the same Seinpost dune location (there’s a restaurant there now) and look out in all directions.

One scene in my film ‘ A Strange Love Affair’ (co director: Paul Verstraten)is situated in the panorama. My DOP was Henry Alekan. Notwithstanding his talent and experience he was not able to give a good impression. It stayed flat! As it was a low budget film, we had not much time to shoot. Or to wait for a good natural (?) lighting!

A version of this blog post has now been published in Spaces: Exploring Spatial Experiences of Representation and Reception in Screen Media, edited by Ian Christie and published by Amsterdam University Press. You can purchase the book, if you are quite rich, in hardback, or there is a free PDF version available via https://library.oapen.org/handle/20.500.12657/87674