At the British Library (the institution which kindly helps me keep body and soul together) we regularly make promotional videos. They are snappy little numbers, designed to show what a bright, inviting and relevant place the Library is. The editing is brisk, the graphics float informatively over the screen, and the music is toe-tapping.

Yet you feel that when any production company is handed a commission to make a promotional film for us that their heart sinks. How on earth does one make an interesting film out of a library? It is nothing but books and manuscripts, shelves upon shelves upon shelves, quaintly amusing staff, and a solemn clientele all of whom are sitting down, reading. There can be little more joy involved in the production of such videos than instructional guides for factory processes, or advertisements for banks.

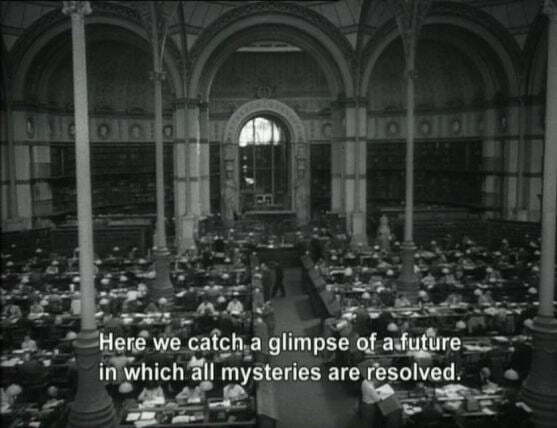

And yet, what if your filmmaker is a poet? The finest documentary made about a library – perhaps the only fine one ever – is Tout la mémoire du monde, produced in 1956 by Alain Resnais. Ostensibly an film informing us about the operations of the Bibliothèque nationale in Paris, in practice it is a disquisition on fear and memory. Over lingering tracking shots of unending, Borgesian corridors of books, the commentary interweaves factual information with thoughts on the human motives behind such a vast undertaking. Humans dread forgetting, so they collect, yet they dread being overwhelmed by the knowledge before them. They strive to catalogue and thereby to gain mastery over that which cannot be controlled, not least because it is never-ending. The books are released from the vaults where all are equal, to the reading rooms where they become personal, and where the readers collectively engage upon an activity which seeks to find an answers to all the questions that there may be, and thereby discover happiness.

Perhaps one of the makers of the British Library’s promos will go on to make his or her L’Année dernière à Marienbad – they may be dreaming so themselves. At any rate I encourage them to look out for the BFI’s DVD of Céline et Julie vont en bateau (Céline and Julie Go Boating), made by the late Jacques Rivette, on which Resnais’ masterly film is included as an extra.

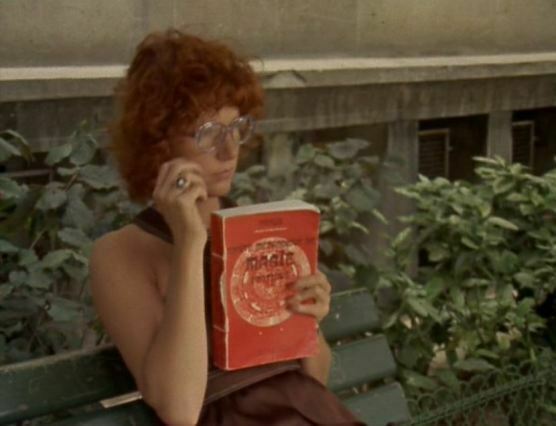

But what is it doing there, accompanying Rivette’s fantastical and very long 1974 film about two women’s adventures through Paris, which lead to uncovering and taking part in the stories that lie within a hidden house? Well, it’s because Céline and Julie go Boating is the ultimate library film. Julie (played by Dominique Labourier) is a librarian; Céline (Juliet Berto) is a magician. She’s not a very good magician, nor does Julie appear to be much of a librarian (she spend her time smoking, playing with tarot cards and playing with the ink of a book stamper), but it’s not the reality but the imagined that counts. Céline and Julie merge into one in any case – the film opens with Julie (reading a book of magic) chasing after Céline after the latter drops something (in imitation of Alice in Wonderland); it ends with the same scene but the roles reversed. They each play the same role in the film-within-a-film. They have interweaving identities. It’s a film about the magic underlying the real world, and about how stories all interweave with one another, in a labyrinthine journey through the imagination – much like a library.

The film spends relatively little time in the library where Julie works (they return to it later on to steal some books). Instead it plays upon the idea of the library as a metaphor for the world of stories. Céline and Julie Go Boating (the title alludes to a French term for shaggy dog story, though they do actually go boating towards the end) is about storytelling. It references Lewis Carroll and Henry James (the central film-within-a-film is based on two minor James stories, but there is something about the trapped child theme that reminds one of What Maisie Knew). It mimics numerous modes of film genre, or storytelling techniques, as well as specific films – Jean Cocteau’s Orphée, Věra Chytilová’s Daisies, Louis Feuillade’s Les Vampires.

Céline and Julie Go Boating is endlessly fascinating for how it plays with narrative and logic. At just over three hours long it is a challenge for some audiences – when I first saw it at a film society screening many years ago, half the cinema had walked out long before the end – especially when it is not always clear what is happening. Céline and Julie’s conversations do not always flow logically (sometimes one seems to give an answer before the other asks the question, while other talk is constructed among seemingly absurdist non sequiturs). Viewing it again recently I found the Jamesian film-within-a-film a bit tedious at times, and felt that the film lost something of its special quality when things in its later stages started to make sense. But a three-hour, semi-improvised film is bound to have its weak points. Other films are nothing but weak. Céline and Julie Go Boating is an adventure through mind and memory – which is what connects it to Resnais’s film, and what makes it the perfect library film. It’s not the time spent among the books, but the time spent inside them.

Documentarists may have struggled with libraries, but fiction filmmakers have long relied on them. Libraries looms large in Three Days of the Condor, The Name of the Rose, Citizen Kane, Blackmail, The Music Man (the ‘Marion the Librarian’ number), Attack of the Clones (looking remarkably like Resnais’s Bibliothèque nationale), The Breakfast Club (the library as prison), All the President’s Men and any Harry Potter film. Librarians themselves are often lazily caricatured – just think of the awful alternative fate envisaged for Donna Reed in It’s a Wonderful Life: unloved, plain and the town librarian, or the memorable rude librarians played by John Rothman in Sophie’s Choice and Judi Dench in Wetherby. Just occasionally a librarian gets portrayed sympathetically: Greer Garson in Adventure, Peter Sellers in Only Two Can Play, Tim Robbins in The Shawshank Redemption, and of course the favourite of many a librarian or archivist, Stephen Poliakoff’s TV series Shooting the Past, where the staff in a photographic library are the defenders of knowledge and humanity in the face of a soulless age.

The movies understand libraries, or at least know how to use them. But Resnais and Rivette understand something more. They understand that libraries are a part of what it is to be human. They collect our hopes and fears, and guide our discoveries. They represent the battle against the fragility of memory. They are the coming together of the prosaic and the magical, so that eventually one cannot tell the one from the other – Céline and Julie.

A version of this post is included in my book Let Me Dream Again: Essays on the Moving Image (Sticking Place Books, 2025)

Links:

- Martin Raish’s Librarians in the Movies hasn’t been updated since 2011 but it’s still a magnificent, ingenious resource – created by a librarian

- For libraries in the movies, as opposed to librarians, try Libraries and the Movies by Colin Higgins (guess what, a librarian)

- There’s an interview with Jacques Rivette from 1974 which covers his thinking behind the film, and much else besides at www.jacques-rivette.com

- And what do you know, today is national libraries day. A complete coincidence.

Hi Luke,

Do you know which magic book Julie’s reading? I’m searching everywhere for the title/ author and can’t find it! Thanks for this article, it was great.

Hi Olivia,

I didn’t know, but I’ve found it. It’s Traité méthodique de magie pratique by Dr. Papus, real name Gérard Encausse, first published in 1893. Information on him here: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/G%C3%A9rard_Encausse and on the book here: https://www.bookdepository.com/Elementary-Treatise-on-Practical-Magic-G%C3%A9rard-Encausse-Papus/9781947907010

Glad you like the article.

Luke

Wonderful! Thank you so much! How did you find it? I suppose she must have been holding an early edition (the red cover)?

Olivia

She holds up the book more or less so that the audience can read what is on the front. The worn cover makes ‘Magie’ clear, the word underneath it less so, but it ended in ‘ique’ so ‘pratique’ was a fair guess, and Google images did the rest. The edition with that cover is still available – see https://www.amazon.co.uk/Trait%C3%A9-m%C3%A9thodique-magie-pratique-Papus/dp/2703301057

Do you know where the library the appears in the film is (or was)? Or the magic club for that matter?

I’m sorry, I don’t know, but there must be some Rivette enthusiast out there who does.

Great subject and article, thanks. Another magical one is the Berlin State Library in Wim Wenders’ Wings of Desire. More Resnais (which may have influenced it) than Céline & Julie! It’s also covered here: https://reel-librarians.com/2018/01/31/angels-in-the-library-in-wings-of-desire/

Céline & Julie is mainly set in Montmartre. Julie’s workplace is upstairs so may be part of a larger library or school. Julie gives her taxi driver the real address of the magic club, or at least its exterior! BFI has a great webpage with some of the surprisingly linear locations: http://www.bfi.org.uk/features/celine-julie-go-boating-jacques-rivette-paris-locations

I was in Paris recently and visited the Céline et Julie Montmartre locations mentioned in that BFI article. I’d hoped to be able to track down the library, the magic club and the bandstand as well, but I didn’t have any luck with that. If anyone does know if they still exist and if so where they are I’d love to hear.

Celine is seen at the club outside drinking with her friends or coworkers early in the film, and later Julie tells the cab driver to take her to Rue Calvaire. The bar is still up there. As of January 2023, it is called Chez Plumeau, and in Montmartre it’s about halfway between the park and the funiculaire. The stairs were extremely busy when I saw it. I have no idea where the interiors were shot.

Excellent, thank you. We still need to find the library. It looks like a functioning library, though the children’s section could be a fantasy. I’ve scanned the scene for any clues and tried all the image databases I can think of, with no luck as yet. Anyone have a guide to 1970s Paris libraries?

Has anyone found Celine’s apartment? It had a tavern called Kronenbourg beneath it, and actually should be easier to find since the train tracks and overpass are visible nearby. On my last day in Paris, I had walked that way (toward those tracks, east of Montmartre) trying to locate the bandstand–I suspected that it was Paul Robin Square, since there was a green stand visible in the park on google maps like the one you can see in the film. Checking it out, I couldn’t confirm this however. There is now an indoor swimming pool by the park, and the surrounding buildings look different. My initial hunch was Square d’Anvers, but I did not get a chance to check that one out.

Thanks for that!