At last, after a year and a half at least, I got to see a day’s professional cricket. Having played some games for Members only, Kent County Cricket Club opened up its doors to ordinary folk such as myself. We had to book ahead, we were allocated seats, and the necessary constraints were a bit of a trial. The ground was split into north and south, with separate ground entrances, and no passing between one side to the other (so I looked wistfully at the unattainable tea room on the northern side, while those on that side looked with frustrated longing at the beer tent). We wore masks while wandering about the ground, but when seated removed them, the logic of which escaped me (the stands themselves were closed off, so we were in open ground). But we took to our seats, placed bags of sandwiches and tepid drinks to the side, settled ourselves comfortably, and let the game begin.

Day three of the county championship game between Kent and Northants, held at the St Lawrence Ground, Canterbury, was a particularly satisfying day’s cricket. The previous day’s play had been rained off, leaving the outfield damp enough that play did not start until after 1pm, but the sun caressed us, a few wispy white clouds offset a sharp blue sky, and all was idyllic. For the fans, it was heartening to see the Northants tailed promptly disposed off, our great favourite Darren Stevens once again claiming a five-wicket haul. Kent came into bat, responding to Northants’ first innings of 392. Wicketkeeper Ollie Robinson (not the same person as the England bowler), put into open the batting with the young Jordan Cox, gave a masterly demonstration of a controlled century. Joe Denly played elegant cover drives to warm the heart of any purist. We had a fine day of it.

How many are the ways in which one can enjoy a cricket match. To be there, live, is the primary experience, of course, though it comes in several forms. Firstly there is your location – things change according to your distance from the action and the angle at which you experience it, so a game see from the upper floor of a stand overlooking the bowler’s arms is different to one seated level with the action in boundary seating facing the wicket at right angles. The theatre has changed, and hence the understanding.

But also, depending on which version of the game you are watching, the contest can run over three or four days (five for a Test match), but not all have the time free or the money to see the entire game. So one sees part of the contest – that Saturday I saw most of the third day, but left with two hours still left for play – as though I were some aristocratic eighteenth-century theatregoer, arriving for the second act, leaving by the fourth, there to be seen, to get a flavour of things, then depart. One is aware that one is seeing only a part of the drama, some of which may have played out already, some of which which remains to be told. One does not need to know how things end, instead sampling what is passing. This is key to the greatness of cricket as story and theatre – it tells us more than we witness. There is a singular power that it grants to its observers, who in seeing the part sense the all.

This reconstructive quality becomes essential to the appreciation of cricket, since one seldom sees the whole game. The television highlights programme, such as the BBC has been providing for the current England-New Zealand Test series, exemplifies this, though it is hardly the finest expression of it. Boiling down a day’s play to a succession of notable incidents – wickets, boundaries, moments of controversy – it squeezes out those parts of the story that are not obviously sensational, but in so doing detracts from the game’s value as story. Specifically, it makes the viewer struggle to imagine anything other than that which is highlighted. There’s a ghost, the prince goes mad, there’s quite a bloodbath at the end. Hamlet is more than that.

For those with the time, money and the right subscription service, it is possible to see the entirety of a Test match on a TV screen. Streaming services now offer a myriad of options for following all or part of a game anywhere in the world, constrained only by service, camera placements and bandwidth. A few days after visiting Canterbury I was on the mid-Atlantic island of St Helena, or virtually so, struggling to watch Challengers play Sandy Bay Pirates in a T20 knockout final at St Helena’s dramatically-located ground on a high outcrop, surrounded by rocky hillsides, ocean in the distance. There were two camera positions I could choose from on the Cricheroes live service (a cricket app linked to live YouTube channel), giving distant views of the pitch at different ends, with the camera operator occasionally wandering off to show us the pavilion and scattered viewers. There was a wave of nostalgic feeling, since I was at that ground, three years ago, but the imagination had to work hard, as the picture broke up constantly and frequently froze altogether.

It is a pleasure to see cricket, whether live or screened, fully or partially, but the reality of the game exists in the mind. That’s why cricket works so well as radio broadcast – aided by skilled commentators attuned to the pictorial values of words. The sound is a trigger to the senses, reflective of more viewpoints than any any camera set-up might achieve. Tracing a game through social media, or via a mixed stream of text commentary, audience reaction and images, such as the BBC’s sport site so adroitly provides, relays the drama as a multi-faceted, collective experience, distilled through us, the solitary witness.

Reducing things still further, one can apprehend the same from the announcement of the scores alone. Such an announcement are given over the loudspeakers on a cricket ground during the intervals. Northants all out for 392; at the end of their innings Kent have boldly declared at 330-5, setting up what could be an exciting finish. No matter than in reality the game ended in a draw; at that point of announcement, one could imagine the whole theatre of it, the playing off of one side against the other, the strengths and the failings, the potential for dramatic resolution, the essence of all games in that one particular game.

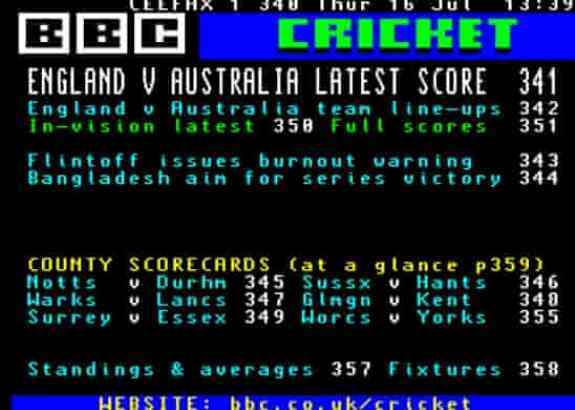

As a model example of how the mind makes the game, think back to the primitive days of information technology and the use of teletext on British television in the 1970s/80s (though it staggered on until the digital switchover of 2012). If one was not at the game, or did not have access to radio or TV (assuming the game was being broadcast at all), you could follow it live through the text-and-graphics service that came with the broadcast signal (Ceefax for BBC, Oracle for ITV). Having leafed slowly through the menu and found the three-figure number for cricket , you would wait an age for the match summary to appear, showing the latest score. And then you waited. And waited (from memory I think you had to refresh the screen by typing in the three-figure number again). The figure changed – a run had been scored. You waited again. The figure rose by four – a boundary. In the summary, and in the change of a number, you could see everything.

It was slower than real time, or felt that way. It felt absurdly laboured even then, but it was also thrilling in its way. You were faced always with the unknown, the necessary drama played out absolutely in the text before you. It provided basic information for those with time on their hands; in some strange way it eliminated time itself, or nearly so. It presented the sport as frozen yet moving at the same time. While yesterday’s newspaper report on a game shows you how the scores were by the end of the day, a record of time to that point, teletext gave you successions of moments. It was like a film run at the slowest speed possible, each frame motionless, the promise of the illusion of time implicit in the succession of data, yet what you were experiencing was actual time itself, whatever that might mean.

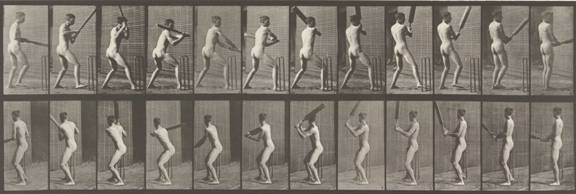

The earliest experimenters in the technologies that would eventually give us motion pictures – and so film, television, TV highlights packages and YouTube live streams – were driven by the desire to capture time, or in more practical terms to anatomise the mysteries of movement by capturing it piecemeal through sequence photography. Once sufficiently high-speed photography was possible, Eadweard Muybridge and especially the French physiologist Etienne-Jules Marey, began to photograph time. Such is the definition of the term applied to the method, chronophotography. In mechanical terms it worked: still images revealed the secrets of movement, most famously the galloping of a horse as unveiled by Muybridge. Time itself they did not capture, only the idea of it in the image of its passing.

Perhaps teletext supplied us with the purer expression of time and action. Freed from the distraction of the visual, it gave the idea and the idea only of time, frozen yet forever flowing, waiting for ball to reach bat with permutations to follow constrained only by the rules of the game. Our story-driven brains could reconstruct the rest.

Indeed, cricket must make philosophers of us all.

Links:

- On chronophotography, sport and the depiction of time, see my 2016 blog post, ‘Lost in an instant‘

- The Crichereroes app is available from Google Play and Apple’s App Store

- On the passionate enthusiasm with which cricket is played in St Helena, visit https://www.sthelenacricket.org

- For many screengrab images of teletext services, see the Teletext Museum