Bob Dylan is the man for a global crisis. His album Love and Theft was unwittingly released on 11 September 2001, a cornerstone of culture at a time when the world seemed to be tumbling. Now, in the middle of the coronavirus pandemic that has see a quarter of the world’s population retreat behind its doors, Dylan has published on his website, with a ‘stay safe’ message to us all, his first new song in eight years, ‘Murder Most Foul‘. At a shade under 17 minutes long, it is the longest song he has ever produced. It feels already like one of his finest. It is absolutely a song for our times.

Murder Most Foul

‘Murder Most Foul’ takes as its ostensible theme the assassination of President John F. Kennedy in 1963. It begins in media res, reminiscent of his song ‘Hurricane‘ in being a ballad in which the narrative’s crisis point is delivered up front, the task of singer and song then being to deal with the consequences:

It was a dark day in Dallas, November ’63

A day that will live on in infamy

President Kennedy was a-ridin’ high

Good day to be livin’ and a good day to die

Being led to the slaughter like a sacrificial lamb

He said, “Wait a minute, boys, you know who I am?”

“Of course we do, we know who you are!”

Then they blew off his head while he was still in the car

But this is no ballad, nor a simple recounting of the Kennedy assassination and its aftermath. The song moves into mysterious territory, interweaving elements of Kennedy’s fate – sometimes told in the third person, sometimes first, as though Dylan were speaking for him – with a journey through a changed world:

I’m riding in a long, black Lincoln limousine

Ridin’ in the backseat next to my wife

Headed straight on in to the afterlife

I’m leaning to the left, I got my head in her lap

Hold on, I’ve been led into some kind of a trap

Where we ask no quarter, and no quarter do we give

We’re right down the street, from the street where you live

They mutilated his body and they took out his brain

What more could they do? They piled on the pain

But his soul was not there where it was supposed to be at

For the last fifty years they’ve been searchin’ for that

Freedom, oh freedom, freedom over me

I hate to tell you, mister, but only dead men are free

The song transforms into a litany of cultural references, drawn down from Dylan’s memory, with a strong emphasis on film and song. Some of these are what one might call solid choices – The Beatles, Charlie Parker, John Lee Hooker, Buster Keaton, Marilyn Monroe, Thelonius Monk – but others cause surprise. Dylan references The Eagles, The Who’s rock opera Tommy, Queen’s ‘Another One Bites the Dust’, A Nightmare on Elm Street, Billy Joel, Lindsey Buckingham and Stevie Nicks, and William Shakespeare (The Merchant of Venice and Lady Macbeth get a mention, and of course the song’s title comes from Hamlet).

These are no arbitrary choices caused by a bout of nostalgia. We can judge that simply by who or what is not mentioned: no Woody Guthrie, Dave Van Ronk, Joan Baez, Johnny Cash, the Band or others who played an important part in Dylan’s musical life. The purpose is not personal but rather a lesson in the mad cornucopia of sounds, sights and personalities that occupy our minds and can guide our thoughts. These are things our minds might call up at any moment, because they resonate. It’s about the sheer randomness of collective memory.

The figure Dylan employs to tie all this together is 1960s American disc jockey Wolfman Jack:

What’s new, pussycat? What’d I say?

I said the soul of a nation been torn away

And it’s beginning to go into a slow decay

And that it’s thirty-six hours past Judgment Day

Wolfman Jack, he’s speaking in tongues

He’s going on and on at the top of his lungs

Play me a song, Mr. Wolfman Jack

Play it for me in my long Cadillac

Play me that “Only the Good Die Young”

Take me to the place Tom Dooley was hung

Play “St. James Infirmary” and the Court of King James

If you want to remember, you better write down the names

Dylan calls upon Wolfman Jack to play us the music that might make sense of a world gone wrong (one of the song’s most startling lines says of the time following the assassination “The age of the Antichrist has just only begun”). The song, in its last two verses (of five) turns into playlist. It is a list of requests from Dylan, or from us, which could be requests to a radio DJ but applies just as well to world that finds its soundtrack through iTunes or Spotify. It is a playlist, and a prayer, for Dylan presents Kennedy as a Christ-like figure, making Wolfman Jack maybe an evangelist, or a David with his harp, singing psalms of lamentation and praise. Some of the last lines of the song include what could a knowing reference to the harp, or harmonica, of Little Walter, often referred to as the ‘king’ of blues harpists, or else another great harmonica player Sonny Terry (‘Key to the Highway’ was a signature song of Terry and guitarist-singer Brownie McGhee):

Play “Misty” for me and “That Old Devil Moon”

Play “Anything Goes” and “Memphis in June”

Play “Lonely At the Top” and “Lonely Are the Brave”

Play it for Houdini spinning around his grave

Play Jelly Roll Morton, play “Lucille”

Play “Deep In a Dream”, and play “Driving Wheel”

Play “Moonlight Sonata” in F-sharp

And “A Key to the Highway” for the king on the harp

We should not forget that Dylan was DJ once himself, playing music of which Wolfman Jack would undoubtedly have approved, on Theme Time Radio Hour, which ran 2006-2009.

‘Murder Most Foul’ has so many reference points. This is not just in what the lyrics point to, but in Dylan’s musical past. It is unclear when the song was written or recorded. Dylan says simply on his website that “This is an unreleased song we recorded a while back that you might find interesting”. It is a recent recording, because Dylan’s singing voice is clear and mellow, as we have become accustomed to in his last few albums of cover versions (he’s given up smoking, and with it has gone the ragged gargle that so challenged some listeners). The accompaniment is simple: piano, violin and brushed percussion, in keeping with the jazz leanings of his recent music. Yet it also sounds like nothing else that Dylan has recorded – or anyone else. It is almost tuneless, almost monotone, a recitation over drone-like music that is more lullaby than the tirade the lyrics on their own might suggest. It may be the most avant garde piece of music that Dylan has yet produced.

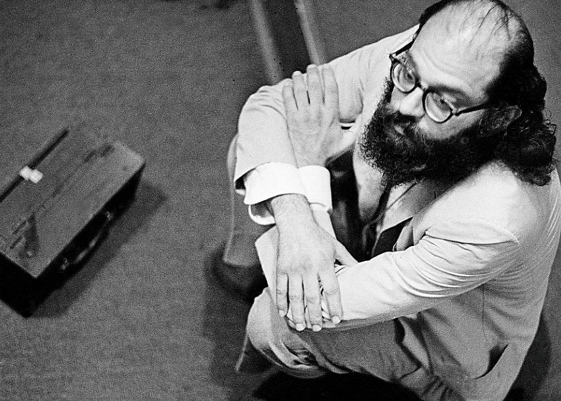

One reference point is the poet Allen Ginsberg, a good friend of Dylan’s and a great influence on his writing, who would often include a harmonium to accompany his poetry readings. There is certainly a mantra-like quality to ‘Murder Most Foul’ that Ginsberg would have recognised. Though definitely not any influence on Dylan, I hear similarities to the rambling tales with the simplest of harmonium accompaniment employed by the Scottish poet and humorist Ivor Cutler (check out Cutler delivering the finale to Robert Wyatt’s ‘Little Red Robin Hood Hits the Road‘, from his album Rock Bottom, in particular).

There are affinities with the songs of ruin and retribution on Dylan’s last album of original songs, Tempest, in particular the long title track. ‘Tempest‘ uses the sinking of the Titanic (both the history and the 1997 film) to turn disaster into the metaphysical. But there is also a connection with the album’s final song, ‘Roll on John‘, a tribute to another fallen icon, John Lennon, that uses the language of sacrifice (“Sailing through the trade winds bound for the South / Rags on your back just like any other slave / They tied your hands and they clamped your mouth / Wasn’t no way out of that deep, dark cave”). ‘Roll on John’ is afflicted by too much sentimentality and some weak punning language (“Down in the quarry with the Quarrymen”). ‘Murder Most Foul’ follows its example but turns its mistakes into virtues.

I see other reference points. The discursive narrative echoes the Ginsberg-inspired, rambling poetry of Dylan’s early years, particularly those texts that appeared on the sleeve notes of some of his albums, texts that when young I would scour religiously for meaning. Here, for example, from 1964’s Another Side of Bob Dylan:

boards block up all there is t’ see.

eviction. infection gangrene an’

atom bombs. both ends exist only

because there is someone who wants

profit. boy loses eyesight. becomes

airplane pilot. people pound their

chests an’ other people’s chests an’

interpret bibles t’ suit their own

means. respect is just a misinterpreted word

an’ if Jesus Christ himself came

down through these streets, Christianity

would start all over again. standin’

on the stage of all ground. insects

play in their own world. snakes

slide through the weeds. ants come an’

go through the grass. turtles an’ lizards

make their way through the sand. everything

crawls. everything …

an’ everything still crawls

There is also a strong link with a type of song that usually shows Dylan at his weakest. Periodically throughout his musical career, and particularly during the 1980s, Dylan has written lyrics which are essentially lists. There is a single idea to the song, which is expressed through a succession of examples until the point where he runs out of ideas, or rhymes. Early examples include ‘Rainy Day Women # 12 & 35’, ‘Sad-eyed Lady of the Lowlands’ (sort of), and ‘Father of Night’. From 1979, at the start of his born-again Christian phase, they came in unwelcome profusion: ‘Gotta Serve Somebody’, ‘Shot of Love’, ‘Union Sundown’, ‘Trust Yourself’, ‘Everything is Broken’, ‘Wiggle Wiggle’ and ‘God Knows’. All, save ‘Everything is Broken’, are songwriting low points, where too often Dylan had run out of ideas yet felt he had to write something:

Broken hands on broken ploughs

Broken treaties, broken vows

Broken pipes, broken tools

People bending broken rules

Hound dog howling, bullfrog croaking

Everything is broken

‘Murder Most Foul’ is a list song – not for two-thirds of its running time, but absolutely so thereafter. It pours out line after line listing songs, performers or films that occur to the artist, each introduced by the word ‘Play’. But this is not the absence of an idea, but the continual enrichment of it. Each citation, each invocation to ‘play’, deepens the mystery, builds up a picture whose parameters we cannot ever grasp, because each new line pushes back the boundaries.

This then links to the song’s religious incantation element. There is something of Allen Ginsberg repeating his Hari Krishna-inspired chants, but the psalms of David and the Hebrew tradition feel like the closer analogy. I wrote a while ago about the British 18th-century poet Christopher Smart, who was inspired by Hebrew antiphonal verse in his long poem ‘Jubilate Agno’, with lines beginning with the word ‘Let’ answered by lines starting with the word ‘For’.

Let Hushim rejoice with the King’s Fisher, who is of royal beauty, tho’ plebeian size

For in my nature I quested for beauty, but God, God hath sent me to sea for pearls

Smart also wrote a long poem, ‘A Song of David’, which is a work of praise to God but also to the biblical figure and supposed psalm-writer David, in whom Smart closely identified. Likewise ‘Murder Most Foul’ blurs the boundaries between Christ and Kennedy, with Dylan as the eulogist who identifies with his subject. I doubt that Dylan knows anything of Christopher Smart, but were he to investigate his poetry, he might recognise a fellow spirit.

Play “Mystery Train” for Mr. Mystery

The man who fell down dead like a rootless tree

Play it for the reverend, play it for the pastor

Play it for the dog that got no master

Play Oscar Peterson, play Stan Getz

Play “Blue Sky,” play Dickey Betts

Play Art Pepper, Thelonious Monk

Charlie Parker and all that junk

All that junk and “All That Jazz”

Play something for the Birdman of Alcatraz

Play Buster Keaton, play Harold Lloyd

Play Bugsy Siegel, play Pretty Boy Floyd

Play the numbers, play the odds

Play “Cry Me a River” for the Lord of the gods

Every virus serves as metaphor. It’s the sickness under which we live made manifest. Dylan wrote ‘Murder Most Foul’ probably long before the present coronavirus pandemic, but its release at this time cannot be coincidental. It’s the biological expression of a world gone wrong Dylan identified in his 1993 album of that name. Its title track, adapted from 1930s group The Mississippi Sheiks’ ‘The World is Going Wrong‘, is a song Dylan describes in his powerful liner notes as being “against cultural policy”.

World Gone Wrong – which I hold to be Dylan’s finest album – established the theme for much of the outstanding music he has produced over the last two decades. He sees “the soul of a nation been torn away / And it’s beginning to go into a slow decay / And … it’s thirty-six hours past Judgment Day”. It is a process of decay that Dylan, we now learn, dates back to John Kennedy’s assassination, which was not so far off from when he started out as a professional singer. That Dylan finds any hope beyond our political world is because of the songs on his, and everybody’s, playlist. It is in the remembering of them that we may find order again.

Play darkness and death will come when it comes

Play “Love Me Or Leave Me” by the great Bud Powell

Play “The Blood-stained Banner”, play “Murder Most Foul”

Links:

- ‘Murder Most Foul’ is available on YouTube (embedded above) or on various platforms, links to which are provided by the bobdylan.com website

- The lyrics to ‘Murder Most Foul’ are given on genius.com

- Update (14/4/20) – the lyrics are now available on bobdylan.com

- The already lengthy debates about the song’s genesis and import can be tracked through the excellent Dylanology site Expecting Rain

- Someone is bound to make a Spotify list out of the song’s ‘play’ requests. I’ll add the link here when they do… and it happened on the day of the song’s release with this list on NPR: https://www.npr.org/sections/allsongs/2020/03/27/822468820/a-list-of-the-songs-named-in-bob-dylans-murder-most-foul – which, naturally, has a Spotify playlist to go with it. Indeed there are already a dozen or more Spotify playlists giving the songs Dylan refers to – each of them different

A great review and analysis. Like many people, I have been stunned by this song – because of its content – I have been a student of the assassination, and I like Bob Dylan as what I would call a casual fan (I have seen him live once in I think the 1980s).

For the songwriters on this thread, I am interested in one particular aspect of this song – the point of view(s). In 2013, I took an “Intro to Songwriting” course by Pat Pattison on Coursera https://www.patpattison.com/. Pat teaches: “Who is speaking? To whom? What messages are they conveying?” As best I can tell, Dylan uses these speakers: The Narrator (Dylan?), JFK, Killers, LHO, Nellie Connally, The American People. I am not completely sure who is speaking for each line, but tried to take a shot at it. I would love for others thoughts on this. Thanks for this review.

Dylan has subsequently released two more songs online, ‘I Count Multitudes’ and ‘False Prophet’. A new album (double-CD), Rough and Rowdy Ways, is set for release on June 19.