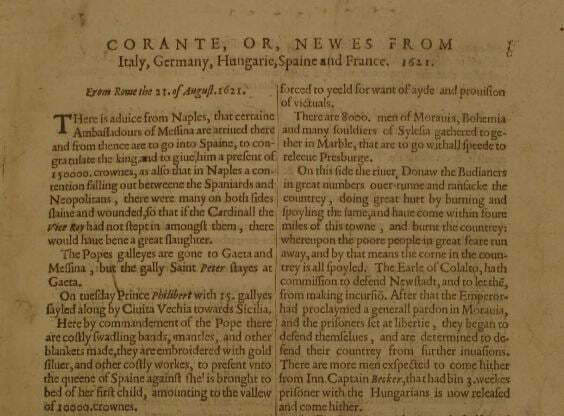

In two years’ time, it will be the four hundredth anniversary of the newspaper in this country. The first known newspaper in English, Corrant out of Italy, Germany, &c. was published on 2 December 1620, in Amsterdam. A year later, on 24 September 1621, the first newspaper was published in this country, the Corante, or, Newes from Italy, Germany, Hungarie, Spaine and France.

These newspapers survive at the British Library, and, looking at them, they are remarkably close to the newspapers of today. What we see is a sheet of paper: portable, foldable, shareable. There is a masthead with the title of the news publication. There is a date – strictly speaking, a date for the first story. There are stories, arranged in columns, with a shared currency. It gives a shape to the news, with the promise of more to follow.

The newspaper has been a remarkably successful publishing model, sustained in this country, after an unsteady start, for nearly 400 years. The newspaper and its prints variants flourished, with the inhibitions of censorship, taxation or regulation failing to halt their progress. The newspaper informed, entertained and helped define the nations and regions that it served.

The newspaper went largely unchallenged as a medium of news for nearly three hundred years. Certainly there were variations on the form, from periodicals to broadsides, and changes were brought about in size, illustration, distribution patterns and so forth, but essentially the news meant the newspaper.

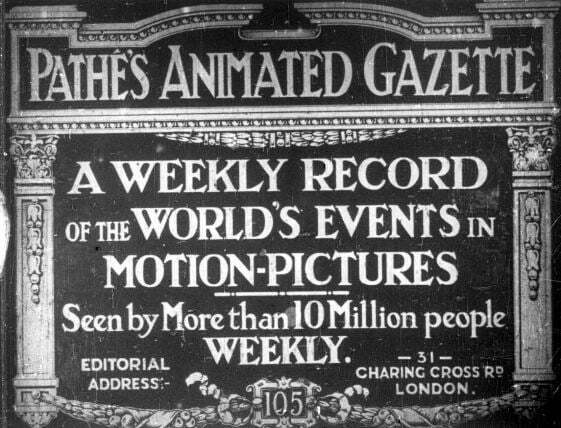

That changed in June 1910, when a wholly new news form was published – the newsreel. One can argue over the significant date, for newsfilms of a kind preceded newsreels just as there were news sheets and other news publications before there were newspapers. But with Pathé’s Animated Gazette, issue one of which was shown in cinemas in June 1910 and weekly, then bi-weekly thereafter, something changed. This was news on a new medium, that not only communicated the news in a different way but had to be consumed differently, by an audience sitting in a cinema, unable to control the order of stories in which they appeared nor the time they might want to spend on each one.

The newsreel did another revolutionary thing. It invited the audience to widen its understanding of the news, even to have a measure of control over it. Owing to the complexities of film processing, newsreels could not be published daily. They were published bi-weekly, matching the common pattern of cinema attendance (i.e. most people were going to the cinema twice a week), and deliberately chose news stories which had featured in the newspapers previously. You had read the story, now you could see it in motion. You the audience could combine these media together to enrich your understanding of the news, if you so wished.

Newspaper owners were swift to react to this. In the USA, William Randolph Hearst rapidly bought into the newspaper market, creating Hearst-Selig News Pictorial in 1914. In the UK, Edward Hulton, owner of The Daily Sketch newspaper, bought the Topical Budget newsreel in 1919. Lord Beaverbrook of The Daily Express became co-owner of Pathé Gazette in the 1920s. Hulton and Beaverbrook wanted to own the totality of the news.

But the news was spreading, increasing audience power while making it much harder for the news barons to control every manifestation of the phenomenon of news. The BBC introduced news bulletins on 23 December 1922, under government licence. It lay outside any possible control of the newspapers (though originally the BBC was restricted to using news agency copy only), and swiftly challenged them through daily publication and command of the public space. Radio added a new dimension: live reporting, collapsing the time difference between news event and news consumption.

Radio also offered sound, of course, which the newsreels adopted around 1930. News could now be read, or seen, or listened to, and with each innovation the newspaper lost that much more of its claim to the totality of news, while audience power grew with the increase in choice.

Next came television. The first BBC television news programme, in January 1948, was a newsreel in form and name – Television Newsreel, while the new medium owed much in its early years to its parent medium, radio. As with radio in the UK, it originally owed its existence to government licence, and added to the trump cards of frequency, domestic space and live reporting the particular power of the newsreader.

News now had a human face, that spoke to you the viewer as an individual as well as to the mass. It added to that sense of reassurance that news publications existed to provide. Danger and calamity were what was happening to other people. The fact that you were there to read the news, or to have it read to you, implied that you were safe.

Then came news on the web. Traditional news organisations were extraordinarily slow to grasp the implications of the Internet. Confident in their well-established models, in the audiences that were assumed to be loyal to them, and in the advertising revenue that sustained them, they were profoundly shocked – and continue to be shocked – by this mode of distribution and communication which upturned their every expectation. A fierce rearguard action is being fought, defending traditional newspaper values against the freewheeling digital behemoths Facebook and Google, but the balance of power has shifted irrevocably.

News stories now filter through a myriad of networks; the advertising money has moved to search; choice has expanded beyond any reckoning; the timetables around which had traditionally structured itself have gone; and the audience has become all powerful. The traditional news world has been disaggregated, and we are all – producers, readers, advertisers, regulators, legislators – trying to work out how to put the pieces back together again. All that is certain is that the Internet makes the news, because it has become the lifeline on which all news production and news communication now depend.

News in the UK has changed greatly over the past 100 years, in medium, range, extent and ownership. Today much of the understanding on which news has been based, the contract between publisher and reader, is being challenged. Political upheaval combined with the mushrooming of digital outlets, combined with growing audience power on what is accepted as news, has made collecting the news all the more challenging – and imperative. What is the news now, and how do we collect it?

The British Library, until recently, has not collected the news – it has collected newspapers. As part of its function as the national research library, and as an outcome of Legal Deposit legislation, the Library (or the British Museum before it) has had the power since 1869 to request one copy of every newspaper issue published in the UK or Ireland. Just the one edition is taken where there are multiple editions of a title, usually the latest edition.

Between roughly 1822 and 1869 copies of newspapers were supposed to be sent to the Stamp Office for reasons of taxation, and these copies subsequently made their way to the British Museum. Consequently the collection is comprehensive from 1869 onwards, and nearly so for 1822 to 1869, though comprehensive is, in our case, a relative term.

Prior to 1820, the Library has been dependent on acquisitions and donations, mostly notably the newspapers, news sheets and news books from the Civil War period collected by bookseller George Thomason, and the Burney Collection of newspapers 1603-1818, collected by the Reverend Charles Burney. As a result of Legal Deposit, donation and acquisition, the collection amounts to some 60 million issues, or 450 million pages, though that is a figure derived from counting the number of volumes held, and in truth no one can really say exactly how many newspapers the British Library holds.

We do know how many are coming in, however – currently we take in 1,200 titles every week – that is, a combination of dailies and weeklies received under Legal Deposit. The figure is down from the 1,400 or so we were taking in only a couple of years ago, but, for the time being at least, this is remains a country with a remarkable appetite for newspapers.

Around a third of the titles in the collection are from overseas. Relatively few foreign newspapers are now collected, owing to storage issues and the availability of electronic newspaper resources, but historically there was collecting from many countries, notably from Empire and then Commonwealth countries which were received through colonial copyright deposit.

But what of the other news media? There is no Legal Deposit for sound or moving image in the UK. The Library incorporated the National Sound Archive in 1983, but its collection has been created through acquisition, special arrangements with publishers, off-air recordings and the recording of live performances and interviews by the Library itself. News, until recently, was not part of its collecting remit, though its radio collections did include some news broadcasts.

For television, the British Library deferred to the British Film Institute (BFI), which has collected the medium selectively since the late 1950s. The Broadcasting Act of 1990 brought in statutory provision for a national television archive, paid for by the television companies, driven by off-air recordings of programmes as they were broadcast. This archive is maintained by the BFI, and since the mid-80s it has been recording on a daily basis television news programmes from the main terrestrial channels.

In 2010 the British Library re-introduced off-air recording, taking advantage of an exception in UK copyright which enabled it to record broadcast programmes for the purposes of maintaining an archive. It had previously recorded radio and TV programmes up to 2000, mostly on musical themes. Now the emphasis was on news. This was driven by a wish for the Library to build up its moving image capability, and in response to a gap in archival provision. Although the BFI was recording the main terrestrial television news programmes, most news programmes from the 24-hour news channels were not being archived by any public body. There was an opportunity to become a television news specialist, adding radio news as well to the mix, to provide a service to researchers not available elsewhere. It was also recognition that television and radio news made for a logical extension of the Library’s news collection. Newspapers were no longer enough.

In 2013 the Non-Print Legal Deposit Act was passed, permitting the British Library, in partnership with the other Legal Deposit libraries of the UK and Ireland, to collect electronic publications, including websites, the same as for print. This has been a complex and gigantic undertaking, with the number of files now archived running into the billions, dwarfing in size the Library’s physical collection.

Most of the websites on the UK Legal Deposit web archive are captured once a year. That is, a snapshot record of a website is made as it appears at one point in time, with all pages linked to a root URL. This is not suitable for news, where so much can disappear quickly, and where there is a research imperative to see the news as it was made available, at regular points in time. We need web news to be archived like print newspapers, because print newspapers have established the model. So, from 2014, we have been capturing news websites on a regular basis, usually weekly, but daily for the national daily newspaper sites and news broadcaster sites.

It has taken a while to build up, but we are currently capturing some 2,000 web news titles on a regular basis, in collaboration with the other Legal Deposit libraries. This has included perhaps the most radical shift yet in our news collecting strategy, because as well as archiving the websites of the recognised news publications, around half of what we are archiving has been hyperlocal news sites.

Hyperlocalism, a local publishing movement which began in the USA and has taken off greatly in the UK in the past four years, means that anyone can be a news publisher. Anyone with a bee in their bonnet or a feeling that the news in their street is being overlooked can sign up for free to a WordPress site, give it a newsy title, and start publishing. And, if the British Library gets to hear of them, we will start archiving them. We do not discriminate.

There is no definitive list of hyperlocal sites in the UK (though there are two directories that list many: Local List, and Cardiff University’s Centre for Community Journalism’s directory of hyperlocals). Nor is there any comprehensive listing available of standard UK news websites. Consequently we do not know what percentage of the UK’s news websites we are archiving, though we are confident at least that it is a good majority.

There are many problems with the archiving of web news, however. Firstly, there is the sheer vastness of the web. No one can say what the true size is of a phenomenon which is in a continual process of change, but in a recent talk web archivist Ed Summers calculates that the Internet Archive, which said in 2016 that it has saved 510 billion web captures, might by this have collected just 0.39% of the web. We can see something of the mania of trying to capture the ever-changing web in the Internet Archive’s hourly captures of the dailymail.co.uk (known as Mail Online in the UK). It is too much to comprehend, certainly too much to archive. The comprehensive archive of what is published can no longer exist.

Secondly, owing to purely technical reasons, the Library is not always able to capture the audio and video elements of news sites, and even if it can capture them it is not always able to play back the results. Next, there used to be a simple correlation between a printed newspaper and the website that shared its name, and often its content. Increasingly the two are diverging, not just in content, but in title and scope. Single websites increasingly represent several regional newspapers where costs need to be cut. Newspapers are also being replaced by web versions, most prominently The Independent, which exists no longer in print but continues its digital existence as a facsimile version of the print title, as well as the independent.co.uk website and the indy100 spin-off site.

A few years ago, many newspapers made a PDF of their newspaper available on the website, but now a far more complicated picture exists, with a combination of digital outputs and many newspapers turning to aggregators such as PageSuite to provide digital access for them. Collecting newspapers digitally, which the Library does not currently do but is investigating, will not be a simple case of matching like for like. Whatever future collecting model the Library may pursue is bound to include a measure of print newspapers, not least because we will want to continue to collect a core of newspapers as print out of respect for a 400-year-old medium, for as long as there continue to be print newspapers. But one thing is certain – the world of digital news is different to that of physical news, and we will have to obey the rules of digital.

The current collection comprises the following: 60 million newspapers, 2,000 websites captured a total of 400,000 times, 85,000 television news programmes and 40,000 radio news programmes. Each week we take in 3,500 UK news publications of one kind or another. The news publications are collected through a combination of Legal Deposit, copyright exception and licence.

All of this is expressed in the key principles underpinning our news content strategy:

- The Library’s news offering incorporates the full range of news media – newspapers, news websites, television news, radio news, and other media

- The Library’s news content comprises primarily news most relevant to UK users, meaning news produced in the UK or which has had an impact on the UK

- The Library also collects or connects to selected overseas newspapers, now primarily on microfilm or digital, according to availability and with focus on areas of research interest

- The content strategy for news media is underpinned by Legal Deposit collecting, both print and non-print, but includes audiovisual media that lie outside Legal Deposit

The challenge for the Library will be how to bring these different news media together. That is why our news strategy focusses strongly on data. Commonalities of data – particularly date, time and place – will be essential for linking together different news stories. Other libraries are already experimenting with this, the Royal Danish Library for example, with its Mediestream service that brings together newspapers, television and radio.

To achieve such integration it will be essential to link up not only by date but keyword. We already capture subtitles for television news programmes where these are available; we are now experimenting with speech-to-text transcriptions of radio programmes. We will eventually be able to offer full text searching across each of the news media. The quality of such transcriptions will vary according to source, so an essential next step will be to extract entities, or themes, from these transcripts, using a shared set of terms.

So I will be able to ask of a future resource discovery system, show me everything you have relating to Brexit between 1st and 31st December 2018, and there will be there newspaper stories, the television news stories, the radio stories and the web stories, all of them indexed automatically, as well as books, papers or other media produced at that time which will enrich the picture of what the news was on this one topic at that particular time. All those objects must be born digital or to have been digitised, so our collecting policy must be digital.

There are other news media. The Library is looking at podcasts, which certainly fall under its sound and news collecting remits, not least because all the major newspaper titles and news broadcasters are producing podcasts. No commitment has been made as yet, but we have started capturing some sample news-based podcasts.

The area of current news that we get asked about most is social media. We are not archiving Twitter, firstly because it is an American company and so falls outside our UK web archiving remit. The Library of Congress took on the task of archiving Twitter, though a year ago it announced that the task was proving too great and that it would only be archiving Twitter selectively from now on. The British Library archives some Twitter feeds where these have a British focus, a number of which are news-related, but it is a tiny drop in a vast ocean.

Twitter highlights the challenge we now face in trying to collect the news. It is not just about the vast scale of the archives, but about their meaning. As I wrote earlier this year:

The archiving of Twitter is a logical impossibility. There is no single Twitter out there that might be consulted equally by any of us. There are over 300 million Twitters in existence. Each person signed up to the service selects who they will follow and what topics interest them. No one person sees the same Twitter as the next. It is universal and absolutely personal at the same time, which is the key to its particular power. No archive can replicate this, because it must convert the subjective into the objective.

The subjectivity or personalisation of news is going to present us with the greatest collecting challenge. If everyone sees the news differently, how do we collect it? Once it was understood that a news object such as a newspaper was read in the same way by the same set of people for whom it was intended, usually defined by geographical location or political persuasion. But does that apply in a wholly digital world?

Those who once saw themselves as newspaper publishers now view themselves as news publishers. News is gathered and composed digitally, and then transmitted through a variety of media, one of which – for the time being – remains the print newspaper. To get at the heart of news, to collect it fully, one might want to collect not the published forms but the individual digital elements and the content management systems that hold them. Then one could recreate the news in the various forms in which it was be distributed at any given point in time – as print, website, mobile and so on. Collecting news as publications has been fine for 1620 through to, maybe 2020. But what after then?

John Carey, in his introduction to The Faber Book of Reportage, makes an intriguing argument about the nature of news. Firstly, he says:

The advent of mass communications represents the greatest change in human consciousness that has taken place in recorded history. The development, within a few decades, from a situation where most of the inhabitants of the globe would have no day-to-day knowledge of or curiosity about how most of the others were faring, to a situation where the ordinary person’s mental space is filled (and must be filled daily or hourly, unless a feeling of disorientation is to ensue) with accurate reports about the doings of complete strangers, represents a revolution in mental activity which is incalculable in its effects.

Carey considers what it was in the mindset of pre-communication age humans that reportage replaced, and he suggests that the answer is religion. He continues:

Religion was the permanent backdrop to [man’s] existence, as reportage is for his modern counterpart. Reportage supplies modern man with a constant and reassuring sense of events going on beyond his immediate horizon … Reportage provides modern man, too, with a release from his trivial routines, and a habitual daily illusion of communication with a reality greater than himself … When we view reportage as the natural successor to religion, it helps us to understand why it should be so profoundly taken up with the subject of death … Reportage, taking religion’s place, endlessly feeds it reader with accounts of the deaths of other people, and therefore places him continually in the position of a survivor … [R]eportage, like religion, gives the individual a comforting sense of his own immortality.

There is plenty to challenge in Carey’s suggestion of reportage as being the natural successor to religion. There are different religions out there, and religion did not disappear with the emergence of public news forms. He also blends mass communications, reportage and news, though they are not the same as one another. But his theory is richly suggestive. One thinks of John Donne, writing in 1611 in his poem ‘An Anatomy of the World – The First Anniversary’ of changing ideas of the universe, “’Tis all in pieces, all coherence gone / All just supply, and all relation”. Ten years later the country’s first newspaper would appear.

Carey’s insight also provides an interesting mechanism for considering the nature of news today.

Published, public news has fed curiosity, has helped to solidify our sense of belonging, and has provide a sense of reassurance. It has profoundly influenced our sense of time. The question is whether our new world of news will continue to do the same. News is a constant, but the forms in which it is transmitted must change, and they could be in the process of changing quite radically. The trust in the definable news publication to tell us who we are by relaying what we want to know, could be disappearing. The need for assurance will remain, however, so what will provide it? The increase in the personalisation of news, the logical extension of which is to make everyone their own news editor, hardly seems a recipe for the sort of assurance that leads to a settled society.

Or maybe we are entering a post-news era, with a changed sense of reality, an age without reassurance. My personal definition of news is that it is “information of current interest for a specific audience”. It’s a flexible construction, but what happens when I no longer feel certain to what audience I belong? Maybe an age of supreme individuality is underway, in which I no longer feel a part of any audience, or else there are so many audiences to which I could be said to belong that the concept becomes meaningless. It is a world lived in a continuous now, where the past is losing its meaning, and where everyone thinks themselves immortal. That could be the end logic of an entirely interconnected world.

Despite the alarmist cries from some quarters about disinformation and the undermining of the news media as we have known them, these remain fringe concerns. The vast majority of people trust the established news media. They like their local newspaper, or at least the idea of there being one. They watch the same TV news programmes in their usual slots, they listen to the familiar radio news summaries. The urge for local identity is driving our politics, so there is little evidence for saying that we no longer know who we are or where we belong. We still need the reassurance of news. The post-news era is still some way off. Perhaps it will always be some way off.

Meanwhile the British Library’s collecting policy must be to collect what it can, by the mechanisms that are available to it. It wants to collect across the different news media, through a combination of Legal Deposit, copyright exception and licence, augmenting what is still its core news collection, newspapers. Everything must be built around the newspaper, for the time being. Our revised news content strategy, currently in development, has the subtitle, “moving from a newspaper collection to a news collection”. It sounds reasonable enough. We must do what we must. But the world of news may be moving beyond us; beyond the British Library, or any of us.

This a shortened version of a talk I gave at the Media History Seminar, Senate House, on 4 December 2018. It was originally published on the British Library’s Newsroom blog on 16 December 2018, but I have chosen to reproduce it here as well. A PDF copy of the full text, with footnotes, is also on my website, here.