So much of the past is now unreadable. Not just in a metaphysical sense, but quite literally so. Volume upon volume of the stuff that you cannot imagine anyone having had the stamina or the interest to attempt at the time. I pick up some works of the Victorian era and pity the typesetters. Time and sense must always move on.

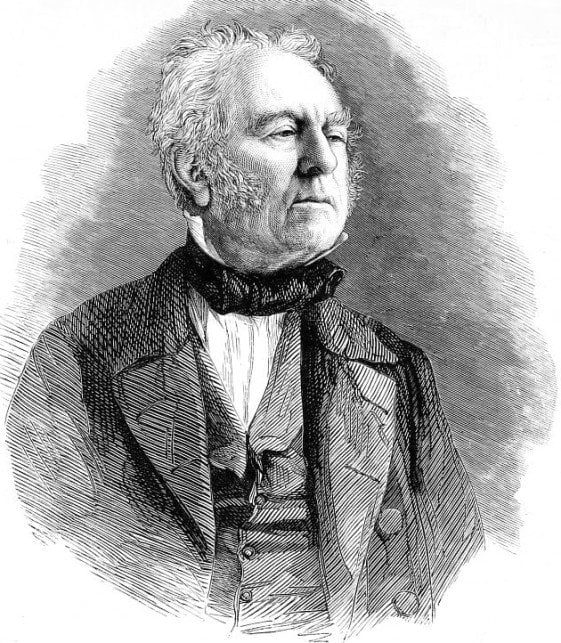

Take Walter Savage Landor (1775-1864), for example. Once a notable name, whose writings over a long life stretched from the Romantic era to high Victorianism. He made his name with a epic poem, in seven ‘books’ no less, Gebir. It’s a romance about a Spanish prince and his doomed love for an Egyptian queen. Written in a grand Miltonic style that was cherished at the time, its elevated tone now comes across as the antithesis of true feeling:

I sing the fates of Gebir! how he dwelt

Among those mountain-caverns, which retain

His labours yet, vash halls, and flowing wells,

Nor have forgotten their old masters…

Landor wrote copious long poetry in this manner, on classical and cod-classical themes. He wrote historical plays and dramatic scenes designed never to be performed, and a series of prose debates between notable figures from the past entitled Imaginary Conversations, once greatly admired for their wit and exquisite prose style, now only the preserve of the specialist. Landor is, most profoundly, out of print.

Yet Walter Savage Landor is one of my favourite poets. Not for Gebir, or his dramatic verse, but for that which he made a show of dismissing as trivia, but to which he returned again and again as the form in which he excelled – the short lyric, or epigram:

You ask how I, who could converse

With Pericles, can stoop to worse:

How I, who once had higher aims,

Can trifle so with epigrams.

I would not lose the wise from view,

But would amuse the children too;

Beside, my breath is short and weak,

And few must be the words I speak.

Landor was the kind of person who could have conversed with Pericles. His was a profoundly classical mind. His writings are sometimes satires of of the contemporary scene, but most of them caught up in the world of the ancients, in tone and subject matter. Children of his class were heavily schooled in the classics, in later life finding analogy, certainty and escape in this lost world of high feeling and noble endeavour.

Landor was, by all accounts, an extraordinarily difficult character, one who sought out conflict as a point of principle from his earliest years. His bad temper got him thrown out of Rugby school, then Oxford (he fired a gun at the windows of a Tory student whose politics the ardent republican Landor objected to), and eventually he left the country for Italy after offending his political enemies one time too many. He warred with everyone, usually unsuccessfully; naturally he married unhappily. He was nevertheless loved by his literary friends, chief among them Charles Dickens, who gently caricatured him as Boythorn in Bleak House and named one of his sons after him. But Landor never wrote a less true line than in his most famous work, ‘Dying Speech of an Old Philosopher’, where he claimed he ‘strove with none’. Landor strove with everyone.

I strove with none, for none was worth my strife:

Nature I loved, and, next to Nature, Art:

I warm’d both hands before the fire of Life;

It sinks; and I am ready to depart.

It might be argued that Landor is setting down the thoughts of a character, but everyone in Landor’s writings speaks with Landor’s voice. The poem nevertheless has been much anthologised because it speaks for anyone reviewing the end of a life. It is the quintessential Landor epigram. An epigram, originally an inscription on a tomb that evolved as poetry into a witty observation, still carries with it – at least in Landor’s hands – that sense of a summation of a life, bound up with life’s ironies. It says that, for all our endeavours, we may all end up with four lines at most, admitting that he strove, but that life has had the last laugh.

Landor was the master of the epigram and the short lyric, because he knew its classical practitioners well (Martial, Horace, Sappho), because he felt at one with them (he often composed in Latin first, to get his ideas in order), and because he was acutely attuned to the irony. The Oxford Companion to Classical Literature says of the best epigrams that they “combine intensity of feeling with great simplicity of expression”, a phase that neatly describes Landor’s finest efforts. Here is ‘Dirce’, perhaps my favourite four lines in all English poetry:

Stand close around, ye Stygian set,

With Dirce in one board conveyed!

Or Charon, seeing, may forget

That he is old and she a shade.

Dirce, in classical mythology, was an obscure figure known chiefly for being killed when tied to the horns of a bull, but not for her beauty. Landor appears to have picked her name solely for its euphony (der-chay). The deceased Dirce is being ferried across the river Styx (hence ‘Stygian set’) to the underworld. Charon is the ferryman. There’s a dark threat of sexual assault, thwarted by the realities of age and death, that gives ‘Dirce’ its peculiar resonance. Life, in every sense, is over, summed up by the exquisite balance of that final line. Landor always married the telling word to sound. Note the subtle assonance of ‘board’ and ‘conveyed’ (to have used ‘boat’ would have been wrong), the two-foot ringing echo of ‘Charon’ and ‘seeing’, and the same falling finality to ‘old’ and ‘shade’. It is a poem where every word seems counterbalanced with another, a fine-carved, multi-faceted jewel that captures a moment, a drama that never happens, a snapshot of lost time.

Many of Landor’s short poems are epigrammatic in style rather than specifically epigrams, in the sense of comments found on tombs that sum up a life. But the suggestion behind the original epigrams was to give the effect of the dead person addressing the passer-by. That passer-by recognises them for a brief while, and in so doing recognises something in themselves. Landor’s poems that revive classic voices work in this vein. The Greek poet Sappho was not an epigrammist, but the fragments of her poetry have the function of a few surviving words escaped from the past to remind us that here once was a life, and feeling. Landor’s adaptation of Sappho’s most celebrated short verse is sublime:

Mother, I cannot mind my wheel;

My fingers ache, my lips are dry:

Oh! if you felt the pain I feel!

But Oh, who ever felt as I?No longer could I doubt him true;

All other men may use deceit:

He always said my eyes were blue,

And often swore my lips were sweet.

A Landor epigram catches a moment’s thought. Some of the weaker ones – of which there are many – read like ideas dashed down the moment they popped up in the poet’s head, whereas the effective epigram is contemplative: a moment in time, yet boundless too:

My hopes retire; my wishes as before

Struggle to find their resting-place in vain:

The ebbing sea thus beats against the shore;

The shore repels it; it returns again.

Inevitably death, ageing and loss are recurring themes. A short lyric rather than a true epigram, ‘The leaves are falling’ frames the mournfulness at autumn turning in the winter of life with the same astute counterbalancing of words, sounds and rhythms as characterises ‘Dirce’ – ‘Joyous/unjoyous’ and ‘spring/summer’, ‘moisture’ and ‘fire’, and at the end of each stanza a molossus, or three long syllables, a characteristic of Greek and Latin poetry:

The leaves are falling; so am I;

The few late flowers have moisture in the eye;

So have I too.

Scarcely on any bough is heard

Joyous, or even unjoyous, bird

the whole wood through.Winter may come: he brings but nigher

His circle (yearly narrowing) to the fire

Where old friends meet:

Let him; now heaven is overcast,

And spring and summer both are past,

And all things sweet.

In ‘March 24’ Landor writes so movingly on the death of his sister Elizabeth, a poem that shows the uses of nature as both real and metaphoric that places Landor among the Romantics (“Nature I loved, and, next to Nature, Art”):

Sharp crocus wakes the froward year;

In their old haunts birds reappear;

From yonder elm, yet black with rain,

The cushat looks deep down for grain

Thrown on the gravel-walk; here comes

The redbreast to the sill for crumbs.

Fly off! fly off! I can not wait

To welcome ye, as she of late.

The earliest of my friends is gone.

Alas! almost my only one!

The few as dear, long wafted o’er,

Await me on a sunnier shore.

Landor’s short love poems, alongside those dwelling on loss, are what kept him in the poetry anthologies of more romantic times past. Many a Victorian heart beat a little faster on reading the ecstatic ‘Rose Aylmer’ (“Ah what avails the sceptred race, Ah what the form divine! What every virtue, every grace! Rose Aylmer, all were thine”). Disappointed in love as he was by everything else in life, Landor addressed many poems to ‘Ianthe’, in reality Sophia Jane Swift, who was engaged to another. Landor wrote some of this most touching and lyrical poetry to Ianthe, still composing poems to her in old age:

‘Do you remember me? or are you proud?’

Lightly advancing thro’ her star-trimm’d crowd,

Ianthe said, and lookt into my eyes,

‘A yes, a yes, to both: for Memory

Where you but once have been must ever be,

And at your voice Pride from his throne must rise’

Landor’s short poems are too sentimental in appearance to make the anthologies now. The Penguin Book of Romantic Verse grants him three entries only: an extract from Gebir, and two poems of moderate length, ‘To Wordsworth’ and the resigned and finely classical ‘Hegemon to Praxinoe’ (“Is there any season, O my soul, When the sources of bitter tears dry up, And the uprooted flowers take their places again Along the torrent bed?”). But his best short poems have an extra quality that makes them worthy of commemorating.

In part it is the technical mastery of language in concentrated form. Landor has control over words in precise contradiction to the control he never had over life. Unsettled as he was in temperament, his short poetry is profoundly composed (the longer works not always so). He places the right word in the right place, the peculiar word, though often only after a struggle:

How many verses have I thrown

Into the fire because the one

Peculiar word, the wanted most,

Was irrevocably lost.

But more than language and form, there is something frozen about the short poems: they are like statues, or the figures caught in action on Ancient Greek pottery. There is an absence of feeling as much as there is a welling up of feeling. Who cares for Dirce? Landor captures the classical form, and its irony. There is no life in a statue. The figures around the vase have the form of action but do not move. Those words on an inscription will not revive the one who is lost. Landor’s poems live in the past, yet know the past is something that that they cannot recover. It is a poetry of ruins and tombstones.

Life hurries by, and who can stay

One winged Hour upon her way?

The broken trellis then restore

And train the woodbine round the door.

This is the fifth in an occasional series of posts on favourite poets of mine

Links:

- There is no book of Landor’s poetry in print. Poems by Walter Savage Landor, edited by Geoffrey Grigson and published in 1964, is the volume to seek out.

- There is a good summary of Landor’s life and works, with several examples of his poetry, on the Poetry Foundation site

Can’t say I share your enthusiasm for Landor. But you make a good case, and focusing on the epigrams certainly makes him more attractive. Makes me wonder about Walter Scott, once vastly popular and officially celebrated in Scotland (lines of his all around Waverley Station, named after his novel). But does anyone read his poetry today as poetry? Maybe in need of the kind of advocacy you perform for Landor?

With Landor it’s a case of looking for the few glittering treasures among mountains of stone. But I like them when I find them.

Scott’s poetry is probably better on railway stations than on the printed page. It does nothing for me (the little that I know of it), save for ‘Proud Maisie’, which has the economy and the chill of the traditional ballads it imitates.