I have spent the past few months reading Sir Steven Runciman’s three-volume A History of the Crusades. It’s one of those works that has sat on the shelves for a long while, daring me to find the stamina to read through all 1,430 pages. But one day – to be precise, it was the day of the closing ceremony of the Olympic Games, when I could not bear to look at the television screen any more – I launched in, and, with several diversions along the way (I usually have three books on the go at any one time) I reached the end last week.

And what a desperate tale of human folly it all is. One is brought up knowing bits here and there about the Crusades, from tales of Richard the Lionheart and Saladin, to feature films, history programmes, encyclopedia entries, and a vivid childhood memory of reading Henry Treece’s hugely sad The Children’s Crusade. I had the Crusades in my head, but in no sensible order. To read the story of the main Crusades and the various sub-Crusades between 1095 and 1272 is to be overwhelmed the stupidity of it all. The Crusaders were violent, immoral, greedy, vicious, deceitful, cruel, hypocritical, bigoted, but above all stupid.

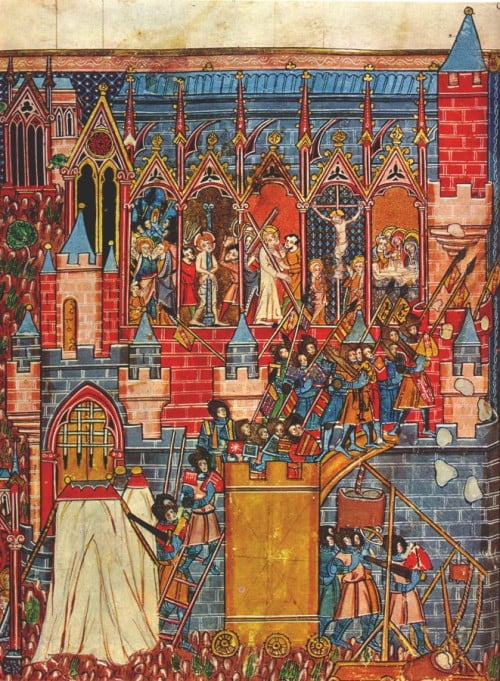

The Crusades were a venture from which nothing was learned, and nothing gained. Each wave of Crusaders poured into the Near East lands, determined to slaughter the Infidel, settled down, started to become assimilated to the ways and means of the East, then a new wave would come, express disgust at the lax ways of their brothers-in-arms, and start the slaughter all over again. But they weren’t even very good at the slaughter, falling into ambushes over and over again, their belief in charging headlong at the enemy being regularly exploited by an enemy that simply made a tactical retreat, then counter-attacked once the Crusaders had been lured into disadvantageous territory. They would not shed the belief that they could not fail because God was with them, a belief reinforced by the seemingly miraculous success of the first Crusade which ended with the conquest of Jerusalem, yet they failed and failed again. They seem to have had no grasp of political strategy, most noticeable in their contempt towards the fellow Christian state of Byzantium, which was an essential buffer against the Seldjuk Turks, yet which the Crusaders never trusted and eventually destroyed in the grotesque parody of the Fourth Crusade.

The lack of any honour is particularly striking. Over and again you read of a besieged fortress, of the defenders surrendering on the understanding that they would be allowed to walk away unharmed, only for the victorious leader to go back on his word and have them all killed in any case. Personal, familial or tribal advantage outweighed any other consideration, and could be twisted to justify any outrage. How could one live in such a world?

And then there are the massacres. To read the history of the Crusades is to wade in blood. When the Crusaders captured Jerusalem in 1099, practically the entire population of the city was slaughtered – estimates range between 10,000 and 40,000 people. According to the code of the times (in a time without much in the way of codes this was one that all seemed to adhere to, most of the time), a besieged city’s inhabitants should be spared if they surrendered with a reasonable period of time; if they resisted, and the siege was successful, they they had to suffer the consequences, as the victorious troops were allowed a period to gather booty and slaughter and ravage as best suited them for a set period (three days seems to have been the going rate).

At least one million people were killed during the Crusades. Thousands were killed in each wave of invasion and counter-invasion. Repeatedly the history tells of gung-ho Crusader armies attacking when wiser counsels tried to advise caution, only to be massacred by the Moslem forces who must have been baffled by an opponent who never listened, never learned. What you don’t get from Runciman’s history is a sense of the proportion of troops killed on their side, compared to the size of the armies overall, or how much wastage there was of the civilian population. How did life sustain itself? How could one live in such a world?

It is the civilian massacres that are the most upsetting. Behind every bald account of some many thousand killed at the falling of some city are countless individual tragedies. Young, old, women, children, of every religious persuasion or tribal identity, all fell to the sword or some other brutality (mutilations, blindings and so on). If they weren’t killed, they were enslaved. They expected such a fate, because that was how the world was, and it is noticeable how often besieged cities would refuse to surrender, valuing their honour or their special identity above any calls to give these up (though such shows of defiance may have come more from their leaders than the commonfolk). But what did the children know of such honour or identity? You were just trapped in a world where everyone who decided that you were of a kind that was not like them would therefore kill you if given the opportunity, and violently so. Violence was the expression of certainty.

There’s not much comfort to be gained from such a history, so you look for understanding. Runciman sums up the Crusading movement as “a vast fiasco”, the consequence of “faith without wisdom”. This makes it a moral failure, which is an interesting conclusion that perhaps belongs more to the time in which Runciman wrote (his three volumes were published 1951-1954) than one would get from a historian today. A military historian such as John Keegan, in his A History of Warfare, sees the the rise and fall of the Crusader armies as one of changing tactics, their early successes being due to the advantages that armoured soldiers had over light cavalry, a situation overturned when Saladin and then the Egyptian Mameluke powers with the “evasive, harrying tactics of the steppe horsemen” outwitted the blinkered methods of the Crusaders. An economic historian would see the landless younger sons of Europe’s gentry driven to the Crusades to obtain territory denied to them by existing market forces, while humans on the field of conflict were mere objects of exchange, to be eliminated or else enslaved or sold. Such conclusions see the ebb and flow of history as one of tactical, commercial or mechanical advantage. It does not tell us why people acted in the way that they did, and why so horribly.

Steven Pinker’s recent book The Better Angels of our Nature looks at the history of violence, and argues that we are living in the gentlest of ages, because overall progressively fewer people get killed year by year. He presents this argument as though it is something startling, assuming that his readership will hold it that we live today in the worst of times. Notwithstanding the fact that the twentieth century saw the conflict which killed more people than any other in history (the Second World War), it seems fairly obvious that we live in – for the most part, and in most places – pacific, civilised times. I can go about my daily business without fear of attack or invasion, without the feeling that I must kill or be killed. Yes there are absolutists about who still think in a killed-or-be-killed way, but statistically I live in better times. How did we change, or are we the same people as those in the eleventh century, only brought up differently?

Pinker starts with the facts and figures that show that we have progressively slaughtered one another less and less as the centuries have progressed. He then tries to find out why. His guiding text is Norbert Elias’ classic sociological study, The Civilizing Process. This is one of the great books of our times. Elias traces the processes by which we have gradually suppressed our baser instincts over time. He homes in on such entertaining subjects as table manners, spitting, bodily functions or bedroom behaviour in the Middle Ages, and how gradually the idea of manners, or hiding one’s behaviour on occasion, progressively took hold, usually starting with the gentry and then working its way down. Then he turns to the question of aggression and violence, and finds the answer for it in the structures of society. Here’s what he says about the aggressive instinct in the Middle Ages:

Not that people were always going around with fierce looks, drawn brows and martial countenances as the clearly visible symbols of their warlike prowess. On the contrary, a moment ago they were joking, now they mock each other, one word leads to another, and suddenly in the midst of laughter they find themselves in the fiercest feud. Much of what appears contradictory to us – the intensity of their piety, the violence of their fear of hell, their guilt feelings, their penitence, the immense outbursts of joy and gaiety, the sudden flaring and the uncontrollable force of their hatred and belligerence – all these, like the rapid changes of mood, are in reality symptoms of one and the same structuring of the emotional life. The drives, the emotions were vented more freely, more directly, more openly than later. It is only in us, in whom everything is more subdued, moderate and calculated, and in whom social taboos are built much more deeply into the fabric of our drive-economy as self-restraints, that the unveiled intensity of their piety, belligerence or cruelty appears to be contradictory. Religion, the belief in the punishing or rewarding omnipotence of God, never has in itself a “civilizing” or affect-subduing effect. On the contrary, religion is exactly as “civilized” as the society or class which upholds it.

It was a time when “the structure of affects was different from our own, an existence without security, with only minimal thought for the future”. For Elias, what caused the civilizing process was – broadly speaking – the formation of states and the rise in commerce. Living in such states, with their controls and their particular interrelationships, brought about restraint, inculcated self-control. Pinker picks up on this, examining Elias’ thesis with reference to neurological studies, economics, psychology, evolutionary biology and social investigations. He concurs that self-restraint has become second nature to us, “a stable trait that differentiates one person from another, beginning early in childhood”. Impulses toward tribalism, moralism, the revering of one sacred thing above another, all still exist and seem at some level fundamental to human thinking, but the majority think first to exercise restraint. And so we are able to call ourselves civilised.

There are others reasons too – the rise in literacy, communications, social interaction, scientific and industrial advances, the change in the position of women in society. It’s a complex picture, and still more complicated when one considers (as Pinker does at length) whether this means there has been environmental or genetic change. Have we evolved into better beings, or are we merely creatures of the social structures that now sustain us? Elias and Pinker tend towards the latter, though Pinker ranges at length on the possibility that we are measurably more intelligent than our forebears, that our ability to reason and to act with a sense of consequences shows how as a race we have may have moved on biologically. He goes so far as to call our ancestors “morally retarded”.

Many of their beliefs can be considered not just monstrous but, in a very real sense, stupid. They would not stand up to intellectual scrutiny as being consistent with other values they claimed to hold, and they persisted only because the narrower intellectual spotlight of the day was not routinely shone on them.

The Crusaders did not think of consequences, did not listen to such wise counsels as did exist, could not act for what was ultimately to their long-term advantage. They were stupid.

But what was it like being a mother with a child, trapped in a besieged Syrian city, powerless, hearing the shouts of the besieging army outside the walls, hearing the crash of the rocks hurled from siege weapons that sought to batter down those walls, hearing from one’s leaders that death was to be expected and all that there was to do was to fight and to believe, to see the gates fall and the enemy pour in, with licence to do whatever they wanted to do and devoid of any sense of mercy? What was it like, knowing that the blade would fall? How could one live in such a world?

The sociologists cannot answer this, nor the military or economic historians. How could they live? How do they live in the Congo, in Somalia, in Syria today? They live because they have to live. And they serve as reminder that the line between ourselves and our violent forebears is a thin one.

Links:

- The Metropolitan Museum of Modern Art has a succinct history of the Crusades with accompanying thematic essays, maps and timelines

- The Norbert Elias Foundation site tells you about his work, influence and theories.

- Wikipedia’s list of the casualty count of battles in world history is sortable by battle, conflict, number of casualties and year