Was this face the face

That every day under his household roof

Did keep ten thousand men? Was this the face

That like the sun did make beholders wink? …

A brittle glory shineth in this face.

As brittle as the glory is the face.

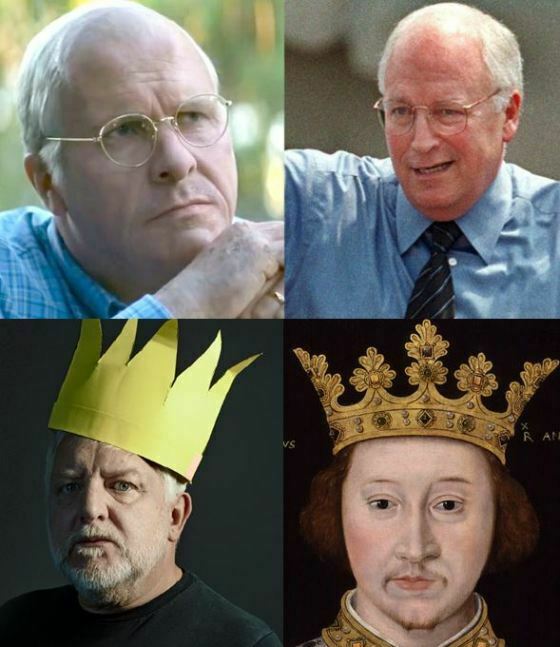

To the cinema, and the next day to the theatre, so see productions which I had not thought would be so closely aligned, yet it seems so. One was the feature film Vice, a biopic exposé of US vice-president Dick Cheney. The other was about another Richard, Shakespeare’s The Tragedy of King Richard the Second, playing at the Almeida Theatre. Both are studies of the assumption of power, and the faces of power.

I was looking forward to seeing Vice, having greatly admired director Adam McKay’s earlier film The Big Short, on the financial crisis of 2008. Vice similarly takes on recent history, in a deconstructed, mocking style that McKay has made his own. Sadly I found the film to be quite poor, even dull. It tried too hard, had a narrator reeling out selective facts from an Idiot’s Guide to American politics, and gave us a diatribe when what we wanted was understanding. We know what Dick Cheney did (or some of it), we know he was a dark character operating in dark times, but why? From where did that thirst for power come, and why did Cheney pursue it in the way that he did? Consequences are not the same as answers.

There is a lot about the film that is fun, with the director breaking down the illusion of reality on repeated occasions, including end credits in the middle of the film when it might have been that Cheney’s life would carry on in quiet retirement breeding prize-winning golden retrievers, a Fox News commentator who comments on herself, a focus group that ends up telling us its thoughts about the film we have just seen (and then gets into a fight over it), and Cheney turning to the cinema audience and saying what else was there to do given the threats that the nation faced after 9/11. That’s the only point where we see just something of what drove the man, and it is not enough.

One of the gags in Vice has Cheney and his wife turning to cod-Shakespearean dialogue at the height of their political machinations. The joke is that you don’t get people in dramas telling us their thoughts as events unfold about them as you do in a Shakespeare play, but the film might have been that much better if the Shakespearean conceit had been extended. Richard II is a model example of how speech can serve both an exterior and an interior purpose, showing how characters explain themselves to themselves (and us) while becoming ever more trapped by circumstances, as their story progresses. Action is thought; thought is action.

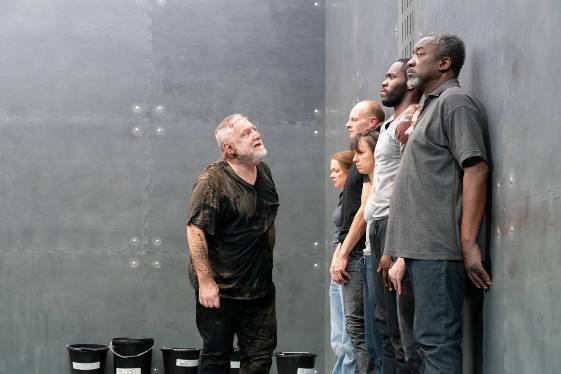

The Almeida’s production of The Tragedy of King Richard the Second (to give its full title) is quite an experience. Directed by Joe Hill-Gibbins (as much as iconoclast in his field as McKay), and starring Simon Russell Beale as the king, it is a rapid (100mins), frenetic roller-coaster interpretation of the play. Much is cut or re-ordered, a cast of just eight stay the entire time on a grey metal box of a set, the only added colour being blood that is thrown about liberally from buckets placed on the stage. It is so choreographed to be more like a dance piece than conventional theatre, while the single set robs the play of its variety and hence some of its sense.

As ever, Shakespeare comes to the rescue. Richard II, one of the most beautifully written plays in the English language, is a profound study of the nature of power. It shows power as a quality of mind. The fall of Richard and the rise of Bolingbroke, who succeeds him as Henry IV, is to a degree a matter of geographical and military manouverings. But (aided by the utter anonymity of the set) what we witness is a battle of minds, as Richard loses power the more he thinks upon it, doubts that Bolingbroke inherits in his turn (the production ends with a bitter, dry laugh from Bolingbroke at his supposed moment of triumph). Power is only power where you believe you are in power. You can no longer be a king once you question your own kingship.

What must the King do now? Must he submit?

The King shall do it. Must he be deposed?

The King shall be contented. Must he lose

The name of King? A God’s name, let it go.

What Richard loses, Cheney seizes. Vice makes much of the unitary executive theory of US politics (essentially all power resides ultimately in the one person), suggesting to us that Cheney turned disappointment at coming bottom of a poll of potential presidential candidates to seeking ultimate power by stealth. He converts the meaningless role of vice president into a platform for the exercise of true power, simply by force of will and the unwitting connivance of a weak president (George Bush), whom Cheney keeps in the air during 9/11 while he makes the key decisions. This coup culminates in the decision to invade Iraq, because that’s what the focus groups find easiest to understand, and the move will make Cheney’s company Halliburton very rich.

This is cartoon history. Simon Jenkins, in a recent article for The Guardian, ‘Fake-history films like Vice and The Uncivil War are the new threat to truth‘, says that the falsities and misleading simplicities of historical films are a dangerous misrepresentation of history. ‘If a newspaper declared on its front page, “These stories are based on real events, and some of them are true”, it would be laughed out of court. When films do it, they claims Oscars’. The argument is well made, though the answer is not to demand that history films keep strictly to factual truth but rather to educate audiences to understand better the complexities involved. Filmmakers have a duty to story, not history. The problem with Vice is that it asserts the latter, and in so doing fails to succeed with the former.

How much better might Vice have been if it had focussed more on George Bush than Dick Cheney. The story of the man unsuited to high office but driven there by the demands of his family, only to find power slipping from his hands through the machinations of another who has the greater understanding of (and desire for) power – now there is a subject worthy of a Shakespeare play. Richard II may not provide the perfect analogy, but its theme of the transfer of kingship is grounded in the idea of the divine right of kings, the unitary executive theory of its time. Where does the right to power lie? Should they who understand best how power works be those who end up exercising it?

There was something else that I saw in the two productions, and it lay in the faces. Among the pleasures that Vice offers is its lookalike performances – Christian Bale as Cheney, Steve Carrell as Donald Rumsfeld, Sam Rockwell as George Bush, with cameos along the way for Henry Kissinger, Condoleeza Rice, Gerald Ford, Colin Powell, Karl Rove and many more. It is not just the snapshot recognition, but in some way power (for that is what it must be) that is transferred to the audience through the act of viewing. To be impersonated is to be captured, to suffer some loss of power. It is why we value cartoons, but there is something more in seeing how an actor can inhabit greatness and so reveal that which is less than great. They become a key to our understanding, just as many a celebrity or politician has become that which an impersonator uses to portray them. We are only ever what people think we are.

It may have been the same when Richard II was first staged. One of the challenges modern audiences have with Shakespeare’s history plays is all those dukes named after places. Which is Northumberland and why is he arguing with Carlisle? What is Gloucester to York, or Surrey to Salisbury? Their motives and allegiances may all be there in Holinshed, faithfully transferred to the stage by Shakespeare, but they seem almost interchangeable. It must have been different in 1595. Though the figures were not contemporaries – it was far too dangerous for the Elizabethan stage to depict living characters – they would have been far better understood, as relatively recent history. Moreover, the audience must have seen parallels with those who did have power over them. Those named after those same places still ruled the land, yet here they were on the stage before us, the victim of forces the same as the rest of us. They became the actors who portrayed them.

Famously, supporters of the Earl of Essex, who planned a revolt against Queen Elizabeth in 1601, sponsored a performance of Richard II (presumed to be Shakespeare’s version), because of the political resonances. “I am Richard II, know ye not that?” Elizabeth is supposed to have said. It’s unlikely, but if it makes for bad history it makes for a good story. Richard II was a mirror for its troubled times.

We see our world reflected on our stages and screens. In doing so we gain some understanding, and through that some satisfaction. They order that which for us had been disordered. That’s why adherence to factual truth should not be the governing factor behind history films, but understanding must. Vice fails because it does not explore its own certainties. Richard II is the very antithesis of certainty, a model for any deep study of power and the mind that must wield it.

But whate’er I be,

Nor I, nor any man but that man is,

With nothing shall be pleased till be he eased

With being nothing.

Another in that long list of movies that are not as good as a Shakespeare play 🙂 I think you are being way too harsh on VICE as I suspect a lot ofwhat is in it would surprise many viewers (it shouldn’t but there’s the problem, right?) – and anyway, what are the better American films from the last few years that look at similar subjects? Not Oliver Stone’s W … But some very fine thoughts here Luke and certainly have to agree with you on what the best bits of the film are (like the mid-story end credits) and yes, truly, Cheney is just too unknowable even by the end. The play sounds great though/ While in Oz I saw an open air production of the concluding half of their productions of WARS OF THE ROSES derived from HENRY VI and RICHARD III – it employed three actors for Richard at different stages of his life, which worked superbly. Here’s their website: http://www.sportforjove.com.au/theatre-play/rose-riot-the-wars-of-the-roses

Vice is a remarkable film, almost agitprop, bold in ambition and execution, and an amazing thing to have come out of (fairly) mainstream American cinema. It’s just that I found it obvious, and therefore boring. I’ll see it again when the dust has settled, and hopefully will view it more kindly. But it’s not Shakespeare, when it could have been (a little bit).

The Wars of the Roses productions sound rather good – I particularly like the idea of the three Richards. I’ve long had a particular fondness for the Henry Vis since seeing Helen Mirren and Alan Howard at the RSC, late 70s, all three in one day at the Aldwych. Quite sensational, even seismic. I believe my future employer may have been one of the stagehands…

MJW in his sub rosa Aldwych days? Sounds very plausible 🙂 Don’t think I saw anything there until 1987 at the earliest, but used to go there a lot in my undergrad days of course, finances permitting, it being a stone’s throw from LSE.

Watching Vice again, it does have a little more to recommend it. The anger, at least, is clearer to me now. But it’s still comic book stuff that shies away from deep reasoning. It’s Richard III, not Richard II.