The 2019 cricket World Cup got underway with something extraordinary. Occasionally one is able to look beyond the noisy crowds, the pop music blaring out at every pause, the multi-coloured kits, the banalities of the TV commentary and the formulaic highlights programmes, to moments when the sport shines through. So it was that in the opening game Ben Stokes, England’s have-a-go all-rounder, took an astonishing dismissal of South African batsman Andile Phehlukwayo. Standing near the boundary at deep midwicket, Stokes found himself out of position for what would normally have been a regulation outfield catch. With the ball sailing rapidly above and beyond him, Stokes had to jump backwards and side-on, reaching out his right hand to the ball in hope as he careened backwards. He grasped the ball, somehow managing to hold on to it as he fell. The look of astonishment on those in the crowd nearby was matched by Stokes’ own amazed expression. It was, in every sense, super human.

The television coverage replayed the catch from all the angles available, at slow speed so you could appreciate the artistry and sheer bravado of it, and in real time to convince you of the impossibility of the coup. The joy on everyone’s faces (beyond those of the South Africans) was not at the capture of a wicket, but at the excellence all had witnessed. Sport lives for such pinnacles. And that is what the catch, any catch, is all about.

It is said that every great sport event has many more thousands who claim to have been there than could possibly have been the case – a mixture of wish-fulfilment and confusion between actual and televised memories. I have never witnessed a great sporting event. Pretty much every sporting contest where I have been in the crowd was ordinary. Somebody won, someone may have got a medal, but the sport itself was ordinary. I have seen only early rounds, contests that fizzled out into draws, games that were of some partisan interest and no more – just sport as part of the daily routine, reassuring but unexceptional.

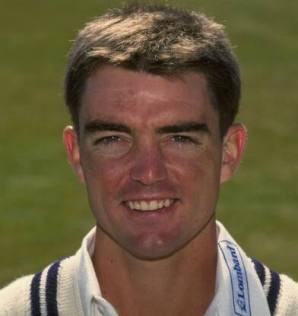

There is one exception, and it was a catch. It was during a Kent v Leicestershire cricket match, on the third day of a four-day county championship game, 18 July 1997. I had taken a week’s holiday to enable me to see the full game, which took place at the St Lawrence ground, Canterbury. Much of game was conducted under grey skies, with a little drizzle at times, heavy rain on the afternoon of the second day, but that only added to the special feeling of the occasion. This was the serious business of cricket, and I cherished each stage and every ritual, the whole unfolding of the drama over four days. Kent had been on good form, recently topping the County Championship,and it was a team that I cherished. Oh my Walker and my Marsh (and Patel, McCague, Ealham, Fleming, Headley, Igglesden, Key, Llong) of long ago…

The ball came hurtling towards Strang. He was in a better position than Stokes, but that much closer to the batsman and so with almost no time to think. In the split second available, he leapt backwards and to his side. Though memory has now faded and I cannot remember which hand took the ball, I remember the emotion. The catch was unbelievable. It defied probability while simultaneously confirming your belief in in the excellence of the sport that you followed. I was seated in an upper-floor stand, the Annexe (it is now the Underwood and Knott Stand), positioned almost directly behind the wicket, so had the perfect view. Few others can have been seated in the small stand (there were around 500 people watching around the ground as a whole); all I can remember is that behind a glass partition where scorers and press would sit, there was one man who was a fellow astonished witness. We looked at each other, in amazement, wordlessly agreeing that we had never seen anything like that. It had shaken us to the core.

Those were different times. The match was not televised, there were no smart phones, no means to capture the extraordinary from the multiple angles enjoyed by Stokes’s triumph. I have not been able to find any photograph. Wisden’s Cricketer’s Almanack and the Kent Country Cricket Club annual for 1998 do not mention the catch, while the couple of newspaper accounts that I have traced refer merely to Wells having been ‘brilliantly caught‘ by Strang. Were it not in my head, the catch might disappear entirely.

Nostalgia makes me exaggerate. I vaguely recall that the journalists in the Annexe had monitors which presumably had some video feed of the game, and an official photographer would certainly have captured something. But I can find nothing, so nothing is what we have. Nostalgia has likewise undoubtedly elevated the quality of the catch in my memory. It was brilliant, but was it extraordinary? I remember it so. All memory is fiction, shaping not what we saw but rather what we need to recall. To my mind it has become the best of what I have seen on a sporting field. Something must be best, after all, and only memory can decide.

There is something about the catch which elevates cricket as a sport. Though many sports with a ball incorporate catching, it is rare for a catch to affect the scoring or the fate of the players. Baseball comes nearest, but although it is a part of the romance of the game and had its own sensational catch recently, it does not match cricket for the fundamental part the catch plays in the significance of the game. Catching in cricket is a reflection of the game’s range and profundity. There are catches in the deep, close catches (the fielder, wearing a helmet, placed close to the batter as much to intimidate as to catch the ball), wicket-keeper catches with thick gloves, slip catches (where a ring of fielders lines up beside the wicket-keeper when the ball is new and fast and an unsteady batsman may nick the ball behind them), one-handed athletic catches, fumbled catches, catches where one person loses the ball but second makes the catch before the ball hits the ground, sky-high catches, low catches, the happy coup of caught-and-bowled, the deep shame of the dropped catch, the deeper shame of the false catch claimed. Such a rich array, yet it seems it has generated no literature of its own. That is very strange, when the catch forms so central a part in how cricket is understood and valued.

For there is more than athletics or aesthetics to the catch. ‘Catch’ is one of those old English words with a remarkable number of definitions. The noun ‘catch’ can be the grasping of a ball, a clasp, a desirable mate, a concealed difficulty, or a kind of vocal music; the verb can be the act of catching a ball, to capture something, to contract an illness, to take fire, to imitate, to trap, to be in time for, to strike. It’s a diverse set of meanings, though connected by concepts of capture and surprise. The catch in cricket is an interruption to the flow. It represents the triumph of human intervention over the inevitability of things. Through our wit, our physical prowess or our intellectual agility, we can pluck hope out of the sky, turning inevitability into delightful uncertainty, reversing fortune. The catch is a challenge to the continuum. The catch is a triumph over time itself.

But at the same time the catch reveals time’s triumph over us. Every catch implies a death. The catch is a guillotine, cutting out a life in full flow. Every batter will know that the next ball could be their last, the outcome of which lies only partly within their control. Such is the morality of cricket. There is something atavistic about the catch succeeding where it prevents a ball from touching the ground. It’s an echo of ancient times when games developed out of religious rituals, their symbolic functions designed to propitiate the gods. We hit the ball in the hope of it returning to earth, completing a cycle. The catch reminds us instead that we are mortal, cutting us off from hope and certainty.

We all have our innings, with our chance to build a score, but if we do not fall by any other means, we will be felled by a catch. There are other ways of getting out in a cricket match – bowled, leg before wicket, run out, hit wicket – but it is the catch that is so exhilarating: for its execution across time and space, for what it reveals of the rewards and punishments that govern life as they govern sport, for its exceptionalism. All of the desperate razzamatazz that characterises the modern game, with its music, colour, hype and hysteria, cannot hide cricket’s profound metaphorical resonance. Among all sports, it offers the greatest riches for the mind. The catch proves this.