I grew up among rocks. My parents lived in Tunbridge Wells, and while for some the town might suggest only crusty generals and snobbery over the tea cups, for others Tunbridge Wells has meant climbing and adventure. The surrounding countryside is blessed with sandstone outcrops, whose evocative names still resonate for me with a powerful nostalgia: Bowles Rocks, Eridge Green Rocks, Bulls Hollow Rocks, High Rocks, Wellington Rocks, Harrison’s Rocks. Above all, Harrison’s Rocks.

It was to these outcrops that a generation of post-war climbers came to test out their skills – climbing on such outcrops is often known as ‘bouldering’ – often before adventuring further on mountains where the real climbing was to be done. Tunbridge Wells was an easy drive or train journey down from London, from which came a steady stream of weekend climbers looking to scale the twenty or thirty-foot rocks that offered an ideal exercise in the essentials of the sport.

We were lucky – we lived locally, and my father was one of the young men for whom this was their adventure playground. One came armed with boots, ropes, carabiners, a rucsack, rough clothes, a flask of tea and – essentially – a flannel kept damp by being sealed in a plastic bag. The sand otherwise got everywhere. After a day’s good climbing, all then repaired to Terry’s Festerhaunt in nearby Groombridge, run by the king and queen of Harrison’s, Terry and Julie Tullis, for mugs of tea and shared tales of how each had defied gravity.

You also had your pocket-book guide that mapped the territory. Each rock offered several climbing routes, each evocatively named and scored according to its degree of difficulty:

1A Easy and Moderate

1B Moderately Difficult

2A Difficult, easy

2B Difficult, hard

3A Very difficult, easy

3B Very difficult, hard

4A Severe, easy

4B Severe, hard

5A Very Severe, easy

5B Very Severe, medium

5C Very Severe, hard

6A Extremely Severe

To this day, I cannot go past a rockface, or even the side of a building that is anything more than just a plain wall, without giving it a quick assessment as a climbing possibility. Hmm, looks like a 5B to me, until you get to that ledge, then the rest is easy. And I still wonder, as my young self did back then, what sort of a climb would merit being scored a 6B. Sheer glass, perhaps?

The guide most had was E.C. Pyatt’s South-East England, first published in 1956, as the climbing boom was reaching its peak. For millennia the rocks had only been rocks, ignored by humans once cave habitation no longer sufficed. It was not until little more than a century ago that the rock outcrops around Tunbridge Wells were discovered by anyone with an interest in climbing. Probably no one actually climbed there until the mid-1920s. The first to do so seems to have been Nea Barnard, later Morin, who had climbed similar rocks at Fontainbleau before discovering Harrison’s Rocks were on her doorstep (she was a Tunbridge Wells native). She pioneered several routes before they had names, later joined by her husband Jean Morin, and then some of the great mid-century mountaineering enthusiasts, among them Eric Shipton, Johnnie Lees and Menlove Edwards.

With those first climbs came the names. By the time of Pyatt’s book, at least as my 1969 edition has it, every route came with a number, rating, guidance on approach, and names that were among my first taste of poetry, as with these climbs at Harrison’s (‘N.L. means ‘not led’, i.e. not climbed by anyone without a supporting rope):

14 – Unclimbed Wall (5B). A fine wall.

32 – Musical Crack (6A, N.L.). This is climbed direct and is very strenuous.

58 – Edward’s Effort (5C). uses the obvious crack a few feet right of the Isolated Buttress Climb.

83 – The Niblock (5C). An excellent route.

99 – Moonlight Arête (5A). The deterioration of small pocket holds is increasing the difficulty of the direct start.

129 – Giant’s Ear (5A). An obvious ear-shaped flake in the centre of the face.

138 – Stupid Effort (5A). Take the left-hand start to Long Crack but go straight up the overhangs above, keeping out of the crack all the way

182 – Weeping Slab (5A). Steep and wet.

I was too young for anything except the easy scrambling routes (Isometric Chimney, 1A; Snout Crack, 2A), but I knew every route by name, scampering along the base of rocks while my father scaled another 5C. I returned as a teenager, never getting beyond a 5A (Long Layback, of happy memory). Then time and circumstance intervened, and the rock climbing habit fell away. But if anyone would ask me what my favourite places were, Harrison’s Rocks were always near the top of the list, though more and more years went by since I had ever visited them. The other weekend, on a damp autumn Sunday, I did so once again.

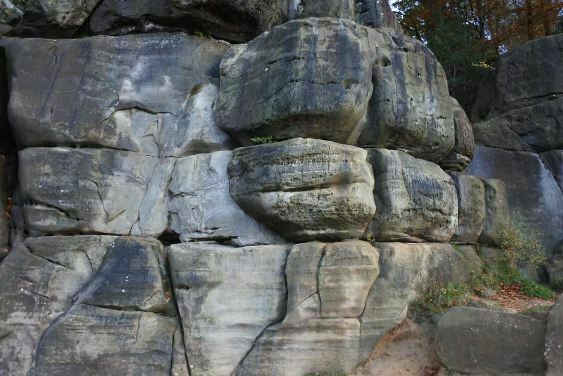

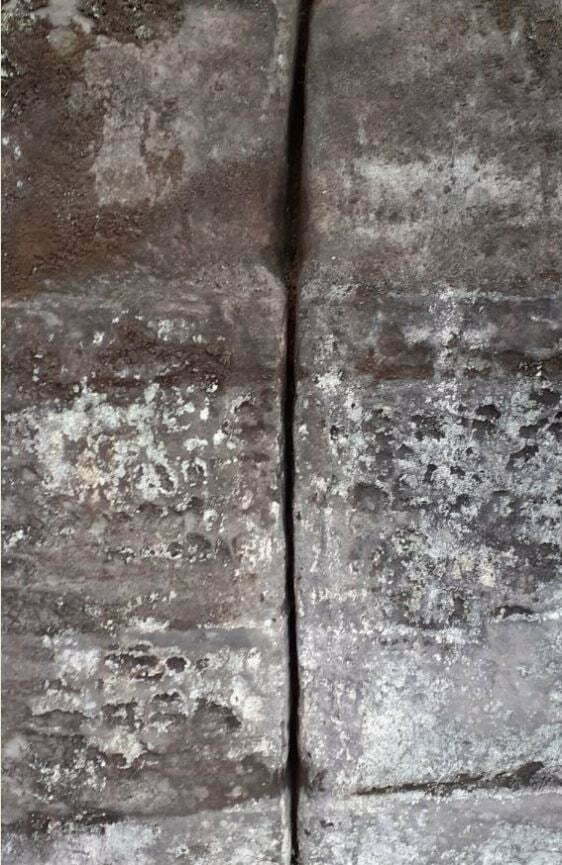

What is it about sandstone rock outcrops that is so beautiful? It’s not just the former attraction of climbing, or some nostalgic trigger of happy memories. Wind and water erosion have shaped the rock masses into rounded, pitted surfaces, marked with cracks, crevices and indentations, ideal for the climber. The gritty stone itself is both hard and yielding, inviting the hand to grip, the foot to make a first step up, and so for the ascent to begin. There is a peculiar relationship between human and rock, the latter shaping itself to the needs, to the imagination of the former.

Even if one is not a climber, or cannot imagine that climbing could be a pleasure, one is still in a sculpture gallery. The horizontal layers of sedimentary rock intersect with the vertical cracks and chimneys that divide up the rock, setting out rich, rough patterns to bewitch the attentive eye. The rocks appear to be organic forms, things which grew up out of the ground alongside the trees and plants, shaped as only nature knows how to shape. It is no wonder that they have inspired such imaginative, playful names – just of themselves they are such a powerful stimulus to the imagination.

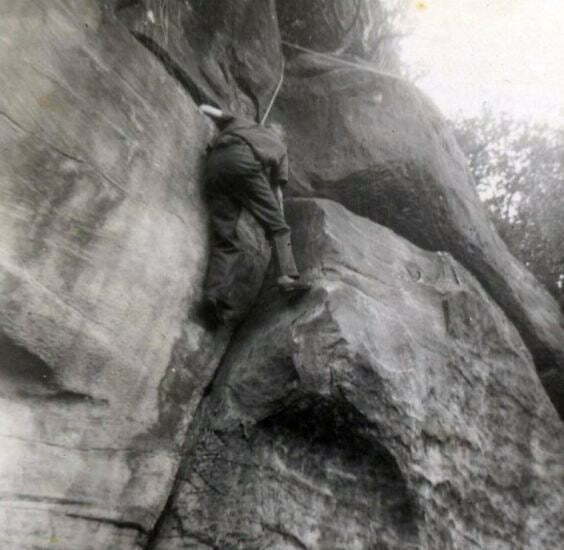

The rock becomes something else once a climber is part of the picture. The scene changes from something eternal, carved through millennia by wind and rain, to something emblematic of human ambition, even triumph. It is not just physical agility that is on show, but mental agility too. We see the climber halfway up the rockface, mastering a particular manoeuvre, reaching up to the next ledge, calculating through a mixture of strategy and tactics. The climber has looked up, assessed the route, decided upon a course of action, but only when face to face with the rock do holds appear, or are revealed to be far less sure than hoped. Obstacles loom large, and actions unfold through a situation that is always balanced between control and crisis.

Then there is the fear. Every climber could fall (rope notwithstanding). To climb is to fly; it is contesting gravity. Any climber will know of the peculiar sensation one gets when you find yourself in a difficult position and the body tries to fight against this mad impulse to ascend. Samuel Taylor Coleridge, who among his many other achievements was arguably the first rock climber (in the sense of someone who climbed for pleasure rather than necessity), wrote of this sensation in an 1802 letter, describing a descent from the top of Scafell in the Lake District:

The next three drops were not … a foot more than my height – But every drop increased the palsy of my Limbs – I shook all over … and now I had only two more to drop down – to return was impossible – but of these the first was tremendous, it was twice my own height, & the Ledge at the bottom was [so] exceedingly narrow, that if I dropt down upon it I must of necessity have fallen backwards & of course killed myself. My limbs were all in a tremble – I lay upon my back to rest myself, & was beginning according to my Custom to laugh at myself for a Madman.

Coleridge recorded not simply the act of climbing (or descending afterwards), but its effect on the spirit. The fear was thrilling, the mental conquering of what the body fought against a triumph. And even if we do not climb ourselves, the sight of the climber on the face of the rock tells us something profound about ourselves. We can fall at any time, and only we can save ourselves from falling.

It was a muddy trudge through woodland from the car park to the northern end of Harrison’s Rocks. The rock themselves were grey-green with damp. There were few people around on this Sunday afternoon, despite the moderately fine weather – a clutch of climbers around the ever-popular Bow Window (4A), another at the southern end trying out Rift (5B) and Zig-Zag Wall (5A). So much of it I remembered, that I could almost have traversed the landscape blindfold – the bulges and the crevices, the handholds and footholds, the routes that still lay stored in the mind, in readiness despite all the passing years – the very contours of memory.

In my head I must be always climbing, rising above the trembling, knowing that somehow there will be a way upwards.

Links:

- There is a guide to Harrison’s Rocks on the site of the British Mountaineering Council, which manages the rocks

- There is an article on Nea Morin by Jeff Connor on UK Climbing, ‘Nea Morin – Hard Days for a Lady‘

- Coleridge’s pioneering activities as a climber and fellwalker are described in Keir Davidson’s fine book O Joy for me!: Samuel Taylor Coleridge and the Origins of Fellwaking in the Lake District 1790-1802

Lovely piece, much appreciated by someone who climbed there and knew the names also. Thank you

Thank you. The names always made the place that extra bit special for me.