What is the connection between Balzac’s The History of the Thirteen, Lewis Carroll’s ‘The Hunting of the Snark’, and Aeschylus’ Prometheus Bound? Answer – there isn’t one. Or rather there is, in that all three are specifically referenced by Jacques Rivette’s improvisational epic set of films, Out 1 (1971), but whose chief purpose might be said to be to show that there is no connection.

Out 1 is one of the lost legends of cinema. Nearly thirteen hours in length, it was barely shown at the time of its first release in 1971 (Rivette optimistically hoped it might be picked up by French TV). A shortened version, at a mere four hours long, entitled Out 1: Spectre, became a little more widely available, but the full film disappeared into legend. A restored version was produced in 1990, but it was not until around ten years ago that it started to get shown in festivals and retrospectives, and only this year that it appeared on DVD. I saw it on the arthouse subscription service Mubi, divided into four parts (the film comes in eight episodes). It’s a badge of honour for any cinéaste to say that they have seen it.

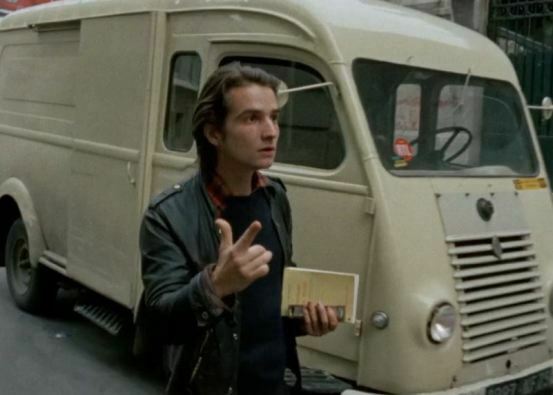

The film has four narrative strands that eventually interlock. Two strands come out of two theatre troupes, both rehearsing plays by Aeschylus: one doing Prometheus Bound, the other Seven Against Thebes. A young man, apparently a deaf-mute, played by Jean-Pierre Léaud, begs for money in restaurants while seeking evidence of a secret society. A young woman, played by Julie Berto, robs men through trickery, partly for survival and partly for the fun of it. Gradually the four strands and their many characters start to come together, linked by the actual existence of the secret society, ‘The Thirteen’, which seems to be defunct though a number of whose members are characters whom we have been following throughout the film. In the end – insofar as there is an end – the two troupes give up on their rehearsals, the young woman is shot dead, and the young man returns to his begging, having convinced himself that The Thirteen does not exist.

The film is sort of based on Balzac’s three short novels known collectively as Histoire des Treize, or History of the Thirteen, about a secret society of thirteen men who operate above and beyond the law. However, there is little actual connection with Balzac (despite Léaud’s character carrying a copy of the book around with him). Instead the idea of the secret society provides a framework upon which the four scenarios hang, and out of which a improvisatory unfolding of the story (for want of a better word) occurs.

Because Out 1 is all about improvisation. Pretty much all the way through they are making it up as they go along, because that’s what we all do. There are narrative milestones, interelationships and point of conflict that are introduced to give some direction to the performances, but in between these points the actors came up with the personalities they wanted to portray and the words to fit the situations.

At times this is mesmeric; at other times it is baffling, and occasionally excruciating. In particular we see an awful lot of the two theatre troupes, who are of the po-faced experimental kind. They spend a lot of time screaming, dancing, miming, engaging in free association of ideas, or just plain staring at one another, all of which they then sit about and analyse in prolonged depth. We see very little of Aeschylus at all, and though there might be some connection with the sufferings of Prometheus and the anguish of some of the performers, frankly the connection is not a clear one. It certainly seems that they have no intention, or hope, of ever putting the plays before an audience.

So what is Out 1 about? It doesn’t seem to be about anything. The write-ups on the film usually suggest that it tells about post-1968 Parisian malaise, but you’d have to be told that to see it, and even now that I’ve been told it I still don’t see it. Instead they all seem to exist out of time, out of anything concretely recognisable at all (Rivette called the film Out to contrast with the vogueishness of the word ‘in’). There is a recognisable world that we see going on in the background; a mundane Paris of workers, traffic, cafe-dwellers, shop-keepers and puzzled passers-by who fail to dodge out of the way of the camera in time (the improvisatory spirit extends to the rough-and-ready filming style, in which we often see the shadows of the camera crew, cuts between the strands often seem arbitrary, and all manner of rough edges are allowed to remain). The characters – none of whom appears to need to work for a living – exist in an unreal bubble, which the outside world can see through while not understanding what it is seeing.

The Lewis Carroll references come when Léaud’s character is searching for clues to the existence of The Thirteen and finds coded references to ‘The Hunting of the Snark’. The use of cyphers, the secret society haunting Paris, and Berto’s amoral heroine made me think that maybe there was an intended affinity with Louis Feuillade’s Les Vampires (1915), another long film story told in serial form, about a mystery criminal gang preying on Paris. It’s a film that is specifically referenced in Jacques Rivette’s Celine and Julie Go Boating, so maybe there’s something in it. As with Balzac, the association seems more convenient than significant.

For all of its faults and absurdities, Out 1 is compelling to watch. This is largely due to the intensity of the performances. The actors never for a moment make us think that this fragile illusion is anything other than the reality they understand. Jean-Pierre Léaud, Julie Berto, Bulle Ogier as a mysterious woman living under two names, Michael Lonsdale as the tortured leader of the Prometheus Bound troupe and Eric Rohmer, no less, as a Balzac specialist, stand out in particular. The performers show that Out 1 is not about secret societies, or post-68 Paris, or the titan who stole fire from heaven and was punished for it by the gods. Its purpose lies in its method, a set of characters let loose to reveal themselves and discover the connections they have with one another. It works best, however, before they have discovered those connections. In the latter stages of the film there are more revelations and plot resolutions, while the the filming style becomes less random and a times almost conventional. The film starts to try and mean something – and is thereby exposed as perhaps not meaning very much at all.

The end of Out 1 didn’t feel like an end. They was no real closure. Instead the feeling I had was that it could have gone on for ever, with nothing decided or completed, just endlessly discussed and altered. I didn’t think it was very good, but I could have kept on watching it indefinitely. So what does that mean?