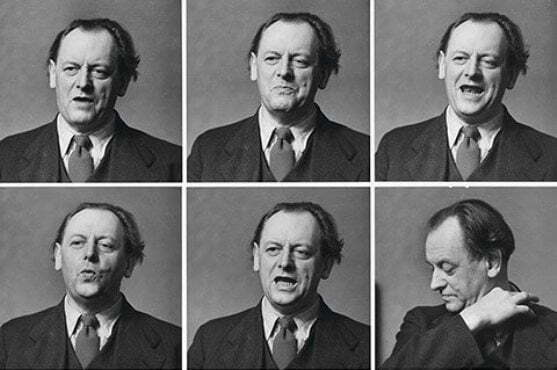

The jazz singer and art lover George Melly was fond of telling a story about when he was confronted by some thugs with broken bottles outside a Manchester club. Running not being much of an option for the rotund Melly, and fighting or negotiating still less so, he chose instead to give a recitation of the ‘Ursonate’, the avant garde sound poem composed by German artist Kurt Schwitters, of which this is a sample:

dll rrrrrr beeeee bö

dll rrrrrr beeeee bö fümms bö,

rrrrrr beeeee bö fümms bö wö,

beeeee bö fümms bö wö tää,

bö fümms bö wö tää zää,

fümms bö wö tää zää Uu

Utterly bewildered by this confrontation with the absurd, his would-be assailants slunk away into the night. Melly later recorded one minute of the piece for Morgan-Fisher’s magnificent 1980 compilation album Miniatures (definitely the subject of a future blog post), pointedly entitling it ‘Sounds That Saved My Life (Homage to K.S.)’. Listen, and quake.

Ever since encountering this I have been a fan of Kurt Schwitters (1887-1948). He was an artist, sculptor, collagist of genius, designer and poet, someone who lived his life true always to the spirit of Dada. It was while on holiday in the Lake District the other week that I had the opportunity to see something of his particular contribution to art and to the British landscape, the Merzbau.

‘Merz’ was a term that Schwitters adopted to describe his collage art, but which expressed a general idea creating art out of found objects. The concept reached a sort of apotheosis with his creation of the Merzbau, an existing physical living space transformed into a work of art. He created three Merzbau. The first, produced over 1923-1937, was the transformation of part of his family home in Hannover. Two whole rooms, an attic room, a balcony and possibly more were filled with sculptural forms, creating a sort of angular cave, at least to judge from the three surviving photographs, as Schwitters fled Nazi Germany in 1937 and the building was destroyed by Allied bombing in 1941.

Video of a recreation of the Hannover Merzbau at Berkeley Museum in 2001, showing how dazzling a use of colour and space it was

The second Merzbau was created in the garden of his home at Lysaker, near Oslo in Norway. It was unfinished when Schwitters left Norway for Britain in 1940, and it burned down in 1951 – with no surviving photographs. (A similar converted living space, on Hjertøya island in Norway, does exist, but was not classified by Schwitters as a Merzbau.)

The third and final Merzbau was created when Schwitters came to Britain, eventually settling in the Lake District in 1945. He lived in Ambleside, and – desperately poor – was obliged to eke out a living producing portraits and landscapes of the conventional kind for residents and tourists. In March 1947 he found a stone barn suitable for a new Merzbau at Cylinders Farm, near Elterwater, one of the smaller but most scenic of the Lakes, beneath the Langdale Pikes. Here – having learned of the destruction of the Hannover Merzbau – he hoped finally to complete his artistic dream.

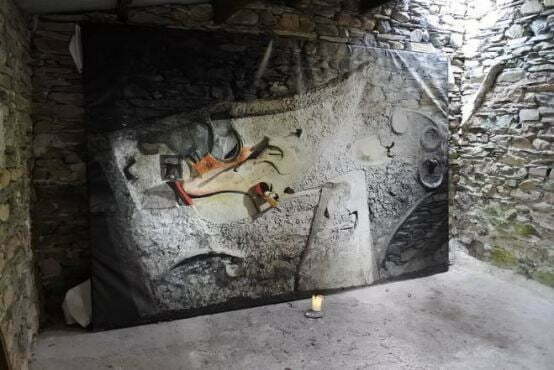

Sadly it was not to be. Schwitters died just a few months later, in January 1948, with little work done on his ‘Merz Barn’. Just one wall had been completed, a combination of found objects and plaster. Intriguing in itself, it gives little indication of how the complete grotto-like effect was to have been created, with three-dimensional objects coming out of the walls, and nooks and crannies within which found objects were to be again found – nor of how the work might have continued as as an ever-changing art piece, constantly (as Schwitters believed was essential) in a state of flux. Not that you can see the one wall that was done – the artwork was removed from the neglected barn in the 1965 with the help of the artist Richard Hamilton and transferred to the Hatton Gallery at the University of Newcastle, where it remains to this day.

The Merz Barn today is both a sorry and a heartening sight to see. If you are starting from Ambleside, catch the bus to Chapel Stile, then walk back down the road to the Langdale Hotel. Opposite the hotel entrance is a green gate, with the words ‘Merz Barn Kurt Schwitters 1947’ engraved on slate on the wall. You enter, go right past a farm building, then up a path to an unprepossessing single storey stone building with a handsome plaza to the side of it, with a central tree root feature. Inside the building, with a corrugated metal roof and lit by two windows, there is nothing bar a chair, small table, and a full-scale photographic reproduction of the artwork on one wall that is no longer there. There is a candle on the floor lit in homage. Adjoining the main room is a battered-looking smaller space with some plasterboard and paintbrushes. To the right of that is an exposed section of the building where a glass-roofed annexe should be, with random pipes, wood and a ladder. It is no one’s idea of a great art statement, and suggests little to the imagination of ever having promised to be such a thing.

When I visited the sorry-ness had been exacerbated by Storm Desmond, which had wreaked havoc across the Lake District in January 2016. The large tree had been uprooted next to the building, the annexe with the glass-roof was smashed, and the main roof was in a poor state. The storm had smashed all of the windows, thanks to flying branches, and flooded out the main room and adjoining Cake Room. The back wall was left in a state of near-collapse.

There was little fury in the elements when I visited, on a fine sunny day. Happily that very week news had come through of a £25,000 gift from the Galerie Gmurzynska in Zurich, in response to a funding appeal and thanks to a suggestion made to the gallery by the late Zaha Hadid. Together with £5,000 from the University of Cumbria and £15,000 from the Cumbria Community Foundation, there is money enough for them to begin to repair damage caused by the storms.

The heartening side of the Merz Barn is seeing great enthusiasm with which it is being cared for. It is looked after by the Littoral Arts Trust, a non-profit body with the ambition of turning the site into an art museum and major tourist attraction. It has organised summer schools, open days, seminars, lectures and happenings, and deserves great praise for its dedication and professionalism. The place is acquiring the status of a shrine. Artists come in pilgrimage and are wont to leave their own contributions behind. Apparently this is not encouraged, but I saw some small crafted objects inserted among the stonework outside.

I hope the plans come to fruition, though the result will be more a celebration of Kurt Schwitters than what he had actually planned. The isolation of the barn must have been part of the appeal for the artist, and back in the winter of 1947 (a notoriously harsh one), and before the Lake District became quite such a tourist magnet, the site must have seemed especially remote. It would have been an adventure, even a battle, to locate it, then to discover inside the joyous expression of an unfettered imagination, had that imagination been allowed to live a little longer.

We find art in tamed form in galleries. In such spaces it conforms to our expectations. Land artists such as Richard Long and Andy Goldsworthy have taken art back to nature by marrying artworks with the landscape, but the Merz Barn was to have been something more. It was a pure expression of found art, not just in its construction but in its location. It was the art of surprise. It was that which was key to George Melly’s recitation of the Ursonate. It wasn’t just the reading of the poem, but that the fact that it was read where it wasn’t expected to be read, overturning any sense of what is real and what is art. Melly’s action was a work of art in itself, a Dadaist statement of which Schwitters himself would have been proud.

I hope the Merz Barn survives the elements and finds the money that will secure its future as a place of pilgrimage. But as a work of art it is as lost as the other Merzbaus, for all the efforts of our recreations – a found object destined never to be found again.

Links:

- There is a an excellent Merz Barn project website, with history, news, information and copious illustrations – see https://merzbarnlangdale.wordpress.com (it includes a sound recording of Schwitters himself reciting the Ursonate)

- The Kurt Schwitters archive is held by the Sprengel Museum in Hannover (site in German and sadly not as well-illustrated as it could be)

- There is a web page from the Hatton Gallery on its Merz Barn Wall

- The Tate has a well-illustrated paper by Karin Orchard documenting various reconstructions of the Hannover Merzbau