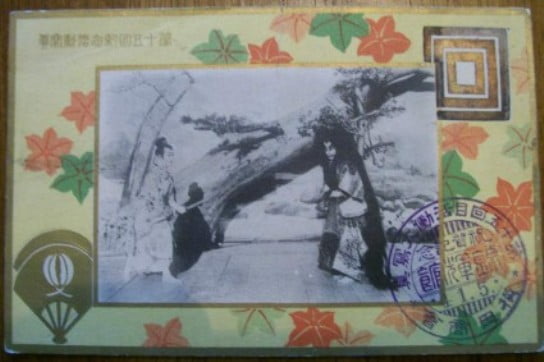

This is an extraordinary image. It’s a Japanese postcard dating from 1908 (the postage stamp says Meijii 41, which is 1908). However the image that it shows dates from November 1899. It shows on the right the greatest of all kabuki actors, Ichikawa Danjuro IX (1838-1903), and on the left Onoe Kikugoro V (1844-1903), second only in fame at the time to Danjuro. They have been photographed in a scene from the dance drama Momiji-gari, translated as Viewing Scarlet Maple Leaves or Maple Leaf Hunters. And the reason the drama was performed because it was done for a motion picture camera.

Projected film first came to Japan when businessman Inabata Katsutaro, a friend of Auguste Lumière, played host to Lumière operator François-Constant Girel, who gave a film show at the Nanchi Theatre in Osaka on 15 February 1897 (peepshow Kinetoscopes were exhibited in Japan in 1896). Film was an immediate hit with Japanese audiences, and several Japanese entrepreneurs enthusiatically adopted the new medium, among them Yokota Einosuke, Kawaura Ken’ichi and Arai Saburo.

It was Arai who was the first person to approach Danjuro with a proposal to film him, in 1897. Danjuro IX (left) was a legend of the kabuki theatre, ninth in an unbroken line of actors named Danjuro, and considered one of the greatest of all Japanese actors. He did much to preserve the art of kabuki and to raise the status of actors generally. However the actor, a deeply conservative character, reacted to Arai’s proposal with repugnance, refusing to have anything with a ‘shipbrought thing’ (thus equating the cinematograph with any other kind of foreign goods).

It was Arai who was the first person to approach Danjuro with a proposal to film him, in 1897. Danjuro IX (left) was a legend of the kabuki theatre, ninth in an unbroken line of actors named Danjuro, and considered one of the greatest of all Japanese actors. He did much to preserve the art of kabuki and to raise the status of actors generally. However the actor, a deeply conservative character, reacted to Arai’s proposal with repugnance, refusing to have anything with a ‘shipbrought thing’ (thus equating the cinematograph with any other kind of foreign goods).

Two years later, Danjuro was sixty years old, and his manager Inoue Takejiro, was anxious to record his great art for posterity. On the understanding that such a film would go into his private vault and not been seen by the sort of commonfolk who frequented film shows, Danjuro assented. A film would be made of part of the dance play Momiji-gari, with Danjuro playing an ogress who has disguised herself as a princess (male actors always play female roles in kabuki) and Onoe Kikugoro V as the hero Taira no Koremochi. Wikipedia gives this summary of the plot of the original play (not the film, which could only show a part of the drama):

The original play, performed in both noh and kabuki, is a story of the warrior Taira no Koremochi visiting Togakushi-yama, a mountain in Shinshū for the seasonal maple-leaf viewing event. In reality, he has come to investigate and kill a demon that has been plaguing the mountain’s deity, Hachiman.

There he meets a princess named Sarashinahime, and drinks some sake she offers him. Thereupon she reveals her true form as the demon Kijo, and attacks the drunk man. Koremochi is able to escape using his sword, called Kogarasumaru, which was given to him by Hachiman. The demon gnaws on a maple branch as she dies.

(A longer summary is available on the Kabuki21 site)

The filmmaker selected to create this important document was Shibata Tsunekichi, who had previously made films of geisha dances. Shibata employed a Gaumont camera and left this account of how the film was made:

There was a gusting wind that morning. We decided to do all the shooting in a small outdoor stage reserved for tea parties behind the Kabuki-za. We hurriedly set up the stage, fearing all the time that Danjuro might suddenly change his mind again. Every available hand, including Inoue, was called upon to hold the backdrop firm in the strong wind. Danjuro, playing Sarashi-the-maiden, was to dance with two fans. The wind tore one from his hands and it fluttered off to one side. Re-shooting was out of the question so the mistake stayed in the picture. Later people were to remark that this gave the piece its great charm.

The film was kept from public view, as had been Danjuro’s wish, but a year later it was shown to an audience of kabuki actors. According to historian Hiroshi Komatsu, the film was first shown to a general audience on 7 July 1903 when Danjuro fell ill and was unable to appear on stage. He died in September of that year. Happily the film has survived for posterity to treasure (it is held by the National Museum of Modern Art in Tokyo) and when it was shown at the Pordenone silent film festival in 2001 (where I missed it) this description of the six-minute, three-scene film was provided in the catalogue:

The first shot, in which Princess Sharashina dances with a fan, is viewed head on, as though she were center stage. The second shot, of the “Yamagami scene”, captures Koremori (played by Kikugoro) in the foreground and Yamagami’s dance behind Koremori. The third shot is from the same camera angle as the first, and shows Koremori and the ogress’s dance.

This is where the postcard comes in, which documents the film’s third scene.

The postcard definitely shows Danjuro IX and Onoe Kikugoro V performing for the Momiji-gari film. It has been photographed in the open air, as one can see from the shadows thrown by the sunlight. Clearly Shibata not only commemorated the event in film but took a photograph (maybe more? maybe three, one for each scene?) at the same time. The postcard, however, dates from 1908, with the legend stating something along the lines that it had been produced to honour the fifth anniversary of his passing. It seems that the production was a little more planned and commercial in intent than the anecdotal histories have suggested. Certainly Danjuro was the subject of innumerable ukiyo-e prints, which suggests an awareness of the importance of image.

There is an interesting parallel with what happened in Britain at almost exactly the same time. In September 1899 the renowned actor-manager Herbert Beerbohm Tree was persuaded by the British Mutoscope and Biograph Company to appear before the Biograph camera in short scenes from Shakespeare’s King John, the play he was presenting at the Her Majesty’s Theatre in London. Four scenes from the play were filmed, which did not tell the whole story but rather showed key points from the drama, just as with Momijigari. In another parallel, a set of promotional photographs were also taken at the same time. Tree was never so fastidious as Danjuro, and his intent was probably more commercial than concerned with posterity, but it is worth noting the coming together of the new medium with the old, the former gaining kudos by association with the other and showing the advantages that it had – to capture performance and defy time. It also demonstrates an idea of cinema as filmed theatre which was to influence Japanese film for several years thereafter, impeding its development as an independent art form for two decades or more.

I am able to reproduce the postcard by kind permission of a US collector by name of Dan. My thanks to him also for translations from the Japanese. The postcard is also reproduced on the Ukiyo-e Prints website, and I am grateful to its host Jerry Vegler for being so helpful, and to Stephen Herbert for having first brought the card to my attention.

There are biographies of Danjuro IX on the Who’s Who of Victorian Cinema site and on Portraits of Modern Japanese Historical Figures. Much of the historical information in this post comes courtesy of Peter B. High’s article ‘The Dawn of Cinema in Japan’, Journal of Contemporary History, vol. 19 no. 1 (January 1984), with acknowledgment also to Hiroshi Komatsu’s notes for the 2001 Pordenone catalogue and his essay ‘Questions Regarding the Genesis of Nonfiction Film‘.

Extensive information on kabuki – the performers, theatres, stories and characters – can be found on the Kabuki21 site. You can get an idea of how Momiji-gari would have been performed from this Daily Motion video which shows a modern-day production in Paris (showing the finale of the drama as depicted in the postcard).

Kabuki à Paris3-5 by abricot5725

Finally, it was recently suggested that the film be designated by the Japanese government as an Important Cultural Property (juyo bunkazai), the first film to be so honoured.

Note: Originally published on The Bioscope 11 May 2010 and reproduced here with slight emendations. Almost inevitably, the film can now (2015) be found on YouTube, though not uploaded from an official source.