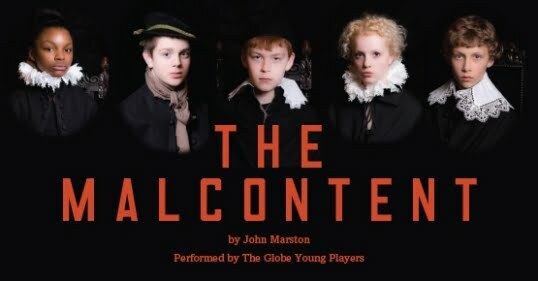

John Marston’s play The Malcontent (c.1603) is currently being performed at the Sam Wanamaker Playhouse (part of the Globe Theatre complex) in London. As was the case in the 1600s, the play is being performed by children in an indoor theatre. Marston’s play was first acted at the Blackfriars theatre by the Children of the Chapel Royal. The boys’ company began performing plays at Blackfriars in 19602 and such performances became very popular. In Hamlet, Shakespeare has Rosencrantz complain of such productions:

Nay, their endeavour keeps in the wonted pace: but there is, sir, an aery of children, little eyases, that cry out on the top of question, and are most tyrannically clapped for’t: these are now the fashion …

Marston wrote most of his plays for boys’ companies, yet his plays must have come across peculiarly through young mouths, being as they are often satirical in tone and scathing about human kind in general. Marston himself was a misanthropic, cynical character, habitually at war with society. His personality seems to have been expressed through the play’s title figure, Malevole, the malcontent. Malevole is a duke named Altofront who has been deposed by his brother. He disguises himself as a hanger-on to regain his dukedom and in the process expresses his disgust at the life of the court. A complicated plot sees Pietro turn remorseful over his behaviour and join forces with Malevole to turn the tables on upstart courtier Mendoza, the villain of the piece.

The malcontent is a staple figure of late Elizabethan and Jacobean drama. The world-weary cynic who tries to stand outside the ugliness of the world, while expressing his contempt for it, but gets sucked into it eventually (often to enact some revenge) is there in Malevole, in Shakespeare’s Hamlet and Jacques (As You Like It), in Vindice (The Revenger’s Tragedy, by Cyril Tourneur or Thomas Middleton, depending on who you consult), in George Chapman’s eponymous Bussy d’Ambois, and in John Webster’s Flamineo (The White Devil) and Bosola (The Duchess of Malfi). Such discontented social commentators seem to be plausible guises for the playwrights themselves: outsiders with privileged insight, disguising their disgust at the world’s ways to try and protect themselves from that world’s vengefulness, yet forced to speak, and ultimately (like Hamlet and Malevole, who bears a some resemblance to Shakespeare’s character – written a few years earlier) to act.

The malcontent is not quite the same as the numerous Machiavellian characters that populate Jacobean drama (of which The Malcontent‘s Mendoza is one), though the two sometimes overlap, and both are symptomatic of the disquiet and malaise prevalent in Jacobean times. Una Ellis-Fermor writes of the “sense of defeat” characteristic of the times following the death of Elizabeth and the accession of James, in The Jacobean Drama:

This mood, culminating as it did in and about the year 1605, took the form for public and private men of a sense of impending fate, of a state of affairs so unstable that great or sustained effort was suspended for a time and a sense of the futility of man’s achievement set in.

I don’t know whether the comparison has been made before, but another malcontent figure is Edmund Blackadder. One of the reasons the television series Blackadder II, set in Elizabethan England, works so well is that Blackadder is such a recognisably Elizabethan/Jacobean character. He is the cynical outsider, familiar with the court yet standing outside it, who sees human ambition and desires for what they are. That sense of impending fate hangs over him, making him a creature of his times (and ours), even if strictly speaking he is Elizabethan, not Jacobean. Blackadder is not driven by a thirst for revenge, nor does he have a residual belief in a goodness from which humankind has turned away, as Malevole does, but his outsider status seems very much the kind that Webster, Shakespeare and Marston created, maybe as alter egos. Consider these words from The Malcontent, spoken by Malevole, and imagine them being uttered by Edmund Blackadder:

Think this: this earth is the only grave and Golgotha wherein all things that live must rot: ’tis but the draught wherein the heavenly bodies discharge their corruption, the very muckhill on which the sublunary orbs cast their excrement: man is the slime of this dung-pit, and princes are the governors of these men: for, for our souls, they are as free as emperors, all of one piece: there goes but on pair of shears betwixt an emperor and the son of a bagpiper: only the dyeing, dressing, pressing, glossing, makes the difference.

Such savage indignation suits a skilled adult performer such as Rowan Atkinson. The effect when spoken by a boy actor (Joseph Marshall) is rather odd. The production at the Sam Wanamaker Theatre – the new Globe space that recreates indoors theatres of the period such as Blackfriars, down to the wooden construction, candle lighting, and hard narrow seats – is performed by children between twelve and sixteen. They are talented, they have learned their words well, and perform with such passion and conviction as they may, but one loses all sense of moral indignation and inner horror. They capture the humour in the play very well (particularly Sam Hird, in drag, as the sluttish Maquerelle), but cannot reflect anger at a world they do not as yet fully know.

It’s an odd experiment, recreating how the play would have originally been seen, when we are not the original audience. It certainly persuades you that the past is a foreign country when you realise just how many of the plays in the early seventeenth century were seen like this, performed by children (all boys then, but mixed now). What was the appeal? How did audiences react? Some of the present-day audience reaction may give a guide. We laughed at times at children uttering words whose import lay outside their experience; we laughed at other times at how piquantly Marston’s bitter phrases came across when spoken by teenagers. Perhaps the contemporary audience was similarly amused, though one feels they would have been more attuned to the words and their import, and hence more stirred by the savagery within.

There was a charm about the production, but do not expect such child performances to become a vogue. We can see how things would have looked in a Jacobean theatre, but it does not brings us any nearer to the Jacobeans. One of the best-known television comedies of our times does that far better. John Marston would have recognised something of his creation, and himself, in Edmund Blackadder.

One thought on “The malcontent”