The film programmers among you (real and imaginary) will have noticed that 2016 sees the 400th anniversary of Shakespeare’s death, and there is an obligation to show something of the man’s works on your screens. With a heavy sigh you turn to the obvious Branaghs and Oliviers, with just maybe Forbidden Planet (perhaps the best-known Shakespeare-derived feature film) for a touch of light relief from all that staginess and blank verse.

But look again! Shakespeare films can be the most marvellous things if you look beyond the obvious (though the obvious can be marvellous too – I wouldn’t want you to turn your backs on Olivier). I am all for the films whose debt to Shakespeare is oblique, elusive, or something more than just a restaging or a plot parallel. Such films present us with a rewarding mystery to solve. So here are three Shakespearean favourites of mine, which never – I think – get mentioned in the voluminous literature we now have about Shakespeare on screen, but each for me are among the best sort of Shakespearean cinema.

Détective (France 1985)

Jean-Luc Godard made two Shakespearean films in the 1980s. King Lear (1987), of which I have only seen fragments, is notorious for its bizarre cast (Woody Allen, Norman Mailer, Molly Ringwald) and for appearing to have not much to do with King Lear. But look at Détective, which has long been one of my favourite of all Godard’s films. Set in a hotel, the film tells of a detective (Laurent Terzieff) trying to work out who killed a guest there two years previously. The narrative, involving a boxing promoter (Johnny Hallyday), a pilot (Claude Brasseur), his wife (Nathalie Baye) and a mafia boss (Alain Cuny) is almost impossible to follow, and indeed not necesary to follow. It is a film where you have to admire the fragments rather than to try grasp the whole.

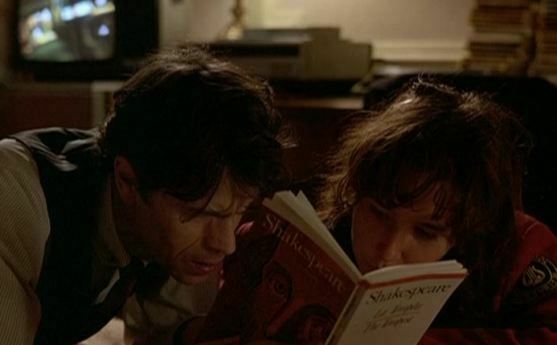

But what is the detective’s name? William Prospero. And his assistant is called Arielle, and they look for clues in Shakespeare’s text – indeed the film’s character spent much of their time reading from assorted literary texts in the hope of finding clues, but it is The Tempest that binds it together. Détective is not a roman à clef with The Tempest as its key – one does not better understand the film for knowing Shakespeare’s play, still less is it a transposition of Shakespeare’s plot to a modern setting. But the play does hold a special place in Godard’s design. Détective is a kind of counterpoint to The Tempest, in which the magician detective seeks control of his island by trying to piece together its story. He grasps what has happened, but loses us in the process. The film’s realisation does not bring resolution, in the way that Shakespeare’s play does, only confusion.

On the BFI’s DVD release Colin MacCabe unwittingly (?) describes the film as Godard’s ‘farewell to cinema’, since he largely abandoned narrative filmmaking thereafter, much as we think we see Shakespeare in Prospero saying farewell to the theatre – except, like Godard, he carried on. What artist can ever say that from this point they must stop? What happens to the detective when he has solved the mystery? He lives for the quest, not (as he may think) for its conclusion. One should look at Détective not as an interpretation of The Tempest, but rather as an oblique invitation to look the play with new eyes.

A Matter of Life and Death (UK 1946)

Michael Powell and Emeric Pressburger’s masterpiece is an artfully constructed cinematic puzzle. Ostensibly it is a romance between a British pilot and an American radio operator with a fantastical setting on earth and heaven, designed with the aim of cementing Anglo-American relations after the Second World War. but it lays out a maze of clues by which we can try to piece together (much as Godard’s detective) what is really going on. Why the references to Andrew Marvell? What does the camera obscura signify? What so much medical detail? Why the interest in table tennis, and chess? Why the speeding motorbike? And what is Shakespeare’s A Midsummer Night’s Dream doing there?

The specific reference is brief. We see some American soldiers stationed in Britain rehearsing a scene from Shakespeare’s play, reflecting that obvious theme of the cross-fertilisation of American and British culture. But of course there’s much more. The vicar who is directing the players is Robert Atkins, famous for producing Shakespeare’s plays at the Regent’s Park open air theatre, which is best known for its many productions of A Midsummer Night’s Dream. The scene they are rehearsing is the ‘Pyramus and Thisbe’ play-within-a play (and this is a play within Powell and Presburger’s play, of course). The scene is about two lovers trying to communicate through an (imaginary) wall – which is a very good way of describing the romance between Peter Carter (David Niven) and June (Kim Hunter).

And there’s more. Peter Carter is a poet whose sanity is questioned because of the visions he sees. Theseus, in Shakespeare’s play, tell us that “The lunatic, the lover, and the poet / Are of imagination all compact”, describing Peter perfectly. A Matter of Life and Death could easily be subtitled A Midsummer Night’s Dream, and not just because it takes place in mid-summer. Peter spends much of the time asleep, so that we are not sure whether his dreams are real or fantasy. Shakespeare’s play is constructed in the same way: characters continually falling asleep, so that the fairy figures that then appear can be both stage reality and human fantasy.

You can go on and on with this. Is the heavenly messenger Conductor 71 a version of Puck? Are the Judge and Chief Recorder versions of Theseus and Hippolyta, lording it over the mere mortals? There is no better film for understanding that the best Shakespeare films are not necessarily those that reproduce the plays most faithfully, but those that are most imbued with their spirit.

Paris nous appartient (France 1960)

The late Jacques Rivette’s debut feature is set among the earnest young of Paris, with a narrative thread about the mysterious death of a Spanish musician and some marvellously evocative images of lives lived in garrets and street cafés. The central character Anne (played by Betty Schneider) is a student of literature who we first see reading Ariel’s song from The Tempest. But having been given this early sign, we are taken – like Anne herself – in an unexpected direction. She falls by accident into playing the part of Marina in an earnest production of Shakespeare’s Pericles, which then features throughout.

Paris nous appartient is no reimagining of Pericles, however. It would be perverse indeed to expect us to see parallels in a play few have seen or could describe. What matter instead are the character of the play – its fragmentary, difficult character – and specific role that Anne plays, that of the young Marina. The director of the play, Gerard (played by Gianni Esposito) is drawn to Pericles because it is “unplayable”, a thing of “shreds and patches, and yet it hangs together overall”. Anne’s revealing assessment of the play is that “it’s rather disconnected but that doesn’t matter, because it’s on another level”. Pericles was co-written by Shakespeare and George Wilkins, and survives only in a pirated edition taken down from the faulty memory of one of the minor actors in a production during Shakespeare’s time. It is a lost play in that we see what it might have been through the confusion what of what survives, sensing that which is Shakespeare from that which is not.

This half-remembered form of a dramatic work suits Rivette’s approach to cinema, while the method of having a play-within-a-play, as Shakespeare knew, is an excellent means of revealing a reality which is otherwise lost upon the players in the overall drama. The characters in Rivette’s film are largely deluded, caught up in a political world that they think they understand but do not. They are cast adrift, as Marina is in Pericles – the daughter of Pericles, captured by pirates, sold to a brothel, wins over her captors by her purity of character, then is reunited with her father in the play’s harmonious and moving conclusion. Paris nous appartient is not Pericles (not least because the film ends in disillusion and disharmony), but Anne is Marina – the lost survivor.

In all three examples, both film and play encourage us to think about the relationship between narrative and character, literature and film, artifice and reality, each subtly sharing in the other’s mysteries. All three offer a mystery through the device of Shakespearean allusion, in which the pleasure lies in never quite being able to pin down the exact relationship between play and film. The more we look, the more we detect, and the more we have to look again.

Thank you Luke! Very interesting. Working on Shakespeare in the Nouvelle vague, and published a piece on Paris nous appartient. You’re right, not many people are aware of Detective and the Shakespeare intertext. (In fact I came across this post precisely because I wanted to check if people had written on this).

I love the film and I love trying to work out what Shakespeare is doing there. Has anyone else written about the relationship between Détective and The Tempest? Have you?