For my talent is to give an impression upon words by punching, that when the reader casts his eye upon ’em, he takes up the image from the mould which I have made.

Christopher Smart

One of my favourite Kent walks is through the Fairlawne estate; those parts of it that are public, that is. If you go to Tonbridge and proceed two miles north along the main road, a side-turning on the left down Horns Lodge Lane takes you with startling suddenness away from urban anonymity to rural idyll. Rolling fields, gracefully composed lines of trees along the skyline, and patches of delightful woodland through which the path weaves to the curves of the land. Horses forage in the distance, and if you sit still and are patient, the occasional deer may come close, look at you quizzically, then run away startled at your first escape of breath. Not a soul is to be seen, usually. The only indications of what controls this regimented paradise are a few signs warning you away from the private sections of the estate, and far off amid some trees Fairlawne house itself, owned by racehorse breeder Prince Khalid Abdullah, first cousin of King Abdullah of Saudi Arabia.

Fairlawne was where the poet Christopher Smart, to whom I have long been devoted, spent his childhood. Smart was born in 1722 at Fairlawne (the reference sources say Shipbourne, which is the name of the nearby village), when the house belonged to William, Viscount Vane and Smart’s father Peter was its steward. He was a bright child, first taught by his father (the son of a headmaster), then schooled in Maidstone. From the age of eleven he was encouraged by the Vane family when he moved to Durham after his father’s death, spending much time at the family seat of Raby Castle.

Smart’s aristocratic support in Durham enabled him to become an outstanding classics scholar, leading to Cambridge (Pembroke Hall) and some glittering early successes as a classicist and poet. But he never forgot his Kent childhood, and to some degree never wanted to escape it. Being one who found the trials of adulthood particularly hard, in his heart he remained a child, and in stature too – one sad poem of his is entitled ‘The Author Apologizes to a Lady for His Being a Little Man’ (“Yes, contumelious fair, you scorn / The amorous dwarf that courts you to his arms”). His poem in praise of the Kent of his memories, The Hop-Garden, composed in the Georgic style, rhapsodises over the landscape of his formative years:

Next Shipbourne, tho’ her precincts are confin’d

To narrow limits, yet can show a train

Of village beauties, pastorally sweet,

And rurally magnificent. Here Fairlawn

Opes her delightful prospects; dear Fairlawn

There, where at once variance and agreed,

Nature and art hold dalliance.

It was while Smart was still at Cambridge that the clouds started to gather. He gained a reputation for indebtedness and eccentric behaviour, with Thomas Gray writing prophetically of Smart at this time, that “All this … must come to a Jayl, or Bedlam, and that without any help, almost without pity”.

Smart moved to London to pursue the uncertain career of a Grub Street journalist, writing anything and everything to feed the newspapers and periodicals of the time. He suffered bouts of ill health combined with chronic alcoholism, gradually succumbing to a form of religious mania, notoriously expressed in his need to fall to his knees in public in prayer and urging those around his to join him. Samuel Johnson, we are told, viewed such activity with kindness, wryly declaring that “I’d as life pray with Kit Smart as anyone else”, elsewhere arguing:

Madness frequently discovers itself by an unnecessary deviation from the usual modes of the world. My poor friend Smart shewed the disturbance of his mind, by falling upon his knees, and saying his prayers in the street, or in any other unusual place. Now, although, rationally speaking, it is a greater madness not to pray at all, than to pray as Smart did, I am afraid there are so many who do not pray, that their understanding is not called in question.

Smart reveals the anguish behind his mental infirmity in the heartfelt Hymn to the Supreme Being on Recovery from a Dangerous Fit of Illness:

But, O immortals! – What had I to plead

When Death stood o’er me with his threat’ning lance,

When reason left me in the time of need,

And sense was lost in terror or in trance?

My sinking soul was with my blood inflamed,

And the celestial image sunk, defaced and maim’d.

The year in which Smart published that poem, 1756, he was committed to St Luke’s Hospital for Lunatics, then to a Mr. Potter’s asylum of Bethnal Green. It is unclear just how ‘mad’ Smart actually was – he was committed to St Luke’s by his publisher John Newbury, who had many reasons for being annoyed by Smart, and 18th-century views of madness were wide-ranging and vague – but he remained committed for seven years. On leaving the asylum in 1763 he found himself separated from wife (he was married to Newbury’s daughter) and children, clearly his improvident behaviour having made him intolerable. He returned to writing, but also to drink, and was imprisoned for indebtedness. He died in 1771.

The standard sources say that Christopher Smart produced two outstanding pieces of writing, and the standard sources are right. Although there has been much critical activity in recent years which has looked sympathetically at Smart’s voluminous poetic output, the greater part of it religious in theme, all of it demonstrating considerable technical skill, only on two occasions did Smart produce works that astonish rather than earn the admiration of the diligent specialist. Both were produced in Bedlam, as it were.

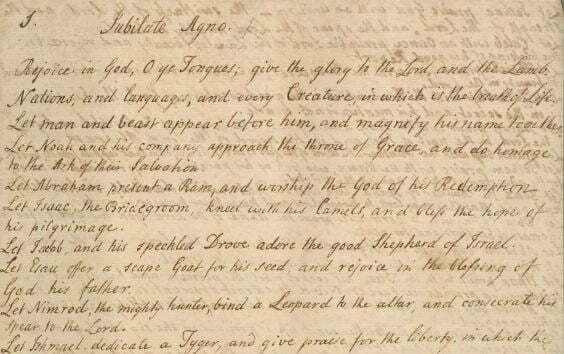

Jubilate Agno was written while Smart was confined in the asylum, between 1759 and 1763. It remained in manuscript form, unpublished until 1939, when editor W.F. Stead produced Rejoice in the Lamb: A Song from Bedlam to an astonished literary world. In 1950 a second editor, W.H. Bond, demonstrated how the underlying structure operated, revealing a work not of bizarre chaos albeit with extraordinary poetic invention as had first appeared, but one that was highly original but consistently imagined.

Smart composed Jubilate Agno as a kind of spiritual diary, in which he recorded his thoughts, memories, and reactions to his surrounding events and outside events (he was able to read newspapers in the asylum). These he set down in a form inspired by Hebrew antiphonal verse, with a line beginning with the word ‘Let’ followed by an answering line beginning with the word ‘For’. Into this structure he poured a remarkable – and frequently bizarre – outpouring of religious certainty, arcane knowledge, pseudo-science, and personal detail.

Let Elizur rejoice with the Partridge, who is prisoner of state and is proud of his keepers.

For I am not without authority in my jeopardy, which derive inevitably from the glory of the name of the Lord.Let Shedour rejoice with Pyrausta, who dwelleth in a medium of fire, which God hath adapted for him.

For I bless God whose name is jealous – and there is a zeal to deliver us from everlasting burnings.Let Shelumiel rejoice with Olor, who is of a goodly savour, and the very look of him harmonizes the mind.

For my existimation is good even amongst the slanderers and my memory shall arise for a sweet savour unto the Lord.

Now this is very strange (though no stranger than the Bible), and clearly entirely private. Smart may have imagined he was writing for everyman, but his only audience was, inevitably and inexorably, himself. Nor is it poetry as such. It is free-form – not in construction, for it abides by careful rules of form, as was typical of Smart’s verse – rather in freedom from any constraint of precedence or habit. Imprisoned by society, he was also set free from it. And amid the strangeness there is much that hits us with the punch that Smart intended.

On his being an object of mockery by visitors to the asylum:

Let Eli rejoice with Luecon – he is an honest fellow, which is a rarity.

For I have seen the White Raven and Thomas Hall of Willingham and am my self a greater curiosity than both.

Some barbed compliments:

Let Nepheg rejoice with Cenchris which is the spotted serpent

For I bless God in the libraries of the learned and for all the booksellers in the world.

The profoundly beautiful and mysterious:

Let Hushim rejoice with the King’s Fisher, who is of royal beauty, tho’ plebeian size

For in my nature I quested for beauty, but God, God hath sent me to sea for pearls

His memories of the happy lands of his childhood:

Let Schechem of Manasseh rejoice with the Green Worm whose livery is of the field.

For I bless God in SHIPBOURNE FAIRLAWN the meadows the brooks and the hills

Or recalling his childhood Durham sweetheart, Anne Vane:

For I saw a blush in Staindrop church, which was of God’s own colouring.

I once went on pilgrimage to the village of Staindrop and its plain church, just to say thank you for the beauty of that line. It is also an example of a line from the work that does not have an accompanying ‘Let’ line. Jubilate Agno was never finished, and some pages are missing from the manuscript (‘Let’ and ‘For’ section were written on separate pages). However, it seems clear that in some cases Smart thought only of the lines in one form without their echo. This certainly seems the case with the work’s most celebrated passage, that which celebrates Smart’s asylum companion, his cat Jeoffry:

For I will consider my Cat Jeoffry.

For he is the servant of the Living God, duly and daily serving him.

For at the first glance of the glory of God in the East he worships in his way.

For this is done by wreathing his body seven times round with elegant quickness.

For then he leaps up to catch the musk, which is the blessing of God upon his prayer.

For he rolls upon prank to work it in.

The seventy-four lines on Jeoffry are deservedly cherished for the sharpness of their observation and the affection that came hand-in-hand with the observation. Smart has a specific religious purpose in celebrating his cat, for he saw animals as engaging in worship as an inevitable outcome of being part of God’s grand design. But he could not help understanding a cat just as a cat.

Jubilate Agno, despite its intermittent beauties, is not a work that most would want to read in its entirety. Some bright minds have analysed every recondite reference, revealing Smart’s interest in everything from personal history to the occult to Newtonian science (to which he was firmly opposed). It is an impossibly intricate puzzle, whose ultimate answer lay only in the head of one man. In English literature perhaps only Finnegans Wake is so similarly mad, bold and lucid, so confident in its unique apprehension of language. And I know which of the two I would rather keep, and read again.

W.F. Stead called the work ‘A Song from Bedlam’, reflecting the common idea of it as being the product of a madhouse. Any study of Smart’s free thinking would make it clear that it was anything other than a product of madness, but undoubtedly Smart’s contemporaries would have come to that opinion had they seen what he was writing. After all, they had had the chance to read A Song to David, his other outstanding product of his asylum years, published soon after his release. Some on reading it pronounced him to be as mad as ever, so strange did some of it seem to be. Yet no saner work was written, and few greater.

A Song to David is that rarity, the perfect long poem. ‘Perfect’ is usually a meaningless term of high praise, but in the case of Smart’s poem it was his intention, and his achievement. His theme and his aim were faultlessness. For the poem, Smart applied everything he knew about poetry and its relation to theology. It is an example of that one work that the determined artist knows that they have in them, where everything goes right. I think of Ford Madox Ford’s dedicatory letter to The Good Soldier, where he writes that before then “I had never really tried to put into any novel of mine all that I knew about writing … So, on the day I was forty I sat down to show what I could do – and The Good Soldier resulted.” Smart’s greatness lies in the fact that he achieved that one all-knowing work twice, with Jubilate Agno and A Song to David, in two radically different ways.

A Song to David is a song of praise to the the David of the Bible, which is as much a song delivered by David, in whom Smart identified strongly. Smart translated all of the psalms of David (efficiently rather than expertly, it must be said), and in his many hymns, odes, songs and prayers he played out the role of David as he saw it, a boy (or little man) in a world of Goliaths whose one true purpose was to sing out the truth (as Smart saw it).

However, one does not need to have knowledge of, or sympathy for, religion, to appreciate A Song to David and its intelligent design. Its intricate ordering is at once mysterious and lucidly clear.

O THOU, that sit’st upon a throne,

With harp of high majestic tone,

To praise the King of kings;

A voice to heaven ascending swell,

Which, while its deeper notes excel,

Clear, as a clarion, rings:To bless each valley, grove, and coast,

And charm the cherubs to the post

Of gratitude in throngs;

To keep the days on Zion’s Mount,

And send the year to his account,

With dances and with songs:O Servant of God’s holiest charge,

The minister of praise at large,

Which thou mayst now receive;

From thy blest mansion hail and hear,

From topmost eminence appear

To this the wreath I weave.

How to praise praise? One can point to the particular stanza form and metrical measure set out in these opening lines of the poem, but these are mere means to an end. As the reader proceeds through the poem the ingenuity of its architectural design becomes clear, with thematic grouping of stanzas on the seven pillars of knowledge, the twelve virtues of David, the four seasons and the five senses. Lovers of numerical mystery can have a field day with the poem (much ink has been spilled trying to detect the poem’s supposed links with Freemasonry). But, again, the design is only there to serve a purpose, which is clarity. It is poem which makes things clear. This is manifest in the immaculate language of those opening lines which sing out as they are read.

A Song to David proceeds to enumerate the virtues and accomplishments of David (“the best poet which ever lived” as Smart describes him in the poem’s contents list, which says something about Smart’s own visions of himself), building up its argument as in the building of a great building. It is a profoundly architectural poem. The sense of building is expressed as a rising tone through the work, as the edifice reaches its apex – after two stanzas where each line starts with the word ‘Glorious’ – with its triumphant final stanza:

Glorious – more glorious is the crown

Of Him that brought salvation down

By meekness, call’d thy Son;

Though at stupendous truth believ’d,

And now the matchless deed’s atchiev’d,

DETERMIND, DARED and DONE.

The extraordinary effect of this final stanza can really only be appreciated after reading all that precedes it. It start with the sense of having reached a plateau after all that building upwards, yet there is a contrary sense of falling in that third line, triggered by the word ‘down’ and the change in metre. The stanza both lifts the reader and makes them fall. It is pure vertigo. Then follow two lines of standing back to take in the immensity of what has been constructed, and then the strongest last line in English literature – the language’s greater translation of Veni, Vidi, Vici, and the three final blows to complete the building. Smart has shown us all that he can do. No other end was possible.

Christopher Smart wrote other poems of charm and skill, though it takes some patience to find them among the morass of mediocre if technically competent verse that he produced. The Hymns for the Amusement of Children can be delightful, if a little too theologically abstruse for their supposed audience; Ode to General Draper is among the best of his praise poems to ordinary mortals (I treasure a gentle line wishing him “A little leisure for a thankful heart”); On An Eagle Confin’d in a College Court explores its metaphor most astutely; and his classically-turned encomium to the county of his birth, The Hop-Garden is as moving as it is occasionally absurd. I’m not so sure about “the voluminous Medway’s silver wave” nor of the wisdom of coming up with the idea of “Tunbridgia’s salutiferous hills” (he means the lands around Tonbridge are healthy). Look closely, and there are moments of touching sorrow over his land of lost content, when God’s design seemed clear:

Oft I’ll indulge the pleasurable pain

Of recollection; oft on Medway’s banks

I’ll muse on thee full pensive; while her streams

Regardful ever of my grief, shall flow

In sullen silence silverly along

The weeping shores…

However, the absurdity is also a part of the appeal. It makes clear Smart’s struggles to manage the realities of existence in an increasingly rational world. Smart wanted all things to be elevated: language, belief, his own little self. Too seldom did others hear him the way he wanted to be heard when he sang. His poetry is not questioning; instead it aims to be revelatory. Only on rare occasions does he truly succeed in this. Ironically or not, it took incarceration in an asylum for Smart to make his song clear.

This is the fourth in an occasional series of posts on favourite poets of mine

Links:

- There is a good long introduction to Smart’s life in poetry by Karina Williamson on the Poetry Foundation site

- There are several Christopher Smart poems on the Eighteenth Century Poetry Archive, including A Song to David and The Hop-Garden

- Smart’s original manuscript for Jubilate Agno can be browsed page by facimile page on the Harvard Library Viewer

- The Selected Poems from Penguin (though now out of print it seems) has good background notes on the poems, with explanation of the arrangement of Jubilate Agno, which the volume includes in full