Among the ugliest of words to have been created to fit the digital age is ‘webinar’ (the ugliest of all is, of course, ‘blog’). It’s a word that highlights the parodic nature of so much of online life. In the real world we had seminars; in the world that imitates it, there are webinars.

That said, webinars are fascinating things. In these lockdown days, when we no longer gather together in rooms, there are all the more opportunities to meet, to discuss and to be lectured to through simulacra that are increasingly becoming the real thing, or to some degree indistinguishable from it. If I meet someone in reality to whom I have been speaking on Zoom, I don’t sense that much of a difference. We are our digital selves.

Last week I attended a webinar. It was held in Tulsa, Oklahoma, at 9am their time, which rather conveniently was 5pm my time. The event was entitled ‘Forever Young: Preserving The Archive of Bob Dylan’. In 2016 Bob Dylan’s archive was acquired by the George Kaiser Family Foundation, Kaiser being a billionaire Tulsa businessman and noted philanthropist. Kaiser reportedly has no great interest in Dylan, but combines local pride with a desire to promote education and social justice. The Foundation had previously purchased the archives of Oklahoman great, Woody Guthrie, creating the Woody Guthrie Center in Tulsa. Guthrie was an early hero of Dylan’s, and by some process of synergy Dylan’s people spoke to Kaiser’s people, and the Bob Dylan Archive was born.

There seem always to have been Dylan’s ‘people’ to present and preserve the phenomenon. Starting early with the team of manager Albert Grossman (who signed Dylan up in 1962, before the world knew anything of him). Dylan’s legacy has been created in tandem with the creation of the music. At first this manifested itself in the savvy licensing of the songs, the cornerstone of Dylan’s fortune. But as his career progressed everything was being kept. We know about all the masters of recording sessions, the alternative takes, the rejected songs, the rethought songs, thanks to the astonishing series of ‘Bootleg’ Dylan albums released over the past three decades: preserved, selected and released by those ‘people’ who were not only serving a generation of fans who wanted to more of the past as well as the present, but establishing the foundations of a long-lasting legacy.

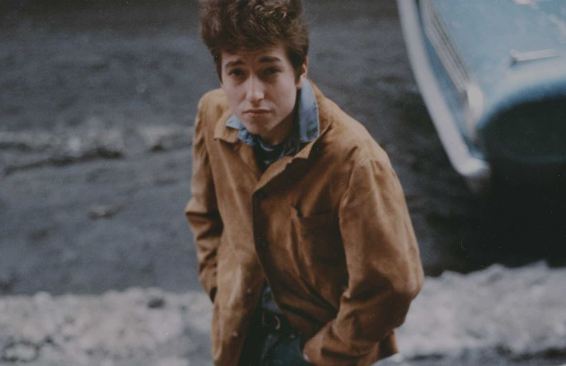

Promo video for the Bob Dylan Archive

Now we learn that not only was practically every recording kept, but so was the paperwork. The archive comprises some 100,000 items, housed at Tulsa University’s Helmerich Center for American Research at Gilcrease Museum. There are song master tapes, documentary films (plus music shorts and videos), session reports, notebooks, correspondence, contracts, sheet music, photographs, guitars, outfits, and song lyrics – handwritten drafts and amended typescripts, of songs known and unknown, revealing Dylan’s thought processes, or so the countless number of researcher hopefuls must be thinking who aim to study there.

It’s not going to be easy for them. Unsurprisingly there is huge demand for access which needs to be tightly managed. No A.J. Webermans need apply (to name the notorious collector of what was thrown out in Dylan’s garbage) – the archive’s website tell us sternly that “access to the archive will only be granted to individuals with qualified research projects, and only by appointment”. American, and indeed global, funding bodies can expect a slew of applications for PhD funding, giving would-be scholars sufficient clout to be able to book that plane to Tulsa.

For the rest of us, there will be a Bob Dylan Center in Tulsa, which will house the archive while providing a public museum front end, currently with assorted events leading up to its opening in 2021.

The webinar was one such event. It was as peculiar as it was engaging, as these things tend to be. The participants, each in different locations, attempted in their different ways to tackle the problem of how to address an audience that they could not see. Broadcasters are experts at this; archivists, much like the rest of us, less so. You could see the puzzlement in their eyes. There were the familiar awkward pauses when switching from speaker to presentation, the slow start before the speakers got into some kind of a groove, the asides to the unseen person managing the technology. All of these components can exist in real-life seminars and public lectures, but the closeness of the faces, the engaging absurdities of people’s home backgrounds (one speaker greeted us from his hotel bedroom, which felt a tad too intimate), create something that mocks as much as it serves its function.

The primary participants were Scott Goldman of the GRAMMY Museum (a polished convenor), Mark Davidson of the American Song Archives and archives director of the Bob Dylan Center (looking unfeasibly young and absolutely authoritative), Kelly Pribble of Iron Mountain Entertainment Services (speaking about the audio and video preservation challenges with awe-inspiring confidence) and the man with possibly the best job in the world, Michael Chaiken, curator of the Bob Dylan Archive. He gave the impression of someone bewildered by his luck yet entirely in control of his responsibilities.

It was an impressive quartet. We saw video promos, learned a bit about the history of the archive’s acquisition, and were given teasing hints about the gems they had discovered (excited talk about a hitherto lost song having been found). In the manner of these things, though they could not see their audience, the audience could send them questions via the Zoom chat function. These were surprisingly technical – there was more interest, apparently, in sample rates and lubricant loss of music tape than who might be included in Dylan’s correspondence. We learned that Dylan – who has no personal connection with Tulsa – had visited just the once, for an hour, but to see Woody Guthrie’s collection, not his own. There was expertise and authority on show, with a sense of absolute control.

I learned two things in particular from the webinar. The first was that a lot of money will buy you a great archive. That may seem obvious, but it ain’t necessarily so. Many ambitious endeavours have had large amounts of money thrown at them with dismal results, as we all know, but throw money at an archivist and they are likely to spend it well. Give them more and they will do an even better job. They can’t help themselves. Their mind is fixed on care combined with access, on the balance between immediate need and long-term goals. They are cautious and yet filled with belief. Maybe there are archives out there that show misuse of funds, but quite likely that’s only because someone forgot to consult the archivists. They are, by instinct and profession, a good long-term bet.

The second thing was the sense of fear. All archives are built on it. There is the fear of loss, but there is also the fear of irrelevance. Between the lines spoken by those people with such authority lurked a lingering worry about how posterity will view this legacy. Taste, and relevance, in popular music, tends to last a generation. The next generation must then reject it, because it is not theirs and because they lack experience of the circumstances that created it. In a profound sense it is no longer popular.

Dylan’s music has lasted across a number of generations because Dylan himself has lasted and is still creating music. He has always been more of an acquired taste than a wholly popular one, but over sixty years he has worked solely within popular forms (Dylan deciding to produce an oratorio is quite unthinkable). To be popular is to be a product of your times. You are responding to the moment.

But what when that moment has gone? Why will anyone want to listen to the songs of Bob Dylan decades from now, or indeed any of today’s popular song? It will be a niche taste. The relevance to the social and political issues of his time will engage some historians; his fame and influence will continue to attract biographers; some may consider the poetry of his lyrics; but what public meaning will he have? He may be forgotten, then rediscovered through some affinity with future concerns the like of which we cannot imagine, then slip into irrelevance again. The songs will continue to be sung, because so many were designed by Dylan to have the quality of folk music – that which must always touch the heart and so always be true. His song always will be sung. But why remember the composer?

It seems absurd, but why else do we build an archive except to plead with future times to understand us. This was what meant so much to us, that we built an archive to ensure the feeling lasted. Through this, you may remember us. We hope you will remember us.

We are like those four faces on the screen, looking out with both certainty and uncertainty, addressing an invisible audience who may not even be there at all.

Links:

- The Bob Dylan Archive site currently has only some explanatory texts, a couple of images, links to press notices, and contact information for academic and media enquiries

- The Bob Dylan Center site seems to have some web design issues, which doubtless will be resolved come 2021. There is information about levels of Membership that are on offer (for $7,500 you can “become a Founding Member with exclusive privileges, including lifetime membership and a commemorative edition of Heaven’s Door whiskey. Limited to 250 worldwide.” And an invite to the VIP Grand Opening)