In all of the long and notable histories of the UK’s national film archive and its national sound archive only one person – to the best of my knowledge – has worked for both institutions. Me. This is not through any great archival ability stretching across the two media. My contributions to film archiving have been more nebulous than practical, while I am now based in the British Library Sound Archive not for any expertise in sound (I have none) but because the Library wanted a moving image curator, and they had to sit me somewhere – so among the Sound Archive is where I sat, and still sit.

A sound map of the British Library Sound Archive, recorded by John Kannenberg

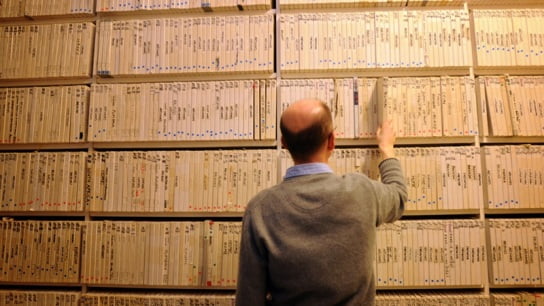

And although I still wear that moving image hat for the Library, and have recently taken on a news curatorial brief as well, I get involved in the world of sound, particularly radio. Just recently I’ve been helping to manage the early stages of a large-scale programme called Save our Sounds. This is an ambitious undertaking, which essentially is setting out to preserve the nation’s sound heritage, and which is driven by the generally recognised assumption that we have fifteen years in which to preserve the sound archives we have (through digitisation), before either the media themselves deteriorate of the means to play them become unavailable. The reason for acting is that these threats will only get worse and mean that the cost of saving sounds will get all the more expensive as the years go by. So we have to start preserving now.

One of the last Black Country chainmakers, Lucy Woodall, sings the worksong ‘Chainmaker lad is a masher’ and talks about singing

At the same time there need to be systems in place for the capture of future sounds, and the other half of Save our Sounds is looking at direct ingest of sounds from publishers (primarily music publishers) and greatly extending the archiving of radio. Around 92% of the current output of the UK 700 or so licensed radio stations is not properly archived (if it is kept at all), a shameful situation. We’ve worked out how much all of this will cost, and it comes to around £40m, money which as things stand we have not got.

So, nothing like a challenge.

Nightingale song, recorded in Kent, 2008

It’s a good time to be getting more interested in sounds, from the rise of services such as Spotify, SoundCloud and BBC Playlister, to BBC Four’s recent fine series The Sound of Song, presented by Neil Brand, which gives us the history of how technology has determined the production and distribution of recorded song, and encourages all of us to listen that much more attentively to the sounds about us. The British Library has recognised the special case for sounds, and made their preservation one of the leading themes of its 2015-2023 strategy Living Knowledge (awful name, but good thinking behind it). There is definitely something in the air.

One of the earliest recordings of chamber music, recorded in 1905

All of which is making me think what it is that is so special about sound archives. Why keep sounds? Whom do they serve? How do they function? What purpose do they serve when so many sounds are now freely or cheaply available wherever we are? How do they differ from other kinds of archives (such as film)? Why pay £40m on their preservation? Why do they matter?

Sounds matter because they resonate. Listening to them puts us in a particular place that is both the time and space in which they were recorded and that timeless space that exists within our heads. They do not distract, in the way that visual media inevitably do (that is, visual media show us the object to be looked at, but our eyes tend to wander to see things sometimes differently to the matter ostensibly in hand). To listen therefore is to concentrate.

Sounds move us, because we recognise that they are speaking to us, that a communication has been made. Sounds help us locate who we are and where we are. Sounds help to identify boundaries, yet at the same time to transcend them. A voice or a melody may belong to a particular culture and be part of the society that it helps define, yet equally such sounds may move anyone, may belong to anyone.

Sounds contain memories, associations, echoes and refractions. They transmit information which cannot be written down (musical scores notwithstanding). Sounds make us think, and in rationalising what we hear we gain extra understanding. Sounds help explain the world, while creating worlds of their own. Sounds encourage wonder, and enquiry.

Sounds are everywhere, and yet evanescent. We live in a world seemingly saturated with voice, songs, sounds natural and mechanical, yet they are lost if not recorded, and are perilously reliant for their survival on the media that contain them and the organisations in whose current interest it is that those media are kept. A recorded sound, and all that we can associate with it through listening to it, can be so easily snuffed out. A wiped tape is a tragedy.

A sound archive is a beautiful idea. It is a civilised idea. Its absence would be mere oblivion.

Gull in a gale

Links:

- The Save our Sounds page has information on the programme and the British Library Sound Archive

- Over 50,000 sound recordings from the Sound Archive can be listened to at http://sounds.bl.uk

- As a first step in the programme we are conducting a survey of the UK’s sound collection, whether in public or private hands, with the same of creating a UK Sound Directory. The survey runs until the end of March 2015.